Sailing_to_Byzantium

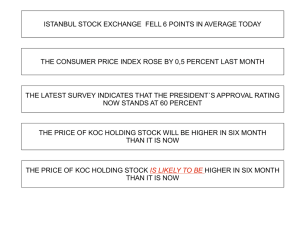

advertisement