10th Grade Syllabus (2014 – 2015) Mr. Ross Abrams abramsr

advertisement

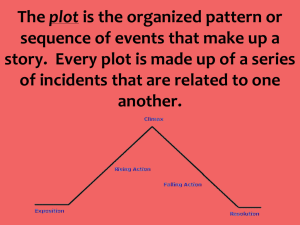

10th Grade Syllabus (2014 – 2015) abramsr@hohschools.org royalr@hohschools.org Mr. Ross Abrams Ms. Robyn Royal photo by Robert Frarck Year Overview: The Art of Reading and Writing Writing is easy. Reading is easy. We do both almost all the time and, for the most part, think little of them. When we scribble a shopping list, text message our parents to pick us up from “If I Stay” or “The November Man,” or scan the supermarket shelves for a box of our favorite sugar cereal, we engage in a rather complex set of mental and physical negotiations; however, we rarely stop to fully consider the choices we are making - should I use full sentences or fragments in this e-mail? Why are most of the cartoon characters on cereal boxes male? How should I tell my best friend I may have, sort of, kind of, gone out with her boyfriend without telling her? The purpose of this course is to make you more conscious readers and writers and to demonstrate how small language choices make big differences. We will share with you all we know about reading and writing as an art-form and encourage you to take risks in your perception and craft. We hope to create challenges that demand both effort and intellectual stretching. Think of yourself as language detectives, intent not on solving what a book or a sentence means, but on tracing the complicated, interesting paths that lead to your deductions. In many other academic classes, success may be measured by everyone in the classroom arriving at the same answer at the same time. Success in this class will look different. We find the most successful writing and reading prompts are those that inspire the greatest range of interpretation and complexity. We are interested in your unique voice, your unique angle, and what you can bring to the discussion that is new or provocative. What You Can Expect From Us • • • • • • • • • Challenging assignments – expect to be “optimally frustrated” Lots of care and attention as you struggle and learn Accessibility – you can meet with us before or after school most days. Don’t be shy – I’m happy to talk with you about anything related to the course (or music, or books…) Fair and equitable treatment Challenging class sessions Prompt return of papers and assignments Book Recommendations An open ear and an open mind A positive attitude What I Expect from You A “no-fear” attitude when it comes to challenges Respect for classmates, teacher, and the class materials Assignments handed in on time, all the time Consistent, punctual attendance and preparation for class Participation – contributing to class discussions, working well in groups, actively listening to others, reading, writing, and taking notes Effort and honesty About four hours of homework in a seven-day period An open ear and an open mind A positive attitude Homework Your time is precious. You spend seven hours a day in school – many of you play a sport or participate in extracurricular activities. Some of you have jobs and others of you are responsible for taking care of a younger sibling. You have passions outside of your academics – jazz on vinyl, community service, MRPG, dance, etc. You must know what Kanye West is twittering at 10PM. We will do our best to be respectful of your time by only giving assignments that we deem essential to continuing your growth in English. You have been blessed with a brain that is particularly elastic at this moment in time and we want to capitalize on that by pushing and challenging it but we also don’t want to see the circuits overloaded. You can expect somewhere around two hours of work during each week and an additional hour-and-a-half over the weekends. We are sticklers for time. If we ask you to work on an assignment for half-an-hour,we mean an honest half-an-hour (with facebook closed, cell phone on standby) but that also means we do not expect you to go beyond a half-an-hour, even if the assignment is not completed. Occasionally, you will find yourself particularly overwhelmed by work in other subjects or by other commitments. All we ask is that you seek me out prior to an assignment being due – in person, on the phone, or by e-mail – and we will do our best to work with you on figuring out an appropriate timeline for completion. When it comes to homework, we are on your side. Help! You might find it interesting to know that we are both currently enrolled in an advanced graduate programs, which means that while you are up at ten o’clock struggling with that impossible English paper, chances are, somewhere across town, we are doing exactly the same thing! One of the most valuable lessons we have learned from being students for over twenty years now is the importance of seeking out help from others – from our peers, teachers, and families. Often times, we just need a sounding board for our ideas or someone to ask the questions we may have missed. We are happy to spend as much time as you need talking through any of the assignments or requirements from this course. Our schedules can be pretty hectic but we will always find time to meet with you to work on whatever you need. Grading/Assessment We like reading student papers – no, really, we do! We enjoy writing comments in praise of beautiful turns of phrase, smart insights, and good humor. We also spend a good deal of time thinking about the specific writing choices that separate sophomoric writers from accomplished writers and will gladly give you constructive criticism to help you bridge that gap. Alas, we will also give you grades. We grade the work and not the student. We will assess your writing pieces on a very high standard for clarity, originality, consistency, and conciseness. An “A” or practitioner piece of writing will be a thing of perfection, good enough to end up in a local newspaper or magazine – it will be thoughtful, demonstrate an awareness of audience, and add something new to the conversation. We do not expect you to get A’s on your assignments at the beginning of the year; rather we expect you to slowly, through lots of hard work, to rise to the standards we have set. Expect most of our assessments (tests, papers, quizzes, discussions) to be “formative” rather than “summative.” What that means is that we are giving the assessment with the expectation that it will reveal concrete areas for growth – for you as a student and for us as teachers. “But wait!” you scream. “That’s not fair! In all my other classes, it does not take an act of Herculean intellect to receive a 98.” This is true, which is why we will “soften” the hard grading of papers with a series of “all or nothing grades.” These are assignments that you will receive an automatic “100” on just for turning them in. By combining “soft” and “hard” grades we hope to fairly measure your work as a high school sophomore but also give you a high standard for which to reach. Academic Integrity, Plagiarism and Collusion Policy Pundits have dubbed this the Information Age and with good cause. We are awash in information. Obscure literary theorists, once relegated to the upper echelons of elite university libraries can now be “googled” in mere seconds. Perhaps a better tag for our time would be the Age of Access. The unprecedented access we have to academic sources necessitates a consistent and transparent effort on the part of teachers and students to protect authorship. Abraham Lincoln once said that “books serve to show a man that those original thoughts of his aren’t new at all” (ironically, not the first time this sentiment has been expressed). However, the “willful appropriation of another’s ideas or expressions as your own” (Webster’s) also known as plagiarism, as well as “secret co-operation to defraud” known as collusion, come with severe penalties in the real world (fines, debarment, expulsion). In this class, collusion or plagiarism will be caught (We’re pretty good at this) and penalized – students will re-write work with us after school for half the grade. If you find yourself at the point of desperately needing to copy someone’s work both you and we are doing something wrong and it is imperative that you come see us immediately so we can work through the problem together. What You Need A notebook with plenty of lined paper for notes and in-class writing A school google account A folder capable of holding the tons of handouts I will give you If you prefer typing and have a laptop, you are welcome to bring it to class Our Classroom While you may not always have the choice of who you sit next to, or what book we will read next, it is you who will ultimately choose what kind of class we have this year. Your participation, feedback, and attitude in the classroom will set the tone and mood for our studies. We will rely on you to let us know of any concerns or questions you might have in regards to any aspect of this class. This should be a great year! ****************************************** What the Year Looks Like (for now) The curriculum for this course will bend, twist, and meld to fit the needs and interests of our class; attached is a list of the major foci for each marking period, along with the texts and assignments we may undertake. Marking Period One: The Art of Noticing; The Joy of Saying Something Texts: Caravaggio, Amerighi. David and Goliath Laux, Dorianne. The Book of Men Arbus, Diane. Boy with Toy Hand Grenade Schwartz, Ruth. “The Swan at Edgewater Park.” White, Victoria. “Elephant Grave” Komunyakka, Yusef. “We Never Know” Szymborska, Wislawa. “The End and the Beginning” Stafford, William. “Travelling Through the Dark” Bukowski, Charles. “The Black Birds are Rough Today” Major Assessments Poetry Archeology – Original Poems Art Lecture Independent Reading Responses Poetry Analytical Paper Goals: Students will… notice five kinds of details in a work of art utilize thin (factual) and thick (inferential) questions to spur analysis and exposition. differentiate between and use the three building blocks of essay writing: exposition, argument, and analysis. employ techniques for re-vising writing consider audience’s understanding and questions in their writing use powerful verbs for exposition incorporate non-restrictive elements, such as appositives, into the sentence structure analyze the effectiveness of word choices notice and analyze literary elements used in poetry keep an “archeology” journal to inform their own creative writing produce and revise writing for publication write organized speeches, keeping in mind audience employ techniques, such as eye contact, for effective public speaking use context to deepen, broaden, and complicate analysis and argument Maya Lin’s “Wave Hill” Poetry is just the evidence of life. If your life is burning well, poetry is just the ash. – Leonard Cohen Marking Period Two: One Equals Two; Finding Competing Meanings in a Work of Art Texts: Lahiri, Jhumpa. The Interpreter of Maladies Anderson. M.T. Feed Sophocles, Oedipus Rex Shaffer, Peter. Equus “Loving the Internet (Reuters) Kennedy, Pagan. “The Cyborg in Us All” Independent reading: 1,000 years Major Assessments Interpreter of Maladies comparison paper Harkness discussions “Inspired By” Transformation Film Comparison Paper A New World, exposition and argument Dialectics Goals: Students will… connect analysis of specific details to analysis of a work’s larger “projects.” create and evaluate competing theories/claims. utilize the theory of parsimony in evaluating analytical claims. effectively compare two works of art. employ a range of subordinate conjunctions. evaluate what can be quoted and what can be paraphrased from a work of art. In academic discussions, participate in more than one way. use verbal and physical cues to show engagement in academic discussion. notice five kinds of details in a work of art. (continued) utilize thin (factual) and thick (inferential) questions to spur analysis and exposition. (continued) differentiate between and use the three building blocks of essay writing: exposition, argument, and analysis. (continued) employ techniques for re-vising writing. (continued) consider audience’s understanding and questions in their writing. (continued) use powerful verbs for exposition incorporate nonrestrictive elements, such as appositives, into the sentence structure. (continued) analyze the effectiveness of word choices. (continued) produce and revise writing for publication (continued) use context to deepen, broaden, and complicate analysis and argument (continued) “It is always possible to argue against an interpretation, to confront interpretations, to arbitrate between them and to seek for an agreement, even if this agreement remains beyond our reach.” - Paul Ricoeur Marking Period Three: Close Reading of Literary Text Texts: Golding, William. The Lord of the Flies The Great Tragic Openings (Shakespeare) or excerpts from The Bible Erdrich, Louise. “The Red Corvette” Saunders, George. “Tenth of December” Alexie, Sherman. “Breaking and Entering” Dubois, W.E.B. “The Comet” Nelson, Antonya. “In the Land of Men” Major Assessments * Difficult Reading Quizzes * Creative Transformation * Drafted Short Story Goals: Students will… use S.L.I.D.E.R. conjunctions for transition. paraphrase deeply. integrate quotations in multiple ways. correctly identify, analyze and use the following literary elements: figurative language, narrative point-of-view, setting, conflict, imagery, and characterization. recognize and imitate stylistic choices made by an author. connect analysis of specific details to analysis of a work’s larger “projects.” (continued) create and evaluate competing theories/claims. (continued) utilize the theory of parsimony in evaluating analytical claims. (continued) effectively compare two works of art. (continued) employ a range of subordinate conjunctions. (continued) evaluate what can be quoted and what can be paraphrased from a work of art. (continued) In academic discussions, participate in more than one way. (continued) use verbal and physical cues to show engagement in academic discussion. (continued) notice five kinds of details in a work of art. (continued) utilize thin (factual) and thick (inferential) questions to spur analysis and exposition. (continued) differentiate between and use the three building blocks of essay writing: exposition, argument, and analysis. (continued) employ techniques for re-vising writing. (continued) consider audience’s understanding and questions in their writing. (continued) use powerful verbs for exposition incorporate nonrestrictive elements, such as appositives, into the sentence structure. (continued) analyze the effectiveness of word choices. (continued) produce and revise writing for publication (continued) use context to deepen, broaden, and complicate analysis and argument (continued) Marking Period Four: Writing the Right – Studies in Ethics Texts: LeGuin, Ursula. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” Plato, The Republic (excerpts) “Parable of the Prodigal Son” Kant, Immanuel. “The Categorical imperative” “Morality and the Brain.” Radiolab Book Club Reading Choices: The Bluest Eye (Toni Morrison), The Road (Cormac McCarthy), Macbeth (William Shakespeare), Tracks (Louise Erdrich), City of Thieves (David Benioff), and Slaughterhouse Five (Kurt Vonnegut) Philosophical essays by Don Marquis, Mary Anne Warren, Tibor Machan, Alastair Norcross, Louis Pojman, and Stephen Bright. Major Assessments: Evolving Argument Research Paper Book Club Presentation Final Speech Goals: Students will… organize extended arguments. use parallel structure to build transitions. introduce, paraphrase, and quote from academic sources. use S.L.I.D.E.R. conjunctions for transition. (continued) paraphrase deeply. (continued) integrate quotations in multiple ways. (continued) correctly identify, analyze and use the following literary elements: figurative language, narrative point-of-view, setting, conflict, imagery, and characterization. (continued) recognize and imitate stylistic choices made by an author. (continued) connect analysis of specific details to analysis of a work’s larger “projects.” (continued) create and evaluate competing theories/claims. (continued) utilize the theory of parsimony in evaluating analytical claims. (continued) effectively compare two works of art. (continued) employ a range of subordinate conjunctions. (continued) evaluate what can be quoted and what can be paraphrased from a work of art. (continued) In academic discussions, participate in more than one way. (continued) use verbal and physical cues to show engagement in academic discussion. (continued) notice five kinds of details in a work of art. (continued) utilize thin (factual) and thick (inferential) questions to spur analysis and exposition. (continued) differentiate between and use the three building blocks of essay writing: exposition, argument, and analysis. (continued) employ techniques for re-vising writing. (continued) consider audience’s understanding and questions in their writing. (continued) use powerful verbs for exposition incorporate nonrestrictive elements, such as appositives, into the sentence structure. (continued) analyze the effectiveness of word choices. (continued) use context to deepen, broaden, and complicate analysis and argument. (continued) write organized speeches, keeping in mind audience. (continued) employ techniques, such as eye contact, for effective public speaking. (continued)