Cooper County Jail. - The Missouri Folklore Society

advertisement

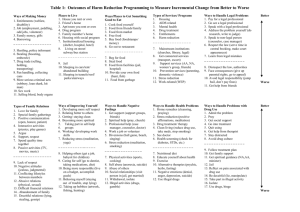

1 Hannah Litwiller Folklore 11/15/2015 “Tales From the Jail” (photographs at end of essay) Folklore and folktales change constantly. As time, culture, and lifeworlds change, oral traditions and stories fade away. However, in one rural Missouri town, an abandoned jail’s stories and legends are still circulated throughout the town, state and even the nation. Boonville, Missouri, located just west of Columbia on I-70, was established in 1817. With a population of about 8,500, Boonville’s small town charm and quirky history makes for an interesting story - and interesting folktales. It was once home to a boy’s military school known across the nation, a reform school and the oldest theater “west of the Alleghenie Mountains” (Friends of Historic Boonville). A central city in an already divided state, Boonville had both Union and Confederate sympathizers and was the center of two Civil War battles. The old Victorian and Tudor inspired houses on Water Street were both Underground Railroad homes and had still-standing slave quarters in the back. Later, in the 20th century, Boonville was a frequented stop for drivers who used Highway 40, which ran through the middle of town. (Boonville Tourism). Boonville has changed as the years have passed. Kemper Academy Military School for Boys closed down in 2002 (Missouri Business), and the reformatory is now a federal prison. Riverboats no longer tour the Missouri river to drop off wares and goods, and the once bustling riverfront now has the Isle of Capri Casino in its place. Boonville is not a main stop for drivers 2 on Highway 40– now, I-70 allows tourists to pass by Boonville without a second glance. Some buildings have been torn down; others has been repurposed or left vacant. There still are remnants of the small town’s history. Thespian Hall, the old theatre, still holds plays, folk festivals and band concerts every year. Murals downtown signify the Civil War battles and honor Boonville’s founders. Many buildings are maintained well thanks to the efforts of local historical societies and private donors. The summer “Heritage Days” festival, programs for school children, and a strong sense of pride and community allows residents to keep passing down the folklore and stories of the small town. The folklore of Boonville and its residents somehow still manages to cling to life – and one building, the old Cooper County jail, thrives on it. Through in-person interviews and emailed surveys, I was able to collect data, stories and other records detailing the Cooper County Jail and its morbid folklore and folktales. History of the Jail The Cooper County jail, located at 614 E. Morgan Street in downtown Boonville, has a rich and interesting history. The jail was built in 1842 and remained open until 1978, when it was closed down for “cruel and unusual punishment” by a federal court. The jail held criminals of both large and small caliber, from famed bank robber Frank James to town drunks to, as time went on, speeders who wouldn’t pay their ticket. (Friends of Historic Boonville). On the outside, the jail is split cleanly into two parts – the brick Sheriff’s office and living quarters, and the limestone that housed the prison cells. Common for small local jails, the Sheriff’s family lived upstairs and interacted with prisoners daily. The sheriff’s wife cooked for the prisoners, often sending the children to deliver the meals to them. While this may be 3 unthinkable now, it was a cultural norm for the times and was practiced until the jail closed down in 1978. (Friends of Historic Boonville) Inside the prison, two floors held the jail cells. The first room, now repurposed for storage, was commonly used for women and children to keep them away from the general population during the 1800’s and early 1900’s. Space for a toilet and a bed are clearly visible in the cell; a window and one lightbulb on a string were the only light sources. Like nearly all of the room, graffiti lines the wall and the door. Some of the graffiti has the prisoners’ names; most are curse words or unpleasant phrases like “It is HELL in here” (Friends of Historic Boonville -Tour Guide Notes). The next cell on the first floor was once a giant “bullpen”, which was reminiscent of a large dungeon and held slaves about to be sent to the auction block. At one time, rings about 1.25 inches were bolted into the outer walls, where prisoners were shackled at the feet. (Friends of Historic Boonville). Eventually turned into several individual cells, there was one window facing the “Hanging Tree” so inmates could see executions without having to leave their cells. On the other side was once a window facing Morgan Street. Some notable graffiti in the “bullpen” includes a small yellow peace sign in the old shower and an “1878” scrawled in the top bunk of the second cell. (Friends of Historic Boonville - Tour Guide Notes). Upstairs, the second-story “bullpen” was completely renovated in 1871 with the appearance of iron box cells. Occupants of the jail were used as laborers to install the cells. According to the Friends of Historic Boonville website, the jail was “to receive no additional major changes for another century”, and it is apparent from the chipped and peeling green paint that is left on the walls. 4 The first cell visible when visitors go upstairs is the “solitary confinement” cell, often used for unruly prisoners or prisoners about to go on death row. Lawrence Mabry, the last man hung in Missouri, spent two years in this cell (Strawhun). There is no bed and no source of light in solitary confinement. Further back behind solitary confinement lie four cramped cells. They are tiny and dark – a 5’5 woman could barely stand up in the cells, much less two full grown men sharing a room. Murderers, thieves, and even speeders – as apparent by the graffiti like “caught speeding, 1977”have spent a night in the small cells. It is hard to imagine anyone living in these cells and staying sane, and, in fact, these cells are one of the many reasons the jail was shut down due to “cruel and unusual punishment” (Friends of Historic Boonville - Tour Guide Notes). Finally, a big jail cell is found to the left of the solitary confinement cell. With three bunk beds, it is larger and easier to stand up in, but is located right by the public toilet used by all the prisoners. Notable graffiti in this cell include multiple swastikas and other dates and names of inmates (Friends of Historic Boonville - Tour Guide Notes). Downstairs and through the backdoor of the jail lies a garden, a gravestone and the remnants of a large tree trunk. Like many other small jails, the tree was the site of many public hangings – a folk practice in itself. “The Hanging Tree” executed criminals in front of eager crowds who wanted to see an example made and the condemned repent. According to a document from the Appalachian State University, “repentance was important because criminals were viewed as no different than ‘normal’ citizens; anyone could conceivable end up facing a death sentence.” In fact, there were so many citizens who watched hangings that Boonville officials often sold tickets for the hanging in order to make a little money for the city. This was 5 normal for the 19th century, but as time went on, the taste for public hangings grew stale in many people’s mouths. Though most northern states had abolished their public hangings in the early 1800’s, believing, “Those who rallied around the scaffold were of a more coarse and vulgar nature; ironically, many were outsiders to the community who would travel to executions for the entertainment value. Their behavior often closely resembled the unruly English mobs ...” (Appalachian State University) public hangings continued until 1930, when the last hanging of the jail – and, according to some, the last official hanging in Missouri – was completed. This hanging was not a public spectacle – and, in fact, was very private, with only a few doctors, lawyers and other officials to witness it. It took place in what is now known as “The Hanging Barn”, originally built in 1878 to house the sheriff’s horses and converted into a gallows specifically for the hanging (Friends of Historic Boonville). The barn is kept up, and the gallows along with it. Tourists can visit inside the barn and climb the “unlucky thirteen” steps – another common folk superstition – to peer over the edge and imagine the death. After the jail was closed, a local historical society –the Friends of Historic Boonville – took over the building and turned it into their headquarters. It is now both an office for the Friends and a tourist site, where visitors from all over the country pay a visit to what is now just a ghost of its former self. Jail Folklore An interesting genre of Boonville history lies behind these old walls. As time goes by, the stories Boonville tour guides and residents tell about the old jail get passed down and changed. “We share lots of stories…some are even true,” recalls Melissa Strawhun, Executive Director of 6 the Friends of the Historic Boonville and Boonville resident for 13 years. The Cooper County Jail was open for over 130 years and was the site of death, misery and “cruel and unusual punishment.” Many local residents can still remember the jail when it was in use, and some even remember their peers arrested and staying overnight in the jail, including Steve Litwiller, a resident of Boonville for 58 years. He said, “One classmate of mine was actually the real reason why they closed the Cooper County Jail. His name was Antonio Quint – his nickname was “Mutt” – and Mutt’s lawyer came in and just couldn’t bear the conditions – so he went to court and had the place closed.” One common story told by members of the Friends and Boonville residents is the legend of Frank James, outlaw and Jesse James’ older brother, who spent a night at the Boonville jail. According to the Friends of Historic Boonville’s website, the official story is this: James was brought to the Cooper County Jail by Sheriff John Rogers on April 24, 1884 to answer a warrant for his arrest for a train robbery. Sympathetic citizens of Boonville raised his bond in a matter of hours, and the case was later dismissed for lack of evidence. However, according to Kathleen Conway, historical archivist and Boonville resident since 1992, there is more to the story than Frank James’ popularity in Boonville. She says, The story about Frank James piqued my interest when we received the original bond signed by local residents that allowed James out of jail. In checking the date of the bond—it is after Frank James was pardoned by the Governor of the State of Missouri. But for some reason Cooper County decided to pursue him for robbery. Technically Frank James was no longer an outlaw when the county arrested him—so he wasn’t quite as notorious as we usually say in the tours. In the county records in the archives you see him called to trial and then a couple of continuances were granted. Eventually the case 7 was dropped. Guess Cooper County was just too stubborn to let the case drop, even after the State had pardoned him! (Conway) Another story told often is the story of “the last man hung in Missouri”. The official website of the Friends of Historic Boonville states, “On January 31st, 1930, Lawrence Mabry, 19, climbed the 13 steps to the loft and was “hung by the neck until dead” for a robbery and killing in Pettis County. This hanging was a contributing factor in the elimination of the county capital punishment.” (Friends). However, the nice and neat version told of the “last man to hang” is not as clean-cut as it seems. In Death Sentences in Missouri, 1803-2005, author Harriet Frazier writes about the crime and the execution of Mabry, who was mentally handicapped. He could not read or write and could barely form the letters of his name. She says, “He hoped to read the Bible while in jail awaiting his hanging; doing so was far too difficult a task for him. He said immediately before his death, ‘God is at my right elbow,’ and he surely intended to say, “God is at my right hand” (130). The family of Lawrence Mabry had campaigned to get their son’s sentence commuted, but were unable to convince a judge or jury otherwise. In addition, Melissa Strawhun recounts a tour she gave to the great nephew of Lawrence Mabry. I didn’t know he was the great nephew until I took him upstairs and was talking about the death row cell and of course was telling the story about Lawrence spending two years in the cell. He stopped me and said “I guess I should tell you that Lawrence Mabry was my great uncle and that we [the family] still believes he was innocent and was wrongly convicted and ultimately killed, especially since he was only 19. (Strawhun) Folklore about the “sad business” of Mabry’s death is still recounted and told today in many different genres. For example, the late folk singer Bob Dyer’s song, “The Last Man to Hang in Missouri” was recorded in 1983 and is still occasionally performed today. The song, 8 while accurate in a lot of ways, is technically false in many others. Dyer paints a picture of a real outlaw, not a mentally handicapped boy: “Shot a man for two half dollars and some nickels just for fun” (Dyer). Mabry’s story is a cautionary tale, advising listeners to listen to their mothers and not get on the wrong side of the law. The chorus of the song, too, is partly inaccurate: “The last thing he said was ‘I wanna die smiling’/the last thing he heard was the hound dog’s mournful wail.” According to Frazier, of course, his last words were the misinterpreted, “God is at my right elbow.” However, both Frazier and the Friends of Historic Boonville claim the ‘hound dog’s mournful wail’ bit is true: “Mabry’s body hurtled through a sawed-out hold in the loft floor at 9:17 a.m. Simultaneously, the sheriff’s dog, Chief, in his pen near the barn-garage place of execution, began howling and continued howling for the next five minutes.” The Lawrence Mabry story is not the only death recounted at the Cooper County jail. Other death and execution stories at the jail are told, sometimes by tourists themselves. Melissa Strawhun often hears new bits and pieces of stories during tours: During Heritage Days last year we were giving a tour to the Davis family because they were in town for a family reunion. Casually, during the tour of the cells downstairs, one of them asked the group of they knew which cell “cousin Scotty hung himself in.” They said he hung himself in one of the cells in 1977 because he was going to prison for a long time and he obviously didn’t want to go...he was 22 years old!! Other official deaths at the jail can be found in Death Sentences in Missouri, 1803-2005, including the story of Charles “Spinner” Reeves. His hanging is pictured on a bulletin board inside the offices of the Friends of Historic Boonville, and is often mentioned by tour guides when taking visitors around. Conway says, “We have the marriage license of Spinner Reeves— the man whose hanging was photographed. He was a local guy living a regular life—then 9 something happened that resulted in his hanging.” Frazier goes deeper into the story in Death Sentences, giving a time, reason, and place for his hanging: “On February 24, 1902, Charles Reeves shot and killed his wife, from whom he was separated, when they met him at a dance and she called him a liar. He was tried and convicted of first degree murder within a week of his crime, and his legal counsel did not appeal his client’s conviction. The sheriff hanged him on May 23, 1902” (233). Another form of folklore for the Boonville jail are ghost stories. Interns and workers of the jail have seen shadows and heard noises. According to Strawhun, one commonly told tale is the story of the ‘glue stick’: “We were looking for glue because the intern was making a poster and we couldn’t find any so I was supposed to go buy some that night. Well, of course I forgot to get the glue but when we came to work the next day there was a single glue stick sitting on the desk and we didn’t know where it came from” (Strawhun). While Strawhun had never seen a ghost herself, other former directors of the jail have had creepy experiences. Some of these ghost stories from the jail have been published in a book by Boonville resident Mary Barile, entitled The Haunted Boonslick. After conducting interviews with a former director of the Friends, Barile quotes one creepy encounter from a former director: Suddenly the lights went out and I was in pitch black darkness. I thought my sister, who was there helping in the office, was playing a joke on me, but I was pretty shaken up and felt my way to the door and then down the hall. I yelled at my sister – who, it appeared, hadn’t left the office. Those lights had gone on and off a few times, but only when I’m working in one of the cells. We’ve had the wiring checked and the systems repaired – everything is fine. But I’m not going into that cell alone ever again. (Barile, interview) 10 Occasionally, the Friends of Historic Boonville bring in paranormal investigators to check out the ghosts and spooks that may reside in the jail. On October 24, 2015, the Friends hosted their most recent ghost hunters – who apparently found a lot: The one really interesting thing that came out of the paranormal investigation we did last weekend occurred in the 3rd cell in the farthest hallway (where the 4 small cells are located) there was a lot of “paranormal activity” such as flashlights been turned on and off when we asked if anyone was in there. Now, normally I would be questioning all of that… but last Monday, before the paranormal investigation, the Sherriff’s department brought in their new dog, Grimm, to take pictures of him inside the jail. That dog was totally freaked out by that same cell and wouldn’t go in…he sat by the door in the hallway and was waving his paw in front of his face like he was swatting something away. I didn’t tell the paranormal group that because I wanted to see if they could find anything on their own and sure enough that was the cell where all the “activity” was so I don’t know what happened in that cell but something is going on. There was also a lot of “orbs” flying around, you could seem them on the monitors they had set up. (Strawhun). Analyzing The overarching themes of these folk tales from the Cooper County Jail all, of course, involve death and misery – as wrongdoing, jail and executions tend to have. Interestingly enough, many of the stories and superstitions in the jail have easily identifiable motifs and genres that can be picked out from other samples of folklore. For example, the tale of Lawrence Mabry, especially the Bob Dyer version, is painted as a wrongdoer or a scoundrel who didn’t listen to his mother: “Mama tried to slow him down/took 11 him down to Sedalia town/by then there wasn’t much she could do/he was the last man to hang in Missouri.” Though this is inaccurate, it is quite close to Meryl Haggard’s “Mama Tried”, written in 1968. “And I turned twenty-one in prison doing life without parole/No-one could steer me right but Mama tried, Mama tried” (Haggard). The similarities between the two songs are obvious: a rebellious young man cut down in his prime because he didn’t listen to older people and wise advice. It is a cautionary tale for criminals, and the motif – to scare listeners – echoes in the lyrics. Other themes prevalent in the Lawrence Mabry story include the idea of an innocent person executed– or, at least, a person who did not deserve to die. The Lawrence Mabry tale is able to show the injustice of his execution by expertly introducing supernatural elements to the folktale like the dog barking at the exact moment of Mabry’s death. This supernatural element – combined with the line “God is at my right elbow” – shows the uneasiness of the public about his death. Lawrence Mabry’s trial went to the Missouri Supreme Court; he was waiting in jail for two years in a highly publicized case while he maintained his innocence (Melton). Adding supernatural elements in – along with an anecdote about his innocence and supposed stupidity – suggests a greater power aware of the injustice that occurred in 1930. Another example of an analyzation in folklore is the Frank James release story. Though Conway claims the story is much more than the original Friends of Historic Boonville summary on their website, it seems like the legend of the “Folk Hero” is clearly shown in just a few sentences. The townspeople viewed James – a murderer and a thief – as a hero, and let him go. Like his brother, Jesse James, Frank James was considered a “clever hero.” According to Orin Klapp’s “The Folk Hero”, found in the Journal for American Folklore a “clever hero” “either escapes or vanishes from a formidable opponent by a ruse. The victory of the clever hero is 12 brains over brawn.” While James didn’t trick anyone explicitly, he was at least able to supposedly convince the townspeople he was a good person. In their eyes, he was a folk hero – although, in this day and age, he may have just been considered a common criminal. Another folk practice hidden inside the jail include one written on its very walls. The graffiti found throughout the place – “Troy Fenton”, “Arrested for Speeding” “It is Hell in here” – is considered folklore itself. These markings on the walls have many different functions, which is common in graffiti. According to Thomas Green, of Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art, Volume 1: “Graffiti ranges in form from doggerel to epigrams to slogans to single words, often personal names and name-places” (424). These etchings on the jail all have different forms and functions. There’s the vulgar – curses of “Fuck You!” are throughout the jail – the simple names and dates: “X was here” – and even turf war elements with the swastikas on the second floor of the jail. The graffiti at the Cooper County Jail may not have been originally intended for tourists, but as time goes on, has become a morbid testament to old school crime and punishment - or, at least, one where speeders get locked up for the night in tiny cells. Conclusion While the Friends of Historic Boonville don’t mind sharing their stories to others, they don’t mind a profit on the jail - visitors pay five bucks a pop to tour the two-story building. However, the stories and ways they give tours change overtime. As Kathleen Conway says, “I think the tours and stories have become more fact-based. We are adding more info as we find out more.” When artifacts and clues arrive at the Friends of Historic Boonville, more information is added into the tour. The oral history of the jail is passed down from generation to generation of 13 intern and workers, but the stories get updated frequently, and the little bits of information given on informal tours can get a little disjointed over time. For example, Christine Salyer, a Boonville resident for 18 years, remembers different stories she was told by tour guides of the jail in various points of her life: “I remember the first time I toured the jail, I thought the Hanging Barn was where they hanged everybody – all the people executed. But when you [the interviewer] gave me the tour, you said that only the one guy was hanged there. So the stories changed.” (Salyer) As more ghost stories are added to the repertoire of lore and legend told at the jail – Strawhun plans to add the paranormal investigator’s finds to the script of the tour guides – the jail’s allure grows stronger. According to Strawhun, the “Ghost Hunters” of the SyFy show have called and asked to visit the jail, and folklorists such as Mary Barile have included the jail in their books and studies. The Boonville Jail has been standing since 1842, and must have countless other stories than the ones told above, which I was unable to find due to limited resources and time restraints. A visit to other local residents and even a dig through the Boonville archive files could turn up even more interesting and gruesome details from the jail once closed for “cruel and unusual punishment.” And a person with an overactive imagination may not be able to stop themselves from trying to understand what the jail was really like. The Friends of Historic Boonville website concludes their webpage on the jail with a simple paragraph to engage their readers: But with a little imagination, you can hear the footsteps of the sheriff as he walks across the floor to one of the cell doors. The huge jailer’s keys clang against each other. There is a pause and then the sound of a brass key entering one of the old iron locks. For some, it 14 turns to the right, opening the door and letting them out, giving them a second chance. For others, the key turns to the left, closing the door behind them, sealing their fate. (Friends) The folklore of the Cooper County Jail is circulated through every tour, school education session and book read about Boonville. It may not be known to residents outside of the area, but inside the “Boone’s Lick”, the jail’s creepy backstory and gruesome tales is a staple of the county. This small Missouri town takes pride in the former “cruel and unusual” jail, but remembers to take heed of the legends and warnings associated with the place. As Salyer says, “It’s pretty cool, but it’s creepy. I definitely don’t want to be there alone at night!” Editor’s note: Musician Dave Para of Boonville wrote – “Well, we have certainly known Hannah a long time and her lovely and talented parents, Steve and Debbie… (he includes a link to a version of the song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXkNntoGW8g ) We had a fine rock version on the Wandering Fool album. Bob later found out Mabry was not the last man to hang…” (the last public execution in Missouri, possibly in the US, may have been at Galena MO, when “Red” Jackson was executed May 21, 1937, for murdering a traveling salesman for his car and $18; some claim that the fence the sheriff erected to limit viewing to the 400 or so ticketholders disqualifies the event, and hand the distinction to Owensboro KY (Rainey Bethea, August 14, 1936) , where no fence had interfered with the macabre spectacle. 15 https://hootentown.wordpress.com/2011/03/02/%E2%80%9Clast-hanging-in-the-state-ofmissouri-%E2%80%9D/ Dave continues: “Bill McNeil did a review of Bob's album years ago for the Ozarks Mountaineer, and in a rare mistake identified the man as “Jim Higbie,” who was a longtime friend of Bob's and did some of the historic survey work with him. Bill's mistake caught a couple of laughs around town.” Bibliography Appalachian State University. “Public Executions.” N.d. Retrieved at http://gjs.appstate.edu/media-coverage-crime-and-criminal-justice/public-executions on November 1, 2015. Barile, Mary. The Haunted Boonslick. The History Press. Print. 2011. Conway, Kathleen. Interview. October 29, 2015. Dyer, Bob. Song. “The Last Man to Hang in Missouri.” Big Canoe Records. 1983. Frazier, Harriet C. Death Sentences in Missouri, 1803-2005. McFarland and Company. Print. 2006. Green, Thomas. Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art, Volume 1. Print. ABC-CLIO. 2010. Friends of Historic Boonville. “The Cooper County Jail and Hanging Barn.” Retrieved at: http://freindsofhistoricboonvillemo.org/?page_id=128 on November 1, 2015. Friends of Historic Boonville. “Thespian Hall.” Retrieved at http://freindsofhistoricboonvillemo.org/?page_id=111 on November 1, 2015 16 Friends of Historic Boonville. “Tour Guide Notes.” Retrieved in person at old Cooper County Jail. October 10, 2015. Haggard, Meryl. Song. “Mama Tried.” Capitol Recording Studios. 1968. Klapp, Orrin. “The Folk Hero.” The Journal of American Folklore. March 1949, pg. 17-25. Litwiller, Steve. Interview. November 1, 2015. Missouri Business Development Program. “Kemper Military School Redevelopment Program”. Retrieved at http://missouribusiness.net/2013/03/kemper-military-school-boonville/ Melton, E. J. History of Cooper County. Self-Published. Print. 1937. Salyer, Christine. Interview. October 28, 2015 Strawhun, Melissa. Interview. October 30, 2015 Gallery: Old Jail and Hanging Barn: 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29