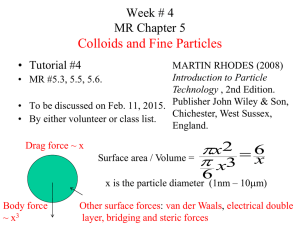

Only a fraction of all analytical technique for particle characterization

advertisement