Intractable Problems EJ Friedman Spring 2012

advertisement

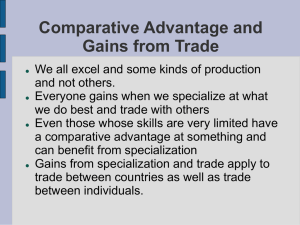

International Norms, Gendered Institutions, and Latin American Women’s Rights Paper Prepared for Workshop on Informal Institutions and Intractable Global Problems, Purdue University, April 16-17, 2012 Elisabeth Jay Friedman, Politics and Latin American Studies, University of San Francisco ejfriedman@usfca.edu Draft: not for citation This paper addresses the impact of international norms and formal and informal institutions on the achievement of women’s rights, with reference to Latin America. Since the 1990s, Latin America has become known as a region where women have made great strides in formal politics. Candidate quotas for women on party lists have resulted in the second highest regional percentage of women’s representation in national parliaments. Women have been elected president in six countries and, in the 2012 July Mexican elections, possibly will become chief executive of a seventh. But at the same time, many long-sought feminist demands, such as full reproductive rights and the implementation of anti-violence statutes, remain unfulfilled. How are we to understand these paradoxical developments, which simultaneously uphold and challenge notions of global movement towards women’s empowerment? Although a comprehensive answer to this question is complex and varies from country to country, this paper focuses on a key dynamic: the interaction between international norms and national “gender regimes,” or the ways in which formal and informal institutions are influenced by gender relations. As shown below, tracing this interaction adds to existing explanations of norms transmission in three ways. First, levels of analysis are not neatly bifurcated in the actual transmission process. Second, norms transmission must be sequenced in order to make regional results intelligible. Third, gender and class relations help to explain why some rights are established before others. 1 In exploring the dynamic of norms transmission, this work also contributes to the understanding of how informal institutions in particular are implicated in the “intractable” – or at least, deeply embedded – global problem of gender inequality. Throughout the process of norms transmission, actors use informal institutions to both reinforce and challenge gender relations. And as they do so, they demonstrate that these institutions are “multiscalar,” drawing together actors, resources, and ideas from the local to the global. The paper is organized as follows. It begins by reviewing the debate over whether international or national factors are more salient for the transmission of women’s rights norms, using a feminist institutionalist perspective, which understands both formal and informal political institutions to be permeated by gender relations, to illuminate national contexts. It then argues that an “imbricated” or “multiscalar” analysis, as well as a sequenced version of norm transmission, is needed to explain the situation of distinct women’s rights claims in Latin America. This theoretical context is then followed by a three-part empirical analysis that traces the establishment, diffusion, and implementation of Latin American women’s rights, using examples of political, social, and economic rights ranging from candidate gender quotas to conditional cash transfer programs. At this stage this analysis offers more of a framework for understanding than a comprehensive set of cases, but points to what are hopefully fruitful directions for exploring women’s rights achievement in Latin America and elsewhere. Explaining Women’s Rights: International Norms and National Gender Regimes Analysts differ in their approach to understanding whether the problem of gender inequality is ameliorated by the transmission of international norms. Some scholars have argued that women’s rights have begun to follow a norm “cascade.” This happens after a “tipping 2 point” has been reached, when sufficient states adopt international ideas such that other states will adopt the norm regardless of the extent of external support or domestic pressure (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). But generally, this cascade only happens when the norm is institutionalized “in specific sets of international rules and organizations” (Ibid., 900). At that point, states will be beholden to a “logic of appropriateness,” emulating policy “that has been defined as integral to a good nation-state identity” (Wotipka and Ramirez 2008, 304). The evidence of the impact of international norms on the achievement of women’s rights is strong when considering the basic building block of political participation, suffrage. According to Francisco Ramirez, Yasemin Soysal, and Suzanne Shanahan (1997), after 1930 a “world model of political citizenship” that included women’s enfranchisement became the most important factor in determining the expansion of suffrage. More evidence is offered with respect to the adoption of the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the international women’s rights treaty adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1979. The development of a significant international infrastructure at the international level – now that “the United Nations system is replete with programs, specialized agencies, regional commissions, and international instruments aimed at addressing a plethora of women’s issues” – has been influential in convincing states to adopt the women’s treaty (Wotipka and Ramirez 2008, 304). Dongxiao Liu, however, shows how international norms, bundled in documents such as the Beijing Platform for Action produced by the Fourth World Conference on Women (1995), are not on transmission belts to the national/local context. Instead, national movements working in and with national contexts very much determine their usefulness: “Movement responses to 3 international agendas involve context-dependent meaning-making processes” (Liu 2006, 930). In other words, these norms become one of a host of different factors contributing to the struggles of feminist movements and the success (or failure) of women’s rights claims. Jocelyn Viterna and Kathleen Fallon’s work on women during democratization also points to the agency of women’s movements in framing international ideas within national contexts, including their own histories of activism: “Political parties are a necessary vehicle for carrying women’s demands to the state, but we find that the type of vehicle (i.e., party ideology) matters less than how well the vehicle is driven by women’s mobilizations” (Viterna and Fallon 2008, 685). Mala Htun and Laurel Weldon also insist in variation on state “vulnerability to international pressure,” that depends on how much their legitimacy is questioned by external actors: “In countries that need to please global audiences, international advocacy networks and agreements have more powerful effects” (2010, 212). Sarah Bush’s (2011) study of quota adoption echoes this finding, but also finds that concrete assistance is at stake where countries are subject to “democracy establishment” for the reestablishment of their polities (as well as where they are not, such as the US). These findings evoke the importance of integrating of the national context in any analysis of women’s rights achievement, a process that shows the importance of differentiating among rights, rather than treating them as a “bundle” that will be achieved simultaneously. Htun (2003) and Htun and Weldon (2010) insist that a disaggregation of rights is crucial to understanding why there is significant variation in their advancement. 4 The need to incorporate national contexts is revealed by studies of rights achievement such as those mentioned above. Analysts focus on distinct elements. There are what could be grouped as “background factors,” including national histories and configurations of distinct relations of power including but certainly not limited to gender relations. These are mediated by “contingent factors” such as regime change, electoral politics, and dynamics of economic reform or recession. Then there are factors drawn from social movement theory, including women’s movement history, its leadership, membership, and organizational form. These factors then interact with the institutional edifice. Following Michelle Beyeler and Claire Annesley (2011, 81), I find institutions to be enduring “systems of rules that can be both formal, like written norms, procedures, laws, and contracts, and informal, like norms of behavior, codes of conduct, and conventions.” These informal institutions are “created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels” (Helmke and Levitsky 2006:5). Both formal and informal institutions are permeated by social relations of power. Of particular interest to the subject at hand, feminist institutionalists have explored how they are gendered, which is to say that gender relations are embedded within them such that they are “structured by gendered assumptions and ‘dispositions’ … and produce outcomes including polices, legislation and rulings that are influenced by gender norms. In turn, these outcomes help to re/produce broader social and political gender expectations” (Mackay, Kenney and Chappell 2010, 580). Examples of the formal institutional frameworks that are gendered include “state architecture,” (Franceschet 2011) such as the constitutional framework and vertical and horizontal organization (federalism, executive, judicial, legislative, etc.). Political society, 5 including its rules and party system are also gendered, as is civil society, including economic, social and political organization (Friedman 2000, 35-42). While gendering has predominately resulted in the marginalization of women and their issues, there is evidence that women inside state institutions “can exploit institutional openings and even re-orient institutions and practices to feminist goals” (Franceschet 2011, 62). Crossparty women’s committees in legislatures and national women’s machinery have been effective institutional interventions (Phillips and Cole 2009), although certainly no panacea for the dominant gender implications of institutional architecture. For example, the national women’s machinery is often subordinated to other executive branch institutions, or helps to re-inscribe traditional gender configurations if focused on “women and the family.” In understanding the gendering of these institutions, a focus on their design and operation is crucial, but their interpolation with women’s rights claims also requires considering the gendering of actors inside of them. Although male dominance of political decisionmaking is still the norm, it has been challenged due to the diffusion of candidate gender quotas as well as the rising number of women in the executive branch, including the chief executive. “Femocrats,” or female bureaucrats who are focused on gendered policy arenas, are also relevant actors. One additional area to take into account is that of political discourse. Jane Jenson’s (1987) concept of the universe of political discourse, comparable to Gramscian hegemony, delimits “the acceptable actors, actions, and subjects of politics, which are determined through ideological interpretation of basic social arrangements” (Friedman 2000, 25). It thus helps to determine not only what is political but who can be a political actor, and is inevitably marked by gendered assumptions (Friedman 2000, 32-35). 6 Besides formal institutions and discourses, informal institutions, including coalition dynamics and informal political networks, have gendered outcomes (Franceschet 2011, Beyeler and Annesley 2011). Particularisms of various kinds reveal gendered bases: in patron-client networks, the gender of the patron – and that of the client – is key to understanding how that relationship works. “Old boys” political networks continue to be a key mechanism for political advancement, and such networks are often based in areas traditionally reserved for men. The informal – but reliable – “veto players” in economic, social, and political “games,” are the real “gatekeepers” of decision-making. Because their interactions are informal they may be harder to change than formal rules with clearly distinct outcomes for men and women, and their impact may extend far beyond a particular set of interactions. Women who refuse to play by, essentially, men’s rules may jeopardize their political careers, and thus often have to learn how. Much of the work that has been done on the gendering of institutions has focused on the formal side, or examined how informal institutions are biased against women’s agency or their issues. But informal institutional arrangements have been used to women’s benefit. A central example of this is what Anne Maria Holli (2008, 169) calls “women’s co-operative constellations,” that is “any kind of actual co-operation initiated or accomplished by one or several groups of women in a policy process to further their aims or achieve goals perceived as important to them.” Various scholars have used such constellations to describe the cooperation among women’s movements, other non-governmental, and governmental actors – variously including feminist professionals in academia and elsewhere, female party militants, and women in executive and legislative positions (including “femocrats”), and feminist professionals (Vargas and Wieringa 1998, Woodward 2003). Evidence of such arrangements is implicit in findings such as Laurel Weldon’s (2002, 1170) conclusion that “strong, independent women’s 7 movements and effective women’s bureaus interact to provide an effective mode of substantive representation for women (1170). Lynne Phillips and Sally Cole (2009, 199) also find that “there is fluidity between the women's movements and the government due to informal networks of friendship and feminists' previous experiences of working together on specific campaigns. This fluidity contributes to multilayered translations of women's experiences.” These more flexible arrangements can be a response to exclusionary formal institutions, such as maledominated party structures or bureaucracies, and/or informal institutions, such as maledominated iron triangles or clientelistic networks. Although different scholars emphasize particular actors, the constellation itself can be seen as an informal institution used to further women’s rights claims. I have used the idea of a “conjunctural coalition” for much the same purpose, that is to describe how women operating across political arenas – executive, legislative, and civil society – have come together to promote issues of common concern (Friedman 2000, 51, 284-285). Although there are more formally organized examples of this (Holli (2008, 178) references an established network of female party militants and some NGOs in Finland), they often operate without formal rules or structure. What makes such a coalition an informal institution is that the actors involved will repeatedly engage with each other, often using similar repertoires of action, when the need arises. Achieving Women’s Rights in Latin America: Imbricated Analysis and Sequenced Norm Transmission Evidence from the Latin American region nuances more global arguments about norms transmission. Turning to regional and national examples reveal that while we might separate our levels of analysis for the sake of, if not parsimony, given the many elements laid out above, then 8 possibly clarity, in practice these analytics are so intertwined as to be braided like the Argentine quota provisions (which hold that women have to be integrated into winnable positions on party lists, rather than left for the unlikely bottom slots) that have resulted in one of the highest representation of women in any national parliament. The factors taken into account when considering women’s rights – the context, the actors, the discourse, and the institutions – shows the fact of “imbricated analysis.” As Janet Conway argues with respect to the World Women’s March (2008), local and national actors who have contributed to international norm development are not free-floating “transnational actors”: they come from somewhere. Likewise, when local and national actors use “transnational” discourses they construct their location by “practicing politics as multiple scales” (225). The kinds of cooperative constellations that have helped Latin American women advocate for their rights from national states have incorporated actors at the regional level, working in entities such as the OAS, and NGO networks such as the Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network. Many of those actors come from distinct national experiences, and return to them when their regional work is concluded. The movement of individual advocates among positions within informal coalitions can also strengthen them, as allies rotate. Another finding that emerges from the study of this particular region is that the process of norm diffusion has to be sequenced in order to be intelligible (Friedman 2009). Establishing international norms involves different institutions, discourses, and actors than those involved in diffusing them at the national level. Implementing these norms may depend upon yet a different set. And over the entirety of the process the norm itself may be transformed. 9 The conceptualization of women’s rights claims in Latin America used below is inspired by Htun and Weldon’s typology that differentiates among “sex equality policies.” They argue that these policies can be distinguished by two central principles: 1) whether they focus primarily on ameliorating women’s gender or class status and 2) the extent to which they challenge “religious doctrine or codified cultural traditions.” (2010, 209). Below, I disaggregate women’s rights by the extent to which they challenge gender relations – a somewhat broader category than their second one – and the extent to which they cross-cut or reinforce class divisions. Although this latter distinction could be seen as the same as Htun and Weldon – “cross-cutting” class divisions among women is the same as ameliorating inequalities based on gender – I seek to draw attention to the reality that some policies reinforce women’s class interests, a central dilemma in Latin American women’s organizing. Establishing Women’s Rights This paper addresses political, social, and economic rights by focusing on four different contemporary policies: candidate gender quotas as a proxy for political rights; the right to have a life free of violence and reproductive rights, specifically abortion, as proxies for social rights; and the anti-poverty policy Conditional Cash Transfers as a proxy for economic rights. As shown in the figure below, at the point of establishing these rights as international norms, three have been conceptualized as both cross-cutting class differences and challenging gender relations: women from all classes can theoretically benefit from positive action at the highest levels of governance, gendered anti-violence statutes, and abortion decriminalization. Antipoverty policies that address the feminization of poverty are empowering to women, but focused on the lowest class. This section briefly reviews how all rights claims have benefitted from international, and sometimes regional, norms. 10 Establishing Women’s Rights Norms Class Relations vs. Gender Relations Cross-Cutting Reinforcing Challenging Quotas Abortion Violence Against Women Anti-Poverty (CCT) Not Challenging Since 1979, CEDAW has justified the kind of “temporary special measures” (art. 4, para 1) designed to promote equality between women and men of which quota legislation is perhaps the most well-known example. This message was reinforced by the CEDAW Committee’s General Recommendation #25, issued at the end of the 1990s, which sought to clarify the use of this article. Establishing Quotas CEDAW: Article 4, paragraph 1 Adoption by States parties of temporary special measures aimed at accelerating de facto equality between men and women shall not be considered discrimination as defined in the present Convention, but shall in no way entail as a consequence the maintenance of unequal or separate standards; these measures shall be discontinued when the objectives of equality of opportunity and treatment have been achieved. 11 The Beijing Platform for Action, agreed to by governments meeting at the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women, also promotes quota policies in its objective “to substantially increase the number of women” in government (Strategic objective G.1). Even prior to Beijing, some Latin American countries were taking action: Argentina adopted quotas in 1991. But the importance of international agreements is clearly stated by regional analyst Jacqueline Peschard (2003, 21): “[i]t was not until after the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 that the region would embrace” quota legislation. Establishing Quotas Beijing Platform for Action, Strategic objective G.1. Take measures to ensure women's equal access to and full participation in power structures and decision-making Actions to be taken by Governments: Commit themselves to establishing the goal of gender balance in governmental bodies and committees, as well as in public administrative entities, and in the judiciary, including, inter alia, setting specific targets and implementing measures to substantially increase the number of women with a view to achieving equal representation of women and men, if necessary through positive action, in all governmental and public administration positions. Turning to reproductive rights, the Cairo Programme of Action, which also emerged from a UN Conference process – on Population and Development (1994) – establishes women and men’s right to reproductive health and references abortion as “a major public health concern” (article 8.25). The inclusion of this controversial framing was made possible by actions taken to build coalitions among women’s health and population control advocates prior to the conference 12 (McIntosh and Finkle 1995, Friedman 2003) and laid the groundwork for a shift in understanding elsewhere. In Latin America it inspired an unprecedented public debate on the topic of abortion, which moved the issue up on the political agenda and changed the terms of the debate. The emphasis shifted from moral absolutes to the right to safe abortion and the health consequences of illegal abortions and the lack of emergency contraception, evident in the region’s maternal mortality and morbidity rates, which were not only high but on the rise…Thus abortion ceased to be a taboo subject. (Reutersward et al. 2011, 807) Establishing Reproductive Rights Norms Cairo Programme of Action Article 7.2. …Reproductive health … implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so. Implicit in this last condition are the right of men and women to be informed and to have access to safe, effective, affordable and acceptable methods of family planning of their choice, as well as other methods of their choice for regulation of fertility which are not against the law, and the right of access to appropriate health-care services that will enable women to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth and provide couples with the best chance of having a healthy infant. Article 8.25: …All Governments and relevant intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations are urged to strengthen their commitment to women's health, to deal with the health impact of unsafe abortion as a major public health concern and to reduce the recourse to abortion through expanded and improved family planning services. Prevention of unwanted pregnancies must always be given the highest priority and all attempts should be made to eliminate the need for abortion. Women who have unwanted pregnancies should have ready access to reliable information and compassionate counseling. Any measures or changes related to abortion within the health system can only be determined at the national or local level according to the national legislative process. In circumstances in which abortion is not against the law, such abortion should be safe…. Establishing an international norm against violence against women was predicated in many ways by regional framing and mobilization. Latin American activists’ experiences of human rights suppression put them at the forefront of the anti-violence against women movement that developed over the course of the 1980s; they were central in the organizing that 13 put women’s human rights at the forefront of the human rights agenda. As an important symbol, November 25th, the international day against violence against women, was first established at a Latin American feminist meeting in 1981, to commemorate the anniversary of the deaths of the Miraval sisters who fought against dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. Latin American feminists also took part in the global organizing towards the Vienna UN Human Rights Conference (Friedman 1995). As this organizing took off, international organizations responded. Although violence against women was not explicitly dealt with in CEDAW, in 1992 the committee issued General Recommendation #19 interpreting aspects of the Convention as speaking to the issue of violence. At the UN Human Rights Meeting in 1993 the final document “mainstreamed” women’s human rights, including a section devoted to “the equal status and human rights of women” that established violence against women and girls as a violation of their human rights. But the major regional accomplishment, product of a profoundly regional process, was the adoption of the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women (often referred to as Belém do Pará after the location where it was adopted by the OAS). A regional organization – the Inter-American Commission on Women (IACW) – despite its marginal status within the often dysfunctional OAS system, has strategically marked off areas for concern from time to time, and did so in this case. Responding to the actions of feminists and women’s rights advocates across the region and their recognition of violence against women as a human rights violation, the IACW developed first international treaty informed by a feminist perspective that recognizes gender inequality and the many ways violence against women is manifest in society – and, similar to other human rights violations, holds the state responsible for preventing it (Friedman 2009). 14 Establishing Anti-VAW Norm Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women “Convention of Belem do Para” Article 1: …violence against women shall be understood as any act or conduct, based on gender, which causes death or physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, whether in the public or the private sphere. Article 2: Violence against women shall be understood to include physical, sexual and psychological violence: a. that occurs within the family or domestic unit or within any other interpersonal relationship, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the woman, including, among others, rape, battery and sexual abuse; b. that occurs in the community and is perpetrated by any person, including, among others, rape, sexual abuse, torture, trafficking in persons, forced prostitution, kidnapping and sexual harassment in the workplace, as well as in educational institutions, health facilities or any other place; and c. that is perpetrated or condoned by the state or its agents regardless of where it occurs. Article 3: Every woman has the right to be free from violence in both the public and private spheres. In terms of poverty alleviation, the Beijing Platform for Action recognized that development policies had gendered outcomes, and as a result, called for an assessment of and response to the impact of development on poor women. Responses included focusing on safety net and other support systems for women living in poverty; addressing women’s unemployment; supporting female-headed households, and insuring poor women’s access to food. 15 The establishment of these rights claims through international and/or regional declaration locates all of them as challenging established gender relations, and most, as cross-cutting class divisions. Although this achievement depended on actions within formal international and regional institutions, informal co-operative constellations were also fundamental. Throughout the conference processes of the 1990s, a “Women’s Caucus” operated, linking ideas, actors, and repertoires from conference to conference and coordinating actions through thematic task forces. This collective effort enabled advocates to affect international documents as they were developed over the two-year negotiating process preceding the conferences themselves. This collective presentation of women’s concerns was an important improvement over previous efforts, where individual NGOs presented position papers and lobbied individual delegates. Moreover, the Caucus assembled ‘‘precedent setting’’ information from previous UN documents to support advocates’ lobbying positions, thereby showing their positions to be ‘‘built on accepted norms within the UN, not new rights’’ (Clark et al., 1998, p. 15). This was a clear effort to mainstream the women’s rights message while countering objections to it. (Friedman 2003). Diffusing Women’s Rights Many advocates involved in transnational organizing were inspired to continue their collaborative efforts as they scaled down to national contexts, still supported by the networks from the conference processes. But taking internationally agreed upon language into national contexts, the second step in the transmission process, had varied outcomes. As shown in the figure below, the diffusion of international norms, filtered by national decision-makers working through formal and informal institutions, resulted in two sets of rights claims moving away from their initial challenge to relations of power. 16 Diffusing Women’s Rights Norms Class Relations Cross-Cutting vs. Gender Relations Reinforcing Challenging Anti-Poverty (CCT) Quotas Not Challenging Violence Against Women Abortion Quota diffusion was the most successful. Since the 1990s, nearly every country in the region adopted quotas ranging from 20-40% of candidate positions on party lists, with 13 established through legislative statute and another four through voluntarily party adoption. Country Quota Type(s) Argentina Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties Bolivia Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties Brazil Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Chile Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties (20-40%) Colombia Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level 17 Costa Rica Dominican Republic Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (40%) Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (33%) Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Ecuador Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (50%) Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level El Salvador Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties (35%) Guatemala Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties (30-40%) Honduras Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Mexico Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (40%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties Nicaragua Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties (30-40%) Panama Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Paraguay Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (20%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties Peru Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Uruguay Legislated quotas for the Single/Lower House (30%) Legislated quotas for the Upper House Legislated quotas at the Sub-national level Voluntary quotas adopted by political parties (International IDEA) Sarah Bush (2011) finds that, although external pressure on “democratizing” states was important for quota adoption in many countries, the region of Latin America is an outlier. Since the norm was still in its “infancy” during democratization processes in this region, she attributes its diffusion – mainly in the mid-1990s – to a domestic “demand.” The actions of women both outside and inside of the state were crucial for quota adoption, often based on a demand for the extension of democracy. Quota advocates organized at a very propitious moment; in the 1990s 18 Latin American governments were eager to adopt measures seen as legitimating their stilldeveloping democracies. Male leaders – even those not known for their democratic impulses, such as Carlos Menem of Argentina – took it on as such. The quota story, however, is not exclusively one of national action. European advocates from social democratic and socialist parties shared their experiences with their Latin American counterparts (Krook 2009, 166-167). In turn, regional diffusion often happened through face-toface encounters in places such as the Andean Parliament’s Women’s Caucus. Abortion offers a very different picture. This right, admittedly heavily contested internationally, has not been diffused at the regional level. Six countries ban in all circumstances, and all but Cuba restrict it (see figure below). Honduras recently banned emergency contraception as an abortifacient. Mexico City’s 2007 policy, which allowed for abortions to be performed in the first trimester, was immediately met with backlash so severe that over half of Mexican state constitutions now protect life from the moment of conception in. This norm is hotly contested in Latin America because it clashes with many aspects of national gender regimes, particularly the various ways that Catholic, and, increasingly, evangelical church hierarchies, influence individual politicians and political institutions (Richardson and Birn, 2011, 188-189). Advocates also face impediments in the form of informal institutions. Susan Franceschet (2011) argues that the informal institution of consensusseeking/conflict avoidance in Chilean politics restricts even self-identified feminist legislators from stronger action on feminist issues such as abortion. 19 Diffusing Reproductive Rights Norm Abortion illegal under all circumstances Chile, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua Exception if women’s life/health at risk Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Some Mexican States, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay Exception if pregnancy due to rape Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Uruguay Abortion legal Mexico City (first trimester) Cuba (first trimester or if health risk) Despite its near prohibition across the region, this policy reinforces class differences. As Emma Richardson and Anne-Emanuelle Birn (2011, 189) note, there is an “escape valve” in that middle class and elite women can often pay for illegal, yet safe abortions or travel to where they are legal, whereas poor and particularly poor indigenous or Afro-descent women have to resort to more dangerous illegal methods. These kinds of class differences are also evident in other reproductive health arenas. Christina Ewig (2006, 646) has shown how Peru “hijacked” international norms in its human-rights violating sterilization campaign: Sterilization campaigns especially targeted poor, uneducated, indigenous women who had little access to artificial contraception and who were easily deceived by staff members seeking to fulfill quotas or receive financial rewards. Not only did these conditions militate against genuinely voluntary and informed consent in reproductive health 20 services, but they reflected the class and racial biases of the Peruvian elite, from whom policymakers were drawn. Thus, while in theory reproductive rights are a cross-cutting issue for women, class (and ethnic) privilege mediates against them being experienced as such in practice. The translation of the clearly feminist regional norm against violence against women into national legislation reveals a more complex picture than might be observed at first glance, where 18 countries have adopted some form of legislation on domestic violence. Diffusing Anti-VAW Norm (Friedman 2009) 21 Across the region, there has been an astonishing norm cascade – but of a different norm than was intended by the regional treaty. As legislators tackled this norm, they most often gave it a spin that matched Catholic understanding of men and women’s complementary roles in the family. In law after law, the family was seen as the unit to protect – often mediation was offered as the solution to violence – and the problem of violence against women outside of the family neglected (Friedman 2009). Here again the power of gendered institutions is strongly evident. In Chile, feminist legislators initially constructed a bill that focused on the abuse of women by their partners. But the Christian Democrat Party, the dominant partner in the national coalition government, sought to placate the Catholic Church. They altered the bill so that it no longer took into account gender inequality inside the home, but instead referred more generally to domestic violence. As happened with abortion, women on the left responded to the demands of coalition politics by moderating their demands (Franceschet 2011, Friedman 2009, 364-365). The adoption of Conditional Cash Transfer policies, this paper’s proxy for economic rights, has also been widespread across the region. CCTs provide poor families with a regular cash payment on the condition that they meet certain health and education requirements for their children, such as medical checkups, vaccinations, and regular school attendance. Initiated in Brazil (1995) and Mexico (1997), by 2008 CCTs were adopted by nearly every Latin American country. They have been successful at their goals of reducing extreme poverty as well as meeting health and education targets (Johannsen et al. 2008, Molyneux and Thompson 2011). 22 Inception of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs in Latin America (95-08) (Johannsen et al. 2008) The transfer of cash most often goes to mothers, due to their social roles: “Making mothers central to the programme is understood by most commentators to be key to its success, as women can generally be relied upon to fulfill their responsibilities to their children and to manage the spending of the stipend in accordance with children’s needs” (Molyneux and Thompson 2011, 10). Not only children, but mothers themselves are assumed to benefit from this arrangement, in terms of their social status, autonomy, self-esteem, and domestic negotiating power. Some programmes include beneficiaries in management, or provide other opportunities to expand their civic engagement. Taken as a whole, the CCT experience is posited as “empowering” women (Molyneux and Thompson 2011, 10). 23 Implementing Women’s Rights In the third part of the norms transmission sequence, the implementation of laws and policies, there is movement back towards challenging gender relations. But social relations of power continue to have an impact on how rights are realized. Implementing Women’s Rights Norms Class Relations vs. Gender Relations Cross-Cutting Reinforcing Challenging Violence Against Women Abortion Quotas Not Challenging Anti-Poverty (CCT) While quotas continue to be the clearest success story, they are limited in two aspects. In terms of the fulfillment of the quotas, evidence (see below) shows considerable variation, from Argentina exceeding its quota of 30% with nearly 40% of lower house seats held by women, to Brazil and Panama not even coming close to fulfilling their 30% quotas with their poor showing of under 9% of lower house seats held by women. In 2009 Mark Jones found that in more than two thirds of the 29 legislatures with quotas that he examined (including sub-national legislatures), women accounted for less than 20% of the legislators, and in one quarter of the legislatures women represented less than 10% of the body’s membership. The reasons for this vary, but a key factor seems to be institutional design: in some systems, such design has permitted men to continue to dominate the party lists. 24 Implementing Quotas Implementing Quotas International IDEA 25 Advocates have certainly turned to their own legal systems when problems with quota implementation occur, but supporters have also sought recourse for quota implementation at the regional level, turning to institutions that have shown themselves open to promoting women’s rights. An Argentine woman filed the first quota petition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) as early as 1994, accusing a major party of not fulfilling the placement mandate for a provincial list of national parliamentary candidates. In 2001, the IACHR brokered a so-called “friendly settlement” in which the Argentine Executive agreed to issue a decree reinforcing quota legislation; this settlement also established the famous “braid” resulting in the nearly 40% we see today. As with the development of Belém do Pará, regional action on political rights has also included norm-building. At the urging of the IACW, the IACHR issued a set of “considerations” in its 1999 Annual Report finding that quotas compatible with regional HR treaty, the American Convention on Human Rights, and, as such, could be required to achieve substantive equality of opportunity (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 1999). Implementing Quotas IACHR Friendly Settlement, CASE 11.307, MARÍA MERCIADRI DE MORINI , ARGENTINA The President of the Argentine Nation Decrees: ARTICLE 1 - Article 60 of the National Electoral Code, as replaced by Law Nº 24.012, shall apply to all elective offices for deputy and senator to the National Congress and members of a National Constituent Assembly. ARTICLE 2 - The THIRTY PERCENT (30%) of the offices that are to be filled by women, as Law Nº 24.012 prescribes, is the minimum percentage. ARTICLE 5 - When ONE(1), TWO(2) or more seats are up for re-election, the calculation shall always be done starting with the first spot and the list shall have at least ONE(1) woman for every TWO(2) men in order to meet the minimum percentage required under Law Nº 24.012. Until the THIRTY PERCENT (30%) quota required under Law Nº 24.012 has been met, no three consecutive slots may be filled by persons of the same sex. Whatever the case, affirmative action measures shall be the preferred course, so that men and women truly have equal opportunity to seek elective office. IACHR Considerations 26 However, the women who are able to access power through quotas have done so by engaging in a gendered informal institution – candidate selection – that has resulted in little variation in representation beyond the not inconsiderable fact of gender inclusion. Leslie Schwindt-Bayer (2011, 2) shows that “female legislators in Latin America today are more similar than different from men in their backgrounds, paths to power, and political ambition. Women who win legislative office in Latin America do so by playing the traditional, male-defined, political game.” In general, both men and women are middle aged, and the vast majority are married (though fewer women in all three countries are married than men), have children, have received college or advanced degrees, emerge from traditional career paths of law, business, and the public sector, have prior political experience, and aspire to reelection and/or higher political office. Women do not appear to bring diverse social backgrounds, experiences, or different levels of political ambition to the legislative arenas of these countries, nor have they “feminized” the legislative arena in terms of backgrounds, experience, or political outlooks. As Chaney (1979, 110) noted 30 years ago: “[A]lmost always the ‘required’ elite social background and demographic characteristics must be possessed if a woman is to achieve a political leadership position, at least in formal political structures.” (Schwindt-Bayer 2011, 25). This “ ‘required’ elite social background” results in quotas continuing to privilege women of a particular class in their realization, although due to the political developments of particular national contexts, such as Bolivia, class variation has been more pronounced. Although the ability of women to obtain legal abortion remains tightly constricted across the region, there is national and multiscalar action going forward on this issue as well. 27 Nationally, judicial institutions seems to be protecting women’s limited rights in this area – albeit inconsistently. In 2006 the Colombian Constitutional Court lifted the previous ban on abortions, permitting the procedure in the case of rape, foetus malformation or if pregnancy posed a serious threat to the woman’s health. In 2007, Mexico’s Supreme Court found Mexico City’s abortion policy to be constitutional – but in 2011, it did not vote to strike down the state constitutional provisions effectively banning abortions. In 2012 the Argentine Supreme Court also insisted that women be able to get abortions under stated exceptions without having to get permission from a judge (the case beforehand). The Inter-American institutions have become increasingly active on this subject. The IACHR has brokered friendly settlements about pregnancy discrimination (Chile), sterilization (Peru), and abortion after rape (Mexico); the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which takes up cases that cannot be resolved through Commission action, is currently considering the right of Costa Ricans to access invitro fertilization, banned in that country. The regional action on reproductive rights corresponds to a search for receptive institutional arenas by feminist advocates working through the informal institution of a multi-scalar constellation, active at national level as well through regional networks such as CLADEM, which focuses on women’s legal rights, the September 28th Latin American and Caribbean Campaign for the Decriminalization of Abortion, and the Latin American and Caribbean Women’s Health Network. 28 Implementing Reproductive Rights IACHR Friendly Settlement, PETITION 161-02, PAULINA DEL CARMEN RAMÍREZ JACINTO, MEXICO The Mexican State, through the Health Secretariat, agrees to: …3. Draw up and deliver a circular from the federal Health Secretariat to the state health services and other sector agencies, in order to strengthen their commitment toward ending violations of the right of women to the legal termination of a pregnancy, to be sent out no later than the second half of March 2006. 4. Through the National Center for Gender Equality and Reproductive Health, conduct a review of books, indexed scientific articles, postgraduate theses, and documented governmental and civil society reports dealing with abortion in Mexico, in order to prepare an analysis of the information that exists and detect shortcomings in that information, to be delivered to the petitioners in November 2006. As part of the agreement, the Government of the State of Baja California is making this public statement, acknowledging that the absence of an appropriate body of regulations concerning abortion resulted in the violation of Paulina del Carmen Ramírez Jacinto’s human rights. +IACHR Friendly Settlement, Peru’s sterilization campaign; IACourtHR, Costa Rica’s ban on invitro fertilization Domestic advocates and their allies in regional institutions have not allowed the norm (mis)translation on violence against women go un-noticed – or without opposition. Acting again through a multiscalar constellation, they have continued their conjoint action to press for the fulfillment of Belém do Pará. In 2004, the Inter-American Commission on Women established a “Mechanism to Follow-up on Implementation of the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women, ‘Convention of Belém do Pará ´’” and incorporated experts from different countries to carry out studies of governmental (in)action. The IACHR undertook research on the systematic neglect of crimes against women in justice systems across the region. In Access to Justice for Women Victims of Violence in the Americas (2007) the IACHR explored why “the vast majority of [crimes against women] are never punished and neither the victimized women nor their rights are protected.” Responding to cases brought by advocates, the Commission has also brokered four friendly settlements (with Peru, Mexico, Colombia, and Chile) under Belém do Pará. Finally, the Inter-American Court 29 has now ruled on seven cases where women and their advocates have used Belém do Pará to protest against their maltreatment (Friedman 2009, 369; IACHR Rapporteurship on the Rights of Women 2012). “In the region as a whole, the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights have increasingly provided an important last resort for advocates seeking policy change and redress for individual violations of sexual and reproductive health rights in their own countries” (Richardson and Birn, 2011, 185). Implementing Anti-VAW legislation IACHR’s Rapporteurship on the Rights of Women: Access to Justice for Women Victims of Violence in the Americas explores why “the vast majority of [crimes against women] are never punished and neither the victimized women nor their rights are protected” IACHR Friendly Settlements: Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Chile IACourtHR Cases: Peru x3, Mexico x3, Guatemala CIM’s Mechanism to Follow-up on Implementation of the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence Against Women, ‘Convention of Belém do Pará’ (MESECVI) When it comes to CCTs, implementation reveals that this class-based policy, clearly focused on poor women, is not, in fact, challenging their position in the gendered division of labor because its design assumes their fulfillment of it. Because CCT programs depend on women upholding their gender roles as mothers and household managers, they can “deep[en] existing gender divisions.” (Molyneux and Thompson 2011, 13). Women are, indeed, targeted in the anti-poverty programs as the conduit for family assistance. But as feminist scholars have found, it is their children who are the main beneficiaries, while women are expected to continue their traditional roles as mothers, often with even more responsibilities. The conditionalities of such programs – ensuring educational and 30 nutritional goals for children – are not “cost-free” for women, who now may be required to engage with another set of social service institutions as well as balance their other economic and social responsibilities. Poor indigenous and Afro-Latin women have an even more difficult situation (Molyneux and Thompson 2011). Gendered assumptions about women’s proper place and “function” are evident in program implementation as well as evaluation. Claims of female empowerment, and the impact of poverty alleviation programs on gender relations, are not the focus of evaluation (Molyneux and Thompson 2011, 11). Instead, “gender equity and empowerment objectives are often treated as secondary, and if they are included at all they are weakly represented and have little or no rights- based or equality content.” (Molyneux and Thompson 2011, 13). Women are effectively being used as “tools of their children’s development” rather than full citizens in their own right. Constanza Tabbush’s comparison of such programs in Chile and Argentina finds that even when programs have distinct goals and strategies, they end up re-inscribing the traditional division of labor as they making women responsible for “lifting their families” out of poverty (Tabbush 2010). Kate Bedford’s (2010) work on poverty programs in Argentina during the economic crisis of the early 2000s reveals that the influence of Catholic norms, transmitted through Church-run programs, ensured that Catholic-inspired “family values,” based on traditional roles for men and women, underpinned efforts at poverty alleviation. Conclusion The decidedly mixed picture of women’s rights achievement in Latin America offers a caution to observers expecting global movement towards women’s empowerment as full citizens: increased political representation is an important step, but can re-inscribe other 31 hierarchies and clearly exists simultaneously with areas of considerable struggle. It is undeniable that the most significant challenges the gender and class status quo – abortion and empowering poor women – reveal the most entrenched opposition. But this picture also suggests that while gender inequality is deeply embedded in regional contexts, it is not an entirely “intractable” problem. Although gendered institutions, particularly informal ones, often intervene in the diffusion of an international norm in ways that re-inscribe gendered relations of power, multiscalar co-operative collectivities have sought allies, particularly at the regional level, to continue to demand the implementation of international and regional women’s rights norms. By considering how advocates interact with formal and informal gendered institutions over the course of international norm transmission, we can better understand the on-going process of women’s rights achievement in distinct arenas. Bibliography Beyeler, Michelle and Claire Annesley. 2011. “Gendering the Institutional Reform of the Welfare State: Germany, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland.” In Gender, Politics and Institutions: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism, edited by Mona Lena Krook and Fiona Mackay, 79-94. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Conway, Janet. 2008. “Geographies of Transnational Feminisms: The Politics of Place and Scale in the World March of Women.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society 15:2:207-231. Bush, Sarah Sunn. 2011. “International Politics and the Spread of Quotas for Women in Legislatures.” International Organization 65: 103-37. 32 Ewig, Christina. 2006. “Hijacking Global Feminism: Feminists, the Catholic Church, and the Family Planning Debacle in Peru.” Feminist Studies 32:3:623-659. Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52:Autumn: 887-917. Franceschet, Susan. 2011. “Gendered Institutions and Women’s Substantive Representation: Female Legislators in Argentina and Chile.” In Gender, Politics and Institutions: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism, edited by Mona Lena Krook and Finoa Mackay, 5878. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. Friedman, Elisabeth Jay. 2009. “Re(gion)alizing Women’s Human Rights in Latin America.” Politics & Gender 5:30: 349-375. ---. 2003. “ Gendering the Agenda: the Impact of the Transnational Women’s Rights Movement at the UN Conferences of the 1990s.” Women’s Studies International Forum 26:4:313331. ---. 2000. Unfinished Transitions: Women and the Gendered Development of Democracy in Venezuela, 1936-1996. College Park, PA: Penn State Press. Helmke, Gretchen and Steven Levitsky, eds. 2006. Informal Institutions and Democracy: Lessons from Latin America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Holli, Anne Maria. 2008. “Feminist Triangles: A Conceptual Analysis.” Representation 44:2: 169-185. Htun, Mala. 2003. Sex and the State: Abortion, Divorce, and the Family Under Latin American Dictatorships and Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 33 Htun, Mala and Laurel S. Weldon. 2010. “When Do Governments Promote Women’s Rights? A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Sex Equality Policy.” Perspectives on Politics 8:1:207-216. Jenson, Jane. 1987. “Changing Discourse, Changing Agendas: Political Rights and Reproductive Policies in Franc.” In Mary F. Katzenstein and C. M. Mueller, eds. The Women’s Movements of the United States and Eastern Europe, 64-88. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Johannsen, Julia, Luis Tejerina, and Amanda Glassman. 2008. “Conditional Cash Transfers in Latin America: Problems and Opportunities.” Inter-American Development Bank Paper. Krook, Mona Lena. 2009. Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide. New York: Oxford University Press. Liu, Dongxiao. 2006. “When Do National Movements Adopt or Reject International Agendas? A Comparative Analysis of the Chinese and Indian Women’s Movements.” American Sociological Review 71: 921-942. Mackay, Fiona, Meryl Kenny and Louise Chappell. 2010. “New Institutionalism Through a Gender Lens: Towards a Feminist Institutionalism?” International Political Science Review 31:5: 573-588. McIntosh, C. Allison and Finkle, Jason L. 1995. “The Cairo conference on population and development: A new paradigm?” Population and Development Review 21: 2: 223–260. IACHR Rapporteurship on the Rights of Women. 2012. “Decisions and Jurisprudence.” http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/women/ (accessed March 29, 2012). 34 International IDEA nd. Quota Project (Database). http://www.quotaproject.org/ (accessed March 29, 2012. Molyneux, Maxine and Marilyn Thompson. 2011. “CCT Programmes and Women’s Empowerment in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.” CARE Policy Paper. Peschard, Jacqueline. 2003. “The Quota System in Latin America: General Overview.” International IDEA Case Study. http://174.129.218.71/publications/wip/upload/peschardLatin%20America-feb03.pdf (accessed March 29, 2012). Phillips, Lynne, and Sally Cole. 2009. “Feminist Flows, Feminist Fault Lines: Women’s Machineries and Women’s Movement in Latin America.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35:1: 185-211. Ramirez, Francisco O., Yasemin Soysal, Suzanne Shanahan. 1997. “The Changing Logic of Political Citizenship: Cross-National Acquisition of Women’s Suffrage Rights, 18901990.” American Sociological Review 63:5: 735-745. Reutersward, Camilla, Par Zetterberg, Suruchi Thapar-Bjorkert and Maxine Molyneux. 2011. “Abortion Law Reforms in Colombia and Nicaragua: Issue Networks and Opportunity Costs.” Development and Change 42:3:805-831. Richardson, Emma and Anne-Emanuelle Birn. 2011. “Sexual and reproductive health and Rights in Latin America; an analysis of trends, commitments and achievements.” Reproductive Health Matters 19:38:183-196. 35 Tabbush, Constanza. 2010. “Latin American Women’s Protection after Adjustment: A Feminist Critique of Conditional Cash Transfers in Chile and Argentina” Oxford Development Studies 38:4: 427-459. Vargas, Virginia and Saskia Wieringa. 1998. “The triangle of empowerment: Processes and actors in the making of public policy for women.” In Women’s Movements and Public Policy in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, edited by Geertje Lycklama a` Nijeholt, Virginia Vargas and Saskia Wieringa, 3-23. New York and London: Garland. Viterna, Jocelyn and Kathleen M. Fallon. 2008. “Democratization, Women’s Movements, and Gender-Equitable States: A Framework for Comparison.” American Sociological Review 73: 668-689. Weldon, Laurel S. 2002. “Beyond bodies: Institutional sources of representation for women in democratic policymaking.” Journal of Politics 64:4:1153–1174. Woodward, Alison. 2003. “Building velvet triangles: gender and informal governance.” In Informal Governance in the European Union,edited by Thomas Christiansen and Simona Piattoni, 73-93. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Wotipka, Christine Min, and Francisco O. Ramirez. 2008. “World society and human rights: an event history analysis of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.” In The Global Diffusion of Markets and Democracy, edited by Beth A. Simmons, Frank Dobbin, and Geoffrey Garrett, 303-343. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 36