Lesson Plan ()

advertisement

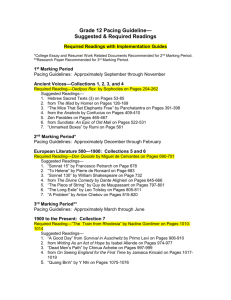

Juxtaposition Essays—Formulate juxtapositions of ideas, concepts, arguments, contradictions, quotes, or theoretical implications from five sets of readings during the semester. The schedule indicates the dates by which a minimum of these juxtapositions must have been completed. The specific requirements of this assignment in this syllabus packet, along with the grading rubric. (5 juxtapositions at 10 points each = 50 points). You get to choose which five weeks of the semester you will present on, but the instructor will solicit a distribution of presenters so that every week should have at least a few presenters. The juxtapositions will be presented as oral presentations toward the beginning of the class as a stimulus to conversation and debate. You are expected to treat these as oral presentations; thus, clarity and persuasiveness of presentation is taken into account. In other words, “wing it at your own risk!” [50 points] JUXTAPOSITION EXEMPLAR & TEMPLATE Name: Brian H. Spitzberg E-mail: spitz@mail.sdsu.edu COMM 610: Advanced Comm Theory Date: 09/11/2012 Jux #1 1st Claim(s)/Concept(s): Miller (1975) explicitly claims that the division of rhetorical and communication science is based on the questions asked, and not the methods they use. 2nd Claim(s)/Concept(s): Berger (1991) claims that a fundamental cause of the deficit of theories in the field of communication is the aversion to risk-taking in theoretical predictions. Juxtaposition(s): Asking questions doth not a discipline make! A question may be the beginning of a theory, but it is incapable of specifying the methodology by which it could be answered. The fundamental feature of “science” is not that it asks questions differently from rhetoric, but that it answers them differently. Rhetoric may address questions of “grand theory” and empirical nature (e.g., Fisher’s claim that some narratives are more likely to be effective [i.e., persuasive] than others, or Burke’s claim that scape-goating can effectively energize a rhetorical audience). The difference is that science does not hide behind historicism or ideographic presumptions regarding the generalizability of knowledge claims. Instead, science it makes predictions that run the risk of failure and provides a methodology for ascertaining success or failure, whereas rhetoric and humanities do not. Such falsifiable questions may indeed take different form than those in rhetoric or the humanities, but such a difference is meaningless unless the methods of falsification are presumed to permit the testing of such questions with an eye toward their truth-value or verisimilitude, which requires risk-taking. References (if any citations from non-syllabus sources): COMM 610 (Spring 2013): Advanced Communication Theory: p. 2 JUXTAPOSITION EXEMPLAR & TEMPLATE Name: Brian H. Spitzberg E-mail: spitz@mail.sdsu.edu COMM 610: Advanced Comm Theory Date: 09/11/2012 Jux #1 1st Claim(s)/Concept(s): O’Boyle and Aguinis (2012) demonstrate in several populations that outstanding “performance outcomes are attributable to a small group of elite performers” or superstars (p. 106). 2nd Claim(s)/Concept(s): Burke and Harrod (2005) compare positive and negative partner evaluations, and find that “the greater the discrepancy in terms of being either over- or underevaluated, the greater the likelihood that the person will leave the relationship through separation or divorce” (p. .371). Ehrlinger et al. (2008) produce evidence that “poor performers are overconfident in estimates of how well they performed relative to others because they have little insight into the quality of their own performance,” whereas “top performers’ mistakenly modest relative estimates were produced by erroneous impressions of both their own objective performance and that of their peers” (p. 117). Juxtaposition(s): Superstars are overly modest, whereas incompetents are overly optimistic, in their self-evaluation. The overevaluations, however, work to the detriment to the incompetents, whereas the modesty bias has little or no negative consequence for top performers and superstars. Indeed, modesty may be part of what sustains the positive evaluations that others would have of superstars, and unmerited narcissism or halo-bias may be part of what restricts the performance of underperformers, and help explain why most people are under-performers. Yet, the Burke and Harrod (2005) research suggests that these under- and over-performers all are likely to prefer partners who verify their self-perceptions. This calibration would mean that superstars prefer partners who affirm the superstar’s more modest achievement, whereas underperformers would prefer partners who confirm the under-performer’s inflated self-evaluation. Again, this would suggest that superstars are kept humble by their intimate relationships, whereas underperformers would function best intimately with partners who sustain the under-performer’s selfdeception, even though the effect would be to make that person less capable of performing well for lack of an ability to accurately perceive self’s ability and other’s estimations of that ability. The implication is a triangulated self-reinforcing tendency for superstars to get better in social evaluations both within and without their intimate relationships, whereas the less competent performers get increasingly stuck by failed relationships that fail in part because the incompetent persons promote and seek confirmation for their own biased and inaccurate self-evaluations. The possibility of this social amplification process is not recognized by O’Boyle and Aguinis (2012) or Ehrlinger et al. (2008), illustrating the importance of theorizing beyond the individual or dyadic unit of analysis. References (if any citations from non-syllabus sources): COMM 610 (Spring 2013): Advanced Communication Theory: p. 3 REASONED JUXTAPOSITION OF READINGS For the weeks specified, all students will be expected to produce a reasoned juxtaposition of some concept(s) from at least two of the readings for that seminar, and turn it into the professor. It is recommended both as a reading heuristic for students, as well as an indication of the level at which students are critically reading the assigned readings. The materials must fit on one page, and must derive at least in part from the readings for that day’s readings (and may include in addition materials from other readings in the course). The entire assignment must fit on a single sheet of paper, and have font no smaller than 10-point Arial, 10-point Calibri or 11-point Times Roman (1-inch margins). Exemplary student juxtapositions should serve as bases for student lines of questions and oral argument during class discussions throughout the semester. Juxtapositions will be graded on a simple scale as follows: Assessment Rubric Either no assignment is turned in on time, or the materials are either not logically interconnected, or represent the most surface extraction of meanings from the readings, indicating a shallow or hurried reading of the course materials. Points 0 1 Relevant concepts are mentioned but are defined in a shallow manner; linkages among concepts are loose or strained; implications lack credibility or import. 2 3 Relevant concepts are formulated and connected, but the links are somewhat obvious and lacking in depth of intellectual challenge. 4 5 At least one substantive juxtaposition is identified, leading to a contradiction, paradox, or theoretical principle. The result is a single reasonable claim that furthers the content of the readings considered individually, but integrates or suggests little else beyond this single concept. 6 7 The contradiction, paradox or theoretical principle is unfolded into several directions, but the import or implications are inconsistent in quality or implications are left without explication. 8 9 Multiple implications are derived from the juxtaposition(s) of concepts identified in the readings. The implications are extended into multiple directions of analysis or synthesis with other concepts identified in the course. 10