Why History Matters

advertisement

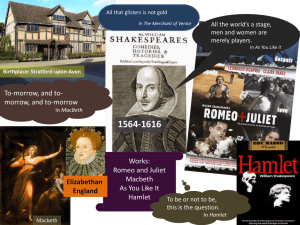

David Magill October 28, 2013 Why History Matters to Me I ran into a colleague recently, and when the subject of tonight came up, the person asked, “Why are YOU speaking on history?” Indeed, it must seem odd to have me up here, in between these wonderful historians, when I do not study history. I often get this question as well in my day job as a literature of diversity professor: “what are you doing here?” Or “You’re a white guy – what do you know about diversity?” Or “You’re a dude – why are you teaching women’s studies?” So I’m used to being looked at critically. Just by giving this talk tonight, I am already heading into dangerous ground. That’s okay, though – danger is my middle name. I know we’re all coming down from our fall break sadness, and I can hear the sirens calling me to sit down, but you see, I feel the need to testify. I am a champion, and you’re gonna hear me roar, ladies and gentlemen, because history is actually quite important to me, and it should be to you even if you are not a history major – and not just because we can ‘learn from our mistakes’ because, if Congress is any indication, we never do. No, my friends, history is important because history is who we are – it defines our identities in important ways, both individually and collectively. History is the story of us, and the definition of “I.” William Faulkner famously said, “The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.” Our pasts define and influence us every day in conscious and unconscious ways. So, history is always about the present as much as it is about the past. We write ourselves into being personally and collectively through our histories. As Gordon Sumner – or as you know him, Sting – famously wrote, "In this theatre that I call my soul, I always play the starring role." We all understand ourselves as coherent individuals – how many times have you said, “I am …” today? We know ourselves as a “self” – but how do we know that? Because we tell ourselves a history in which we are the heroes with a set of values and ideals that we consciously believe in and always follow. We construct a past through our memories that makes us who we want to be – even if deep inside, we know we are not that person. Or not fully. No one writes their self vision and thinks, I am a supporting player. We are all strutting and fretting our hour upon the stage, playing to the crowd and trying to be the star. And that's okay -- but often our story leads us to leave out the bad parts, the embarrassing parts. In the narrative of my romantic life, I am often the Casanova. I got jiggy with it. I kissed the girls and they liked it. But that story does not always highlight the failures. I can tell you how I wooed various women to date me, but I rarely talk about Alexis Brenner, who I am pretty sure liked me, but I was too nervous to confirm until it was too late and she had a boyfriend. I pined away for Mary Pollard through most of 7th grade, but she would not give me the time of day. And then there’s Kristen, who was my girlfriend for 72 hours in 7th grade, then dumped me because I was too nervous to actually hold her hand in public. Traci Chapman said it best: "There is fiction in the space between the lines on your page of memories. Write it down but it doesn't mean you're not telling stories.” Of course, I do know these stories – but they do not present my best self. However, I need to incorporate them into my history, even if it is my own private Idaho, or else I am untrue to my own past. Then again, even counting on memory is a flawed strategy – I remember nothing of 2nd grade but trying to kiss Lisa Johnson on the head, and leaving a 3 Musketeers bar at a snack shop and having my mom yell at me about not paying attention while my sister sat there and ate her M & M’s and laughed at me. Clearly, more must have happened, and it’s important stuff like learning how to multiply and what the scientific method is – but I don’t “remember” it. So it’s part of my history and yet not. We do this collectively as well – as a community and as a nation we strive to write ourselves into being by telling the story of our past. But historians remind us that it is a story, and it’s one that we should approach with some principles – ideals that include rather than exclude and that capture the story of all of America. For example, how many of you know you rode through the countryside to warn our soldiers that “The British are coming!” Yes, Paul Revere. But how many of you know who Sybil Ludington is? The “female Paul Revere” – that label itself is reductive – she rode through 40 miles of rainy night with enemies all around to warn the Americans that the British were burning Danbury, Connecticut. Why do we leave her out? Well, she does not fit our “founding fathers” vision of the nation’s birth – and to have a maleonly birth is quite freaky. The early national story has always been a story of white men – and only recently have we expanded it to think more about those many others who contributed to our new world. But our nation’s history is replete with such omissions. On a more personal level, we might look at Daniel Snyder, rich businessman and owner of the Washington football team – and I am a huge fan of this team. But as Sherman Alexie pointed out during his visit here, Snyder writes a history of the team when he says that the team has “an 81-year history of honoring Native Americans with the name” – and that history neglects to note that the team refused to integrate until the NFL threatened to kick them out, and that the team’s fight song originally contained references to scalping and language that suggested Indians were illiterate children. Problematic? I think so. Even in my field, this happens. We historicize literary study and spend a lot of time discussing dead white guys at the expense of what Nathaniel Hawthorne called “that damned mob of scribbling women” – by which he meant those women that were outselling him in the marketplace 3 to 1. Dr. Smith and many of our students would argue that William Shakespeare is the greatest writer in Western culture – he thought of it all 400 years before anyone else. OK, let’s consider Shakespeare for a moment. His plays were certainly important, but he wrote for the “commoners” in the pit as much as for the royal personages and intellectuals that would make him an object of study and put him on our scholarly pedestal. And his reception has certainly changed. For example, English physician Thomas Bowdler was the most famous of individuals who published a revised version of Shakespeare’s works which “cleaned up the text” and focused on the “beautiful parts.” 19th century America studied Shakespeare through the printing and performance of “great speeches.” Thus, if you saw Romeo and Juliet then, you saw “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou, Romeo.” But removed (in order not to offend delicate ears) were the opening scenes, such as the one where Romeo and his friends indulge in a variety of penis jokes and sex talk: “A dog of that house shall move me to stand” (translation: even the ugly ones arouse my genitals); ‘I will push Montague’s men from the wall, and thrust his maids to the wall” (Kanye West translation: “I’d make the homies step back and then tap their bitches.”) Thus, Romeo and Juliet become great lovers, not an idiot hormone-driven teenager with his trash-talking friends and his smarter, though still young girlfriend. Even Shakespeare changes. And for many years the critical consensus was, ‘Shakespeare can’t be the focus of discussions about race – he never would have seen a black man.’ Now we know better, and so we can (and should) discuss his views on race, for he has written them for us to see. Those definitions change over time – those “scribbling women” I referenced have become for contemporary scholars a recovery of texts of importance. And scholars have made persuasive arguments for their study, anthology editors have made persuasive cases for their inclusion, and readers have made compelling claims for their relevance. We revise our history to better capture the whole picture – and that’s the importance of history as a field – to get toward a more truthful and ethical vision of the past and the present. We include these women not, as one e-mail to me suggested, to “undermine our common Judeo-Christian heritage in an effort to promote groupism and group-think which is then exploited to create division.” The “common heritage” argument often arises as a response to canon expansion – yet whose heritage are we discussing? And what counts as my heritage? My Scots-Irish roots, which would have us reading Ivanhoe and Dubliners? My American-ness which, by this account, includes Hawthorne and Melville but not Catharine Sedgwick? Hemingway but not Cogewea? Faulkner but not O’Connor (herself a woman religious writer)? Who counts as American? History, and professional historians, help us by making us aware of our narratives and by challenging us to find new ways to write those narratives and incorporate more voices into the conversation. We use history – the stories of then to define our “self” – that collocation of material, psychological, and emotional baggage that makes you the unique little snowflake you perceive yourself to be even as you participate in the ultimate game of follow the leader. So why is history important? One, because it re-defines the human (in its insights and its blindnesses), but two, because it defines our community’s social imaginary. We construct history together – students and faculty – in what we teach, in what classes you choose to take, in what you remember and forget and write down, text, or take a selfie in front of. You play an important role in determining what we read, just as what you read determines possible versions of you. Considering the social world that constructs who we are, discussing the social constructions that inform what we read, and examining the textual remnants that constitute from whence we came – these projects are crucial to history and the humanities, for they help to understand what we value and why, and teach us who we were, are, and will be, whether it’s to understand Farmville’s race relations, to appreciate the beauty of a Grecian urn, or to comprehend the quiet desperation of the mass of men. To paraphrase Thoreau, a man who would have appreciated an homage to Reverend King, we seek to know what we live for, and how and why. That truth may be beauty, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and though we may think we are beholden to no man, I know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee. You want me to tell you the truth? You can’t handle the truth! And when I stick my hand in a big pile of goo that used to be some guy’s face -- Forget about it, Marge, it’s Chinatown. As you can see, my history involves a lot of TV and books – or at least, that’s my story and I’m sticking to it. But if you want to learn about all these references I have made, you need a history teacher. And I hope you can write your histories, at least the secret histories of your soul, to be more honest and more inclusive.