Linda_Knight

advertisement

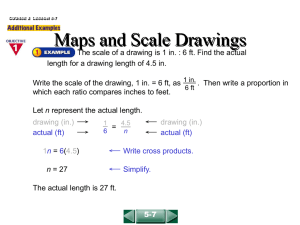

Published in TRACEY | journal Drawing Knowledge May 2012 Drawing and Visualisation Research DELEUZIAN DOLLS: SUBVERTING MOTHER/DAUGHTER IDENTITIES THROUGH INTERGENERATIONAL COLLABORATIVE DRAWING Linda Knighta a Queensland University of Technology, Australia This paper explores concepts of desire and rhizomatic working through a series of intergenerational collaborative drawing episodes. Particularly, mother/daughter relationships are examined via drawings created by the author and her young daughter. Drawings hold on their surface unpredictable connections to things experienced, known, conceptualized and imagined. In the context of this paper desire is seen to drive adults and children into expressing and making a mark, to make an imprint. Here, the prompts that inform a drawing are regarded as a rhizomatic network of chaotic actions and thoughts that connect each drawer to the tools, the paper and each other in unpredictable and mutable ways. The paper concludes by discussing how these intergenerational collaborative drawing episodes offer opportunities to re-imagine relationships, communications and learning in early childhood education. www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/ sota/tracey/ tracey@lboro.ac.uk TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 DRAWING AS COMMUNICATING The drawings discussed in this paper are the result of a number of intergenerational collaborative drawing activities between my daughter and I. It was a collaborative process, as distinct from drawing in tandem, or interactively in the sense that both the mother and child actively referred to the same stimulus (in this case dolls) while we drew on one sheet of paper. We collaborated in terms of being actively willing to undertake a drawing, and we collaborated in terms of beginning with the same stimulus, but we made no predetermined agreement on what our respective contributions might contain, or on how each finished drawing might look. Toy baby dolls and stacking ‘Russian’ dolls were placed near the paper, but there was no pattern or assumption about how they might be referred to in our drawings. Even though our drawings are collaborative, we drew at the same time rather than ‘together’ to make ‘one’ drawing (a common term used in early childhood education in relation to intergenerational arts activities). To this end, each of the drawings we produced contained aspects that merged, aspects that sat apart, aspects that traced and overdrew. These drawings then, look markedly different from many that are commonly produced by adults and young children individually. Intergenerational collaborative drawing interrupts historically dominant early childhood drawing models that regard childhood art-making as personal, and a young child’s drawing as being sacred and private (Lindstrom 1957; Lowenfeld 1975; Richards 2007). Childcentred pedagogies are often favoured in contemporary early childhood teaching manuals (Herberholz & Hanson, 1995; Schirrmacher, 2006; Bouza Koster, 2005) that student teachers access and learn their teaching knowledge from, so these help to maintain a dominant view of children’s drawing and painting as something that an adult shouldn’t interfer with. Intergenerational collaborative drawing undermines that untouchability. Not only does drawing collaboratively encourage adults and children to produce drawings collectively, the experience of working at such close range can provide adult and child drawers with a greater range of ideas and encourage them to push beyond their usual visual choices. Intergenerational collaborative drawing contests education pedagogies that advocate for solitary drawing, which can become laden with conventional visual schema such as houses, rocket ships, people, monsters. Drawing is not related solely to art production and should not be sentimentalised by adults. Although images of children’s drawings often adorn websites, school hallways, greetings cards, for a young child, drawing is sometimes but not always an isolated activity and it isn’t always undertaken for art’s sake but can serve as a major communication tool to process experiences, ideas and concepts about all manner of things. 1 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 It can be difficult however for an adult to access information about these concepts in a drawing that is produced by a child and then seen by the adult only on completion. By preparing for and undertaking a drawing with children, adults can have much more detailed exposure to a child’s imagining and theorising about things. Because they are working with a child at close range they can have higher quality communication with children, and in respect to education, teachers can engage in visual-based activity that is much more rich and informed than providing a pre-drawn template of something to be coloured in. Intergenerational collaborative drawing is mutually beneficial because it facilitates more equitable exchanges of ideas, thinking and responding in a number of adult/child contexts. It is important to challenge conventions around children’s drawings not just to improve communication between adults and children. A persistent and dominant view in Western education sees drawing as a useful preparation for the transition into writing (Caldwell & Moore 1991; Olson 1992; Rich Sheridan 2002). This drawing-to-writing discourse suggests that drawing is slowly disregarded as a central communication tool as a child matures, and that this is a part of their ‘natural’ (i.e. it is automatic, universal) development. I suggest this is not a natural transition but a learned one, influenced by many factors including family, friends, curriculum, media, society. In the main, children do slowly begin to rely upon the written word more than the drawn image to convey their ideas and theorisations, however those who do persist and continue to use drawing as a central language can commonly be labelled with titles of difference: arty-farty, creative, talented (as opposed to academic), wacky. This hierarchical regard for reading/writing competency needs to be dismantled; it no longer reflects a global shift towards multimodal processes for information distribution and reception. The quality of learning and communicating that occurs during a collaborative drawing activity helps to challenge this writing hierarchy by giving positive messages to children and adults about the value in using diverse communication skills, in early childhood and well beyond. CHALLENGING DOMINANCE This paper focuses on a drawing process that involves both adults and children. Irrespective of a familial or pedagogic relationship between the drawers this process inevitably raises issues of dominance and power. It is a challenge to reconceptualise dominant values and theories around parent/child, or teacher/child relationships, particularly because many of them seem to support childrens rights and individuality (Ghandini et al, 2005). I am interested in contesting conventional ideas about mother/daughter relationships that commonly present the mother as ‘expert’ knower and the child as ‘empty’ learner. I see instead that mother/daughter identities can be fluid and unpredictable, that power doesn’t 2 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 always reside with the mother, and that mother and daughter identities are far more complex than simply dividing the mother’s identity between “the work/home, public/private” (Stephens, 2004, p. 90) stereotype. Confronting stereotypical norms that surround mother/daughter relationships provides opportunity to challenge and dismantle constructed truths surrounding these roles, and to re-examine familial assumptions and practices around who holds power and when. Dobris & White-Mills (2006) suggest that patriarchal dominance may be disrupted through “alternative feminist discourses” that challenge “traditional views of women and mothering” (p. 35). Dolls were used for this project as a stimulus and as an antagonising object to think about ‘mummies and babies’. I chose baby dolls as they present plastic, enculturated symbols of motherhood/babyhood. I chose ‘Russian’ or stacking dolls for their visual and cultural contrast to the plastic baby dolls. While the purpose of stacking dolls is similar to that of the baby doll (a child’s toy that facilitates parental/familial role plays and scenarios) their visual distinctiveness and physical characteristics provided us with different compositional choices. By basing our collaborative drawings on these dolls, we had opportunity to dismantle and re-imagine the mother and baby roles that surface when they are played with. Drawing together enabled us to begin to examine and challenge those residual objectivities around mother/daughter identities. Because the aim was not to faithfully reproduce the objects as a series of still life images (which might then separate us as drawers due to our respective skills and experience in that genre) drawing collaboratively and responsively (adding to each other’s marks and symbols rather than each doing a drawing of the thing in front of us for example) helped to flatten out relational hierarchies which might exist between us at other times. Collaborative drawing connected us as mother/daughter through “communicable experience and empathetic understanding” (Brakman & Scholz, 2006, p. 54). The drawing act connected us to each other’s thoughts and ideas and enabled us to work ‘outside’ our subjective and physical selves. Our collaborative drawings explored how or whether my mother and her daughter identities and intersubjectivities could be contested and dismantled through a shared activity. I value my relationship with/to my child. However rather than uphold a one-directional responsibility of me managing her growth and development, through drawing she and I can reform and reciprocate our intersubjective roles through a continuing process of discovery and exchange. Our respective responses were not predetermined, and I believe we were able to neutralise the culturally dominant mother/daughter role expectations we might perform at other times. The drawing gave us opportunity to subvert otherwise present adult/child hierarchies that play out in everyday life.. 3 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 DELEUZIAN DOLLS This paper explores mother/daughter identities through written text, video footage and drawings (figures 1 – 6). FIGURE 1. OIL PASTEL, COLOURED PENCIL ON PAPER 4 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 FIGURE 2. OIL PASTEL, COLOURED PENCIL ON PAPER 5 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 FIGURE 3. CHARCOAL, COLOURED PENCIL ON PAPER FIGURE 4. PASTEL, CHARCOAL, OIL PASTEL ON PAPER 6 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 FIGURE 5. CHARCOAL ON PAPER FIGURE 6. CHARCOAL ON PAPER 7 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 The cultural texts (peer modelling, advertising, stories, film) that guide young girls in their play and relationship building with baby dolls present distinctly gendered norms and expectations around maternal, and nurturing skills. Because adults (who are not necessarily women or mothers) are responsible for the design and marketing of such dolls these toys essentially represent an adult’s rather than a child’s construct of what a baby ‘is’. However, not only is a baby doll a mute, emotionless version of a human baby, its visual and physical manifestation firmly situates it within a cultural ideal of beauty, ability, physicality, gender. Baby dolls were chosen then because they contain many layers of meaning - the doll as baby, producing drawings of dolls that look like babies, drawings created by a mother and daughter who share I am/have baby experiences. Stacking dolls were chosen because they present a conceptual and visual contrast between the replica, plastic baby doll and the stylised, handcrafted inter-stacking dolls, and they reference different cultural examples of familial play items. Our drawings were created at different times over an 18-month period, between 2008 – 2009. My daughter was then aged between 3 and 4 years old. Before we drew I asked my daughter if she was happy to participate, and also if she was happy for the event to be filmed. I was careful to explain to her that the purpose for drawing was to draw the dolls and think about ’mummies and babies’. If she was ever not interested in drawing or being filmed we did not continue with the activity. Film footage of these drawing events facilitated observation of us as we drew, and the multiple ways that we communicated as we drew. I now present a commentary that responds to the drawing occurrences contained in the video data. We were often deeply immersed in drawing. This intensity flowed into how we responded to materials, the environment, the dolls, easel and drawing tools. We engaged in cycles of silent and non-silent co-drawing, the silence or speech initiated randomly and independently by either of us. I tried to avoid discussion via questioning but preferred in the main to respond to my daughter’s commentaries, to try to lessen the possibility of me shaping her experience or ideas. As we drew she often sat on my lap, and this forced an intense and fluid physical interaction of our bodies as well as forming a barrier between the paper surface and each of us. Personally, whenever this occurred I was forced to change my usual, familiar drawing practice to one that negotiated my daughter’s body space. I found through this that I began to revisit childhood bodily practices that seemed more chaotic to me. My daughter liked to initiate this physical, intertwined way of working – so maybe for her this seemed a more conventional way of drawing. Our interactions were often playful – for example the action of scrubbing charcoal into the paper and then blowing the residue off began to resemble a game where each of us took turns to blow charcoal dust off the paper surface. This game also occurred when marks were made and then erased, and the eraser residue was blown off the paper. However this 8 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 erasing/rubbing out performed a dual role of being playful as well as symbolising the unpredictability of our progress and how chaotically we disrupted more conventional (adult) drawing practices. The action of erasing/rubbing out belied a deeply antagonistic act of toppling a conventional adult/child power relationship; my daughter was able to simply and effectively wipe out all my work without warning. I found this both extraordinary and confronting. Although these drawings are the manifestation of a research investigation, and therefore I made myself open to whatever might occur as we drew together, I do not usually experience erasing out of my work by someone else. These drawing episodes forced me to confront my own reactions to losing control over the content and direction of a work. I was aware that this might be the experience for my daughter also; each of us were creating drawings in unfamiliar circumstances, and negotiating the presence of the other. The drawing acts we undertook during our collaborations enabled me to think critically about the usual power relations that reside in parent/child relationships. As we drew we each constantly disrupted and intercepted what the other was doing, forcing each of us to embrace the unpredictable and work towards unknown conclusions. As an example my daughter consistently wove in narratives around rain and thunderstorms as we made our drawings. She was often more interested in exploring meanings around rain and storms than the meanings the doll objects might offer. She also often expressed resistance to the activity by declaring that she was going to ‘rub the dolly off’ (the paper). She would rub her hands over the drawing to disrupt the image and my drawing of it. I cannot say whether this was to take my attention away from the activity or for some other purpose, but it often momentarily intercepted my focus in observing and drawing the dolls. Interestingly, the outcome of this was not annoyance. I was often interested in the effect this rubbing had on my drawing, and on many occasions it added a quality to the drawing that I would almost certainly have missed if drawing alone. This interception presented me with additional drawing methods. Likewise I often intercepted her drawing, adding marks, rubbing out, smudging, drawing over. Her reaction was often one of amusement or quite observation. I never observed frustration or anger at this, but that is possibly due to her happiness that we were doing something together. Our six doll drawings aren't pretty or sentimental because the doll images challenge cultural ideas of the niceness of motherhood, and of the precious baby. Meanings around mother/daughter identities that might have been attached to the dolls that we drew shifted as we collaborated. This shifting reflected the connections to other meanings that informed our respective undertaking of the act of drawing, and the tools and techniques we used to make our drawings. Our employment of multimodal communication tools (such as physical movement, spoken dialogue, singing, onomatopoeic sound effects) to construct the drawings exposed us to intersubjective and collective creating. For example, we used the same doll as object matter a number of times, but the thought references that were pulled on during the 9 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 construction of our drawings and the combination of physical drawing movements we used as we drew differed, being unrepeatable to/by either of us. We collaborated in being a mother/daughter in chaotic, “untimely ways” (Masny, 2005/2006, p. 151). On one occasion we worked a second drawing over an earlier drawing (figure 4). We re-engaged with a prior drawing and placed a new drawing over the initial one as we drew again. Our drawing was fluid rather than it being an end result (something that has reached stasis, something that has concluded). It briefly captured a moment of intersubjective communication between us. DESIRING AND BECOMING Deleuzian & Guattarian (1972/1983) concepts of desire surface when examining familial relationships of a mother and daughter through collaborative drawing. Our drawing process was driven by desire, driving our arms and tools into making marks and visualisations. We engaged in unconscious autoproduction, working outside our conscious bodies as ‘desiring machines’ (Deleuze 1969/1990), connecting to machines that drive other connected machines: hand, eye, thought, experience, with pencil, paper, charcoal. With the mind as machine we became body-less, working with the hand machine, pencil machine, paper machine. As desiring machines as we drew, we separately and constantly referenced other things that were unconnected and fragmented (Deleuze & Guattari 1972/1983). This fragmentation forced the drawings to progress in many unpredictable directions, prompting discovery about the ability to express and make a mark, to make experience, to have an imprint (on paper). RHIZOME AND INTERCEPTION Thinking of drawing as unconscious autoproduction that pulls on pre-existing references challenges the idea of knowledge as being self-constructed or original. As MacNaughton (2005) suggests, “we do not ‘make’ meaning; meaning is made external to us through how texts are constructed by their cultural histories.” (p. 89). Mother, daughter, doll references surrounded us during the production of our drawings. We encountered these influences as a rhizomatic network, like 'flat' maps of influences or “circles of converging series” (Deleuze, 1969/1990, p. 111) that we called upon during our drawing. Because the rhizomatic maps that swarmed around us were unpredictable, the references that surfaced were partial, dynamic, complex and multiple. They included snapshots of motherhood, daughterhood, gendered play, femininity, cultural norms, belonging and social success. Our interception of these and other references forced a sudden change of direction in the other drawer, to bring about unpredictable and mutable alterations and to challenge our familial adult/child power relationships. 10 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 Deconstructing these drawings helps to challenge conventions around children’s art practices, artist drawing practices, and conventional early childhood pedagogies that regard drawing as a precursor to writing. Reconstructing them helps to consider how drawings are able to convey interrelated meanings relating to the drawers’ culture/s and intention/s. I can deconstruct and reconstruct myself as participant, mother, researcher so that I may re-view our drawings, to challenge how my participant, mother, researcher subjectivities affects my “will to truth” (MacNaughton, 2005, p. 120), my assumptions and prejudices around each of these roles. Our drawings reference mother/daughter identities and mother/daughter intersubjectivities. Our drawing together connected us to networks of ideas that were undefined and undetermined at the outset, but gave us a shared experience of ‘becoming’ mother and daughter. CONCLUSION Intergenerational collaborative drawing is a socially just practice because it shifts power relationships, and in the context of this paper it exposed the conventions lurking in our mother/daughter subjectivities. Intergenerational collaborative drawing implements socially just practices in early childhood education contexts because it serves to unsettle the “development of quality teaching and innovation in teaching as a technocratic process where method matters.” (MacNaughton 2005, p. 194). Dominant beliefs around how to best teach young children prioritise pre-constructed chapters of achievement based upon a mono-cultural view of children. Despite the dominance of developmental theories, and the more recent persuasive shift towards sociocultural framings of what/how children learn or understand (Robbins, 2003; Rogoff, 2003; Vasquez, 2006; Vygotsky, 1978) ways of communicating in early childhood are needed that acknowledge and embrace diversity. There is a need to critique the cultural behaviours adults demonstrate to young children explicitly through the curriculum, and implicitly through pedagogy to provide early childhood educators with bridges to take them from acceptance to activism, or “truth to regimes of truth” (MacNaughton, 2005, p. 26). There is a need to challenge teaching skills that rotate around simplistic, universal perceptions of the child; critical questioning of such models is compounded however due to vastly differing education/training and face-to-face experiences of early childhood staff (Elliot, 2006). It is vital though to support early childhood professionals in gaining confidence to reject such models and practices and help them resist designing their activities around achieving measurable outcomes and exclusionary, normative assessment practices. The intergenerational collaborative drawing detailed in this paper contributes to pedagogical inquiry that seeks to subvert persistent, historicsed disocurses embedded in 11 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 early childhood that position the child as deeply self-identifying. This collaborative approach to drawing provided opportunities for reciprocity through multimodal dialogue as this mother and child drew together. Drawing seems an unlikely activity to affect change. It doesn't seem to align with any philosophical paradigm, as an activity it has been firmly rooted within the specific area of the fine/visual arts. Taking drawing out of the sole domain of arts practice and drawing collaboratively in relation to the whole curriculum fosters intersubjective connections that challenge deep-seated power structures embedded in discreet discipline-based pedagogies. When I began drawing with my daughter, it was difficult. I conceptualised about this project via my artist, mother, educator, and researcher subjectivities. The regimes of truth attached to these subjectivities came into play almost immediately as I began to work with her. For example, as an artist I was used to working individually, through solitary practice that requires me to independently apply knowledge to reach a structurally defined standard of artistic professionalism. Our initial drawing collaborations made me question all aspects of this practice, and particularly my artist subjectivity. Our drawing collaborations fundamentally challenged me to deconstruct and reconstruct my drawing practices and beliefs, to suspend what I had known to be ‘true’ and to be open to new ways of working. Over time, and with lots of exposure to the collaborative drawing process I began to fully enjoy this new approach to drawing, and to the shared construction of them with my daughter. Her subjectivities were eye opening to me. She shared in the process of deconstructing and then reconstructing, she helped me to examine my subjectivities as a researcher, and our mother/daughter intersubjectivities, to alert me to see how these are culturally constructed and upheld. I now find that I have difficulty in drawing by myself. I look forward to collaborating with her because she always surprises me and enriches my efforts through her responses to the media and stimulus. This expands on my own practices and understandings. I now struggle to make drawings that I like as much as those I produce with her. I see my own solitary efforts as less rich than those that she is involved with. I present this as a potent metaphor for deconstructing and reconstructing early childhood pedagogies. Initially it is difficult to challenge deep-seated beliefs about the child and how they learn, how they receive and process information, and the role the teacher/educator has in all that. Challenging such beliefs facilitates transition from discomfort to expansion, to use socially just pedagogies by challenging regimes of truth. I am filled with hope that it is possible to change these deep-seated beliefs and behaviours through something as simple as drawing together. 12 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 REFERENCES Bouza Koster, J. (2005) Growing artists: Teaching art to young children (3rd ed.). New York: Thompson Delmar Learning. Brakman, S-V, & Scholz, S. J. (2006) Adoption, ART, and a re-conception of the maternal body: Toward Embodied Maternity. Hypatia, 21(1), 54-73. Caldwell, H., & Moore, B. (1991) The art of writing: Drawing as preparation for narrative writing in the primary grades, Studies in Art Education 32(4), 207-219. Deleuze, G. (1969/1990) The logic of sense. New York: Columbia University Press. Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1972/1983) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Dobris, C. A., & White-Mills, K. (2006) Rhetorical visions of motherhood: A feminist analysis of the What to Expect series, Women and Language, 29(1), 29-36. Elliot, A. (2006) Early childhood education: Pathways to quality and equity for all children. Victoria: Australian Council for Educational Research. Gandini, L., Hill, L., Cadwell, L., & Schwall, C. (2005) In the spirit of the studio: Learning from the Atelier of Reggio Emilia. New York: Teachers College Press. Herberholz, B. & Hanson, L. (1995) Early childhood art (5th ed.). Boston, Mass: McGraw Hill. Lindstrom, M. (1957) Children’s art: A study of normal development in children’s modes of visualization. Berkeley: University of California Press. Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1975) Creative and mental growth. (6th Ed) New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. Mac Naughton, G. (2005) Doing Foucault in early childhood studies: Applying poststructural ideas. London: Routledge. Masny, D. (2005/2006) Learning and creative processes: a poststructural perspective on language and multiple literacies, International Journal of Learning, 12(5), 149-156. Olson, J. L. (1992) Envisioning writing. Portsmouth: Heinemann Educational Books Inc. Rich Sheridan, S. (2002) The neurological significance of children’s drawing: The scribble hypothesis, Journal of Visual Literacy, 22(2), 107-128. Richards, R. (2007) Outdated relics on hallowed ground, Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 32(4), 22-30. Robbins, J. (2003) The more he looked inside the more Piglet wasn’t there: What adopting a sociocultural perspective can help us see, The Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 26(2), 1-7. Rogoff, B. (2003) The cultural nature of human development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Schirrmacher, R. (2006) Art and creative development for young children (5th ed.). New York: Thompson Delmar Learning. 13 TRACEY | journal: Drawing Knowledge 2012 Stephens, J. (2004) Beyond binaries in motherhood research, Family Matters, 69(Spring/Summer), 88-93. Vasquez, O. A. (2006) Cross-national explorations of sociocultural research on learning, Review of Research in Education, 30(1), 33-64. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press. 14