Where Did All the Fish Go?

advertisement

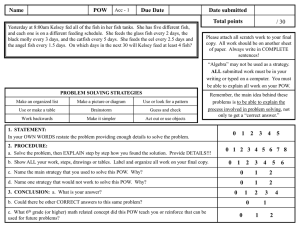

Bishopville Prong “Where did all the Fish Go? Stage 1 – Desired Results Content Standard(s): 5th Grade: 6.B.2.b 7th Grade: 6.A.1. a, 6.B.1.b 6th Grade: 6.A.1.c, 6.B.1.c 8th Grade: 6.B.1.a, 6.B.1.b Understanding (s)/goals Essential Question(s): Human use of resources have Example: negative and positive effects on local How are human choices and global ecosystems. impacting freshwater ecosystems? Student objectives (outcomes): Stage 2 – Assessment Evidence Performance Task(s): Other Evidence: Stage 3 – Learning Plan Learning Activities: Engage: Narrative Explore: Video Procedure: Debrief: See questions Explain: Bishopville Prong Background Information and maps. Evaluate: Exit ticket: Opening Narrative: Alt. High school scenario available below. Where did all the Fish Go? Jim and Lisa Taylor’s Grandpa rarely came home to the Eastern Shore of Maryland. When he does, they always go fishing. On this visit Grandpa Taylor wanted to take the kids to his hometown of Bishopville. There was a great spot where he fished as a young boy. He drove over the bridge into Bishopville and parked outside the old Rita’s Bakery shop. Jim and Lisa helped Grandpa Taylor unpack the fishing poles and bait and headed back towards the bridge. Grandpa Taylor scratched his head and said, “This area just don’t look the same. The water is cloudy. I used to be able to see all the way to the bottom.” The found a spot on the side of the bridge and cast their lines. They must have tried for at least half an hour. Nothing took their bait. Grandpa looked perplexed, “I always caught fish here. In fact, they almost jumped into our arms. If we didn’t catch fish we sure did catch eels. What happened to the fish? What happened to the eels?” Alt. Narrative A Fish Kill in Bishopville Prong A hot summer day can bring back memories. The quiet of still air raises thoughts of other days, and stories of summers long past. They say this summer is going to be hot, and that makes a lot of people worry. If you ask anyone in who remembers a few years back, they’ll tell you what happened. There were a lot of fish that died suddenly. That much everyone agrees with. What is less clear is why it happened. Some will say it was the hot weather that year. “The heat of mid-summer killed the fish,” some said. “It was something in the water—some sort of pollution,” others said. “The water in that pond is stagnant,” others offered. Still others said that it was the dam itself on the Bishopville Prong that had caused the fish to die. What everyone agreed to, though, was that a lot of fish had died and floated to the top of the pond made by the dam at Bishopville. It was an unpleasant sight, and an even more unpleasant smell. For anyone who liked to go fishing there, it was the end of a season that had not yet begun. The different reasons given were confusing. And they were worrisome. Could they all be true? Was one of the reasons right? Was it something else entirely? How could someone tell what had happened? How could someone find out, so something could be done to keep it from happening again. Bishopville Prong Background Bishopville Prong, a tidal tributary to the St. Martin River, in Bishopville Maryland, (see map) drains a watershed area of approximately 10,817 acres. The Bishopville Prong watershed land use consists of mixed agriculture (5,144 acres, 48%), forest and other herbaceous cover (3,774 acres, 35 %), urban (1,899 acres, 18 %). There are two major point source discharges of nutrients in the St. Martin River waters, the Ocean Pines Service Area Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), and Perdue Farms Inc. in Showell. In 1998, these sources were contributing about 36,566 lb/yr of nitrogen and 2,313 lb/yr of phosphorus to the St. Martin River and eventually to the Isle of Wight Bay. Source: http://www.epa.gov/reg3wapd/tmdl/MD_TMDLs/NorthernCoastalBays/NC B_main_final.pdf American Eel Connection When it comes to adaptability, few species can top the American eel. They turn up in more habitats than any other fish. After spawning in the open ocean, they can be found in coastal estuaries, rivers, trout streams, farm ponds—even wet caves. Eels spawn in the Sargasso Sea, and then die after mating once. Their larvae are carried by currents to the coast, where they migrate toward land, living most of their lives in freshwater streams. Those migrating far upstream tend to be exclusively female, and may remain in headwater areas for up to 30 years before returning to the Sargasso to spawn—filled with huge numbers of eggs. American eel populations have dropped so sharply that leading eel scientists issued a “declaration of concern” about American eels, as well as European and Japanese eels, which are also in decline. The USF&WS is reviewing a petition that the American eel be considered for protection under the federal Endangered Species Act. Contributing factors to the decline may include overfishing, loss of habitat, the introduction of an exotic parasite that infects the eels, and possibly even changes in the ocean currents that distribute eel larvae along the coast. Some of those factors—such as changes in currents—are beyond human control. Historically, eels were so abundant that they constituted more than 25 percent of fish biomass in freshwater streams. But the construction of dams and other fish blockages have restricted much of that habitat over the last century. Eels can wriggle out of the water and onto damp grass or wet rocks to bypass some obstructions. Source: http://www.bayjournal.com/newsite/article.cfm?article=2529 Project Summary The Bishopville Dam modification and stream restoration project is a cooperative effort among the Maryland Coastal Bays Program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, US Army Corps of Engineers to modify the dam at Bishopville to allow for fish passage, landscape the area using native vegetation, restore the stream and streamside vegetation and restore seepage wetlands at a nearby reclaimed sand/gravel mine. Dam modification will consist of retaining a portion of the current pond, maintaining water level at current pool elevation and constructing a series of grade control pools to allow fish to pass up the creek which will open about seven miles of stream habitat for fishes. Also, a nearby 30 acre abandoned sand/gravel mine, will be restored to forested wetland with plantings of cypress and white cedar, once a common species in the area, but now virtually absent from the coastal bays. In addition to opening the stream to fish passage, the project is designed to restore over 1,000 feet of coastal plain stream and approximately 12 acres of marsh and forest in the floodplain. Water quality benefits will result from habitat improvement through increased wetland area and improved function of the floodplain. Source: http://www.mdcoastalbays.org/archive/2007/dam-waterqualityfish-monitoring-plan3.pdf