Submited paper

advertisement

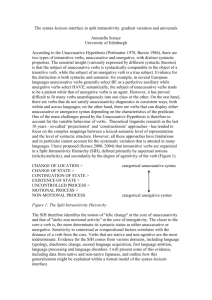

Acquiring the unaccusative/unergative distinction: evidence for syntax-driven approaches to lexicon-syntax interface We investigate the acquisition of the unaccusative/unergative distinction by a 3L1 child (S) with English, Italian and Scottish Gaelic. The literature claims that there are differences in the acquisition of unaccusativity cross-linguistically (e.g. Babyonyshev et al 2001, vs Snyder, Hyams and Chrisma (1995). No previous study has tried to see whether the acquisition of the distinction in a speaker of English and Italian shows evidence of cross-linguistic influence. Additionally the unaccusative/unergative distinction poses an interesting puzzle: if unaccusativity is semantically determined, unaccusatives are expected to be both stable and consistent across languages and within a language. This hypothesis is ideally tested in multilingual acquisition. The current study reports on three grammaticality judgment tasks. In English we tested perfect participles and resultatives, (1) and (2). In Italian auxiliary selection, (3). The results are in the table 1-3. The findings reveal that S has acquired the unergative/unaccusative distinction in both languages (with English results nearly at ceiling, while Italian results are not as robust). Interestingly, there is considerable overlap between the lexical verbs that S miscategorises in the two languages. The verbs fall into several semantic classes making a lexical semantic-driven analysis of error difficult to sustain. In contrast a Syntactic Bootstrapping approach (according to which a protracted period of overgeneralisation is to be expected, see Sorace 2004 and Borer 2004) can explain our data. The child has syntactic frames and inserts verbs into them giving rise to alternations which are ruled out in the adult language. What about the overlap? One of the crucial aspects of syntax-driven approaches to alternations is that meaning alone cannot drive computation and that meaning is a by-product of syntax. There is nothing intrinsic about the meaning of sleep that explains why it shouldn't be possible to use it in a causative frame. The fact that S makes mistakes with the same verbs in both English and Italian can then be viewed as confirmation of the fact that syntax is so prominent in the derivation of structure in one language to take over the way verbs are used in the other. 1. To get to granny’s cottage, red riding hood had to cross… the frozen lake. 2. *Dora screamed happy. 3. a. Biancaneve ha dormito tanto! Biancaneve is slept lots Table 1 English Results English Perfect Participle GJT English Resultatives GJT b. *Biancaneve é dormito tanto! Biancaneve has slept lots! Verb class Example Correct Judgment % Incorrect judgement % Unaccusative *Unergative The frozen lake *The shouted postman 75% 81% 25% 11% Fillers Unaccusative The storm appeared The glass smashed into pieces *Woody sang tired John drank his tea 100% 81% 0% 11% 91% 100% 9% 0% *Unergative Fillers Overa ll correc t% 82% 89% 86% Across tasks Table 2 Italian Results Italian Auxiliary Selection Verb class Example Unaccusative il vaso è rotto – the vase broke Il bambino ha riso – the baby laughed Unergative Alternating verbs Correct judgement % 58% Incorrect judgement % 42% 75% 25% 75% 25% Overall correct % 66.5% 75% Table 3 Wrongly Judged Verbs in English and Italian Language Mistakes Verb type Status English only Cook Change of state Unaccusative Dance Controlled motional unaffecting process Change of state Unergative Unergative Fall / Cadere Controlled non-motional unaffecting process Controlled non-motional unaffecting process Change of Location Appear / Apparire Change of State Unaccusative Freeze / Congelare Change of State Unaccusative Jump / Saltare Sorridere (Smile) Controlled motional process Controlled non-motional unaffecting process Controlled non-motional unaffecting process Change of Location verb Unergative (alternating) Unergative Slam Scream English Italian Italian only and Sleep / Dormire Cantare (Sing) Arrivare (Arrive) Unaccusative Unergative Unaccusative Unergative Unaccusative