Municipal Affairs Act

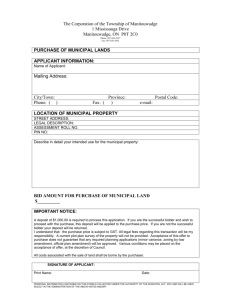

advertisement