{ This page and the next page consist of material provided by

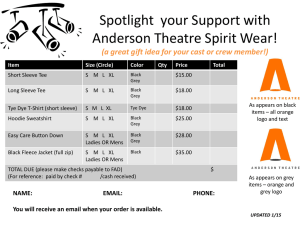

advertisement

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

1

{ This page and the next page consist of material provided by Professor Setear.

The excerpt from The Guns of August begins on page 3. }

From an international political viewpoint, the summer of 1914 saw Europe

plunged into crisis and then war. What was called “The Great War” at the time

would, with the unfortunate hindsight provided by the conflict that began just 25

years later, become known as “World War I.” From an international legal

viewpoint, the summer crisis and the outbreak of war involved not only the

system of alliances described at the end of the previous chapter but also Belgian

neutrality and the role of declarations of war.

The excerpt below consists of Chapters Six, Seven, Eight, and Nine from

The Guns of August. Together, these chapters comprise a section of the book

entitled “Outbreak.” The preceding section of the book, “Plans,” focused on the

plans of the armies of Germany, France, and Great Britain. Germany’s

“Schlieffen Plan” envisioned a sweeping movement through neutral Belgium in

order to outflank French forces and seize Paris. The Schlieffen Plan was designed

to win a quick victory for Germany in the West, thereby allowing Germany to turn

its attention to its eastern front before the slower-mobilizing troops of Russia

could threaten Prussia and the rest of Germany. The military plans of France

envisioned a rapidly mounted offensive against Germany to recapture the

provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, lost in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, and

continue the drive into historically German territory. Tactically as well as

strategically, the French were firmly committed to the virtues of offensive rather

than defensive action. The military plans of Britain eventually overcame a longstanding British hesitation to commit forces to the Continent and came to assume

the landing of a British Expeditionary Force in support of the French (and the

presence of English naval power in the English Channel while French fleets

concentrated on the Mediterranean)—despite the lack of a formal military alliance

between France and Great Britain.

2

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

The section of The Guns of August that follows “Outbreak” is entitled

“Battle.” That section covers the first battles of the war in Belgium and France

(and, to a lesser extent, in the East).

A note on the military technology of the early 20th century may be in order.

The American Civil War, fought between 1861 and 1865, is often called the first

“modern” war. Strategically, the American Civil War was a lengthy conflict

mobilizing the entire range of economic resources of the warring parties;

operationally, the war involved the large-scale use of railroads for troop

movements and the connection of field armies to their political leadership with

telegraph lines; tactically, the war saw the widespread use of rifled weapons by

infantrymen, which allowed foot soldiers to dominate the battlefield and

necessitated the dispersal of units to a degree vastly different from the close-order

formations of the Napoleonic era. The situation at the outset of World War I did

not appear to the parties to be greatly different from the situation prevailing at the

end of the American Civil War (although both sides believed that the trench

warfare that characterized the later stages of the American Civil War was an

anomaly). The use of railroads to bring troops to the front was the subject of

intricate plans by all sides, as was the mobilization of manpower resources from

peacetime occupations into military service. At the operational and tactical level,

railroads and marching by foot were the dominant methods of transport at the

outset of World War I . Motorized transport—trucks and cars, that is—was in its

infancy and was not integrated into main-line operational military units; the tank

had not yet been invented; and the airplane was a novelty thought to be useful, if

at all, for reconnaissance and communications. The later stages of the war would

see the introduction of the tank and the airplane into combat, and the dominance

of the battlefield by the machine gun, heavy artillery, and trenches. But at the

outset of the war, the participants viewed the conflict as likely to be decided by

the employment of rapidly mobilized masses of rifle-armed infantry transported to

the front by railroad and then proceeding on foot.

The Guns of August, by the way, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1963 for “best

non-fiction” book. (That same year, Maria Goeppert-Mayer became the first

woman to win the Nobel Prize for Physics since Madame Curie, and—on a plane

from Dallas, Texas to Washington, DC—Sarah Tilghman Hughes became the

first, and so far the only, woman to swear in a US President.)

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

THE GUNS OF AUGUST

Barbara W. Tuchman

Reproduced for Educational Purposes Only.

No Charge for Distribution.

Copyright © 1963 by Barbara W. Tuchman

3

4

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

OUTBREAK

“Some damned foolish thing in the Balkans,” Bismarck had predicted,

would ignite the next war. The assassination of the Austrian heir apparent,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, by Serbian nationalists on June 28, 1914, satisfied his

condition. Austria-Hungary, with the bellicose frivolity of senile empires,

determined to use the occasion to absorb Serbia as she had absorbed Bosnia and

Herzegovina in 1909. Russia on that occasion, weakened by the war with Japan,

had been forced to acquiesce by a German ultimatum followed by the Kaiser's

appearance in “shining armor,” as he put it, at the side of his ally, Austria. To

avenge that humiliation and for the sake of her prestige as the major Slav power,

Russia was now prepared to put on the shining armor herself. On July 5 Germany

assured Austria that she could count on Germany's “faithful support” if whatever

punitive action she took against Serbia brought her into conflict with Russia. This

was the signal that let loose the irresistible onrush of events. On July 23 Austria

delivered an ultimatum to Serbia, on July 26 rejected the Serbian reply (although

the Kaiser, now nervous, admitted that it “dissipates every reason for war”), on

July 28 declared war on Serbia, on July 29 bombarded Belgrade. On that day

Russia mobilized along her Austrian frontier and on July 30 both Austria and

Russia ordered general mobilization. On July 31 Germany issued an ultimatum to

Russia to demobilize within twelve hours and “make us a distinct declaration to

that effect.”

War pressed against every frontier. Suddenly dismayed, governments

struggled and twisted to fend it off. It was no use. Agents at frontiers were

reporting every cavalry patrol as a deployment to beat the mobilization gun.

General staffs, goaded by their relentless timetables, were pounding the table for

the signal to move lest their opponents gain an hour's head start. Appalled upon

the brink, the chiefs of state who would be ultimately responsible for their

country's fate attempted to back away but the pull of military schedules dragged

them forward.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

5

CHAPTER SIX—AUGUST 1: BERLIN

At noon on Saturday, August 1, the German ultimatum to Russia expired

without a Russian reply. Within an hour a telegram went out to the German

ambassador in St. Petersburg instructing him to declare war by five o’clock that

afternoon. At five o’clock the Kaiser decreed general mobilization, some

preliminaries having already got off to a head start under the declaration of

Kriegesgefahr (Danger of War) the day before. At five-thirty Chancellor

Bethmann-Hollweg, absorbed in a document he was holding in his hand and

accompanied by little Jagow, the Foreign Minister, hurried down the steps of the

Foreign Office, hailed an ordinary taxi, and sped off to the palace. Shortly

afterward General von Moltke, the gloomy Chief of General Staff, was pulled up

short as he was driving back to his office with the mobilization order signed by

the Kaiser in his pocket. A messenger in another car overtook him with an urgent

summons from the palace. He returned to hear a last-minute, desperate proposal

from the Kaiser that reduced Moltke to tears and could have changed the history

of the twentieth century.

Now that the moment had come, the Kaiser suffered at the necessary risk

to East Prussia, in spite of the six weeks’ leeway his Staff promised before the

Russians could fully mobilize. “I hate the Slavs,” he confessed to an Austrian

officer. “I know it is a sin to do so. We ought not to hate anyone. But I can’t help

hating them.” He had taken comfort, however, in the news, reminiscent of 1905,

of strikes and riots in St. Petersburg, of mobs smashing windows, and “violent

street fights between revolutionaries and police.” Count Pourtalès his aged

ambassador, who had been seven years in Russia, concluded, and repeatedly

assured his government, that Russia would not fight for fear of revolution. Captain

von Eggeling, the German military attaché, kept repeating the credo about 1916,

and when Russia nevertheless mobilized, he reported she planned “no tenacious

offensive but a slow retreat as in 1812.” In the affinity for error of German

diplomats, these judgments established a record. They gave heart to the Kaiser,

who as late as July 31 composed a missive for the “guidance” of his Staff,

rejoicing in the “mood of a sick Tom-cat” that, on the evidence of his envoys, he

said prevailed in the Russian court and army.

6

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

In Berlin on August 1, the crowds milling in the streets and massed in

thousands in front of the palace were tense and heavy with anxiety. Socialism,

which most of Berlin’s workers professed, did not run so deep as their instinctive

fear and hatred of the Slavic hordes. Although they had been told by the Kaiser, in

his speech from the balcony announcing Kriegesgefahr the evening before, that

the “sword has been forced into our hand,” they still waited in the ultimate dim

hope of a Russian reply. The hour of the ultimatum passed. A journalist in the

crowd felt the air “electric with rumor. People told each other Russia had asked

for an extension of time. The Bourse writhed in panic. The afternoon passed in

almost insufferable anxiety.” Bethmann-Hollweg issued a statement ending, “If

the iron dice roll, may God help us.” At five o’clock a policeman appeared at the

palace gate and announced mobilization to the crowd, which obediently struck up

the national hymn, “Now thank we all our God.” Cars raced down Unter den

Linden with officers standing up in them, waving handkerchiefs and shouting,

“Mobilization!” Instantly converted from Marx to Mars, people cheered wildly

and rushed off to vent their feelings on suspected Russian spies, several of whom

were pummeled or trampled to death in the course of the next few days.

Once the mobilization button was pushed, the whole vast machinery for

calling up, equipping, and transporting two million men began turning

automatically. Reservists went to their designated depots, were issued uniforms,

equipment, and arms, formed into companies and companies into battalions, were

joined by cavalry, cyclists, artillery, medical units, cook wagons, blacksmith

wagons, even postal wagons, moved according to prepared railway timetables to

concentration points near the frontier where they would be formed into divisions,

divisions into corps, and corps into armies ready to advance and fight. One army

corps alone—out of the total of 40 in the German forces—required 170 railway

cars for officers, 965 for infantry, 2,960 for cavalry, 1,915 for artillery and supply

wagons, 6,010 in all, grouped in 140 trains and an equal number again for their

supplies. From the moment the order was given, everything was to move at fixed

times according to a schedule precise down to the number of train axles that

would pass over a given bridge within a given time.

Confident in his magnificent system, Deputy Chief of Staff General

Waldersee had not even returned to Berlin at the beginning of the crisis but had

written to Jagow: “I shall remain here ready to jump; we are all prepared at the

General Staff, in the meantime there is nothing for us to do.” It was a proud

tradition inherited from the elder, or “great,” Moltke who on mobilization day in

1870 was found lying on a sofa reading Lady Audley’s Secret.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

7

His enviable calm was not present today in the palace. Face to face no

longer with the specter but the reality of a two-front war, the Kaiser was as close

to the “sick Tom-cat” mood as he thought the Russians were. More cosmopolitan

and more timid than the archetype Prussian, he had never actually wanted a

general war. He wanted greater power, greater prestige, above all more authority

in the world’s affairs for Germany but he preferred to obtain them by frightening

rather than by fighting other nations. He wanted the gladiator’s rewards without

the battle, and whenever the prospect of battle came too close, as at Algeciras and

Agadir, he shrank.

As the final crisis boiled, his marginalia on telegrams grew more and more

agitated: “Aha! the common cheat,” “Rot!” “He lies!” “Mr. Grey is a false dog,”

“Twaddle!” “The rascal is crazy or an idiot!” When Russia mobilized he burst

into a tirade of passionate foreboding, not against the Slav traitors but against the

unforgettable figure of the [Kaiser’s late] wicked uncle[, Edward VII, King of

England]: “The world will be engulfed in the most terrible of wars, the ultimate

aim of which is the ruin of Germany. England, France and Russia have conspired

for our annihilation ... that is the naked truth of the situation which was slowly but

surely created by Edward VII. ... The encirclement of Germany is at last an

accomplished fact. We have run our heads into the noose ... The dead Edward is

stronger than the living I!”

Conscious of the shadow of the dead Edward, the Kaiser would have

welcomed any way out of the commitment to fight both Russia and France and,

behind France, the looming figure of still-undeclared England.

....

In Berlin just after five o’clock a telephone rang in the Foreign Office.

Under-Secretary Zimmermann, who answered it, turned to the editor of the

Berliner Tageblatt sitting by his desk and said, “Moltke wants to know whether

things can start.” At that moment a telegram from London, just decoded, broke in

upon the planned proceedings. It offered hope that if the movement against France

could be instantly stopped Germany might safely fight a one-front war after all.

Carrying it with them, Bethmann and Jagow dashed off on their taxi trip to the

palace.

8

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

The telegram, from Prince Lichnowsky, [the German] ambassador in

London, reported an English offer, as Lichnowsky understood it, “that in case we

did not attack France, England would remain neutral and would guarantee

France’s neutrality.”

The ambassador belonged to that class of Germans who spoke English and

copied English manners, sports, and dress, in a strenuous endeavor to become the

very pattern of an English gentleman. His fellow noblemen, the Prince of Pless,

Prince Blucher, and Prince Munster were all married to English wives. At a dinner

in Berlin in 1911, in honor of a British general, the guest of honor was astonished

to find that all forty German guests, including Bethmann-Hollweg and Admiral

Tirpitz, spoke English fluently. Lichnowsky differed from his class in that he was

not only in manner but in heart an earnest Anglophile. He had come to London

determined to make himself and his country liked. English society had been lavish

with country weekends. To the ambassador no tragedy could be greater than war

between the country of his birth and the country of his heart, and he was grasping

at any handle to avert it.

When the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, telephoned him that

morning, in the interval of a Cabinet meeting, Lichnowsky, out of his own

anxiety, interpreted what Grey said to him as an offer by England to stay neutral

and to keep France neutral in a Russo-German war, if, in return, Germany would

promise not to attack France.

Actually, Grey had not said quite that. What, in his elliptical way, he

offered was a promise to keep France neutral if Germany would promise to stay

neutral as against France and Russia, in other words, not go to war against either,

pending the result of efforts to settle the Serbian affair. After eight years as

Foreign Secretary in a period of chronic “Bosnias,” as Bülow called them, Grey

had perfected a manner of speaking designed to convey as little meaning as

possible; his avoidance of the point-blank, said a colleague, almost amounted to

method. Over the telephone, Lichnowsky, himself dazed by the coming tragedy,

would have had no difficulty misunderstanding him.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

9

The Kaiser clutched at Lichnowsky’s passport to a one-front war. Minutes

counted. Already mobilization was rolling inexorably toward the French frontier.

The first hostile act, seizure of a railway junction in Luxembourg, whose

neutrality the five Great Powers, including Germany, had guaranteed, was

scheduled within an hour. It must be stopped, stopped at once. But how? Where

was Moltke? Moltke had left the palace. An aide was sent off, with siren

screaming, to intercept him. He was brought back.

The Kaiser was himself again, the All-Highest, the War Lord, blazing with

a new idea, planning, proposing, disposing. He read Moltke the telegram and said

in triumph: “Now we can go to war against Russia only. We simply march the

whole of our Army to the East!”

Aghast at the thought of his marvelous machinery of mobilization

wrenched into reverse, Moltke refused point-blank. For the past ten years, first as

assistant to Schlieffen, then as his successor, Moltke’s job had been planning for

this day, The Day, Der Tag, for which all Germany’s energies were gathered, on

which the march to final mastery of Europe would begin. It weighed upon him

with an oppressive, almost unbearable responsibility.

Tall, heavy, bald, and sixty-six years old, Moltke habitually wore an

expression of profound distress which led the Kaiser to call him der traurige

Julius (or what might be rendered “Gloomy Gus”; in fact, his name was

Helmuth). Poor health, for which he took an annual cure at Carlsbad, and the

shadow of a great uncle were perhaps cause for gloom. From his window in the

red brick General Staff building on the Königplatz where he lived as well as

worked, he looked out every day on the equestrian statue of his namesake, the

hero of 1870 and, together with Bismarck, the architect of the German Empire.

The nephew was a poor horseman with a habit of falling off on staff rides and,

worse, a follower of Christian Science with a side interest in anthroposophism and

other cults. For this unbecoming weakness in a Prussian officer he was considered

“soft”; what is more, he painted, played the cello, carried Goethe’s Faust in his

pocket, and had begun a translation of Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande.

Introspective and a doubter by nature, he had said to the Kaiser upon his

appointment in 1906: “I do not know how I shall get on in the event of a

campaign. I am very critical of myself.” Yet he was neither personally nor

politically timid. In 1911, disgusted by Germany’s retreat in the Agadir crisis, he

10

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

wrote to Conrad von Hötzendorff that if things got worse he would resign,

propose to disband the army and “place ourselves under the protection of Japan;

then we can make money undisturbed and turn into imbeciles.” He did not hesitate

to talk back to the Kaiser, but told him “quite brutally” in 1900 that his Peking

expedition was a “crazy adventure,” and when offered the appointment as Chief of

Staff, asked the Kaiser if he expected “to win the big prize twice in the same

lottery”—a thought that had certainly influenced William’s choice. He refused to

take the post unless the Kaiser stopped his habit of winning all the war games

which was making nonsense of maneuvers. Surprisingly, the Kaiser meekly

obeyed.

Now, on the climactic night of August 1, Moltke was in no mood for any

more of the Kaiser’s meddling with serious military matters, or with meddling of

any kind with the fixed arrangements. To turn around the deployment of a million

men from west to east at the very moment of departure would have taken a more

iron nerve than Moltke disposed of. He saw a vision of the deployment crumbling

apart in confusion, supplies here, soldiers there, ammunition lost in the middle,

companies without officers, divisions without staffs, and those 11,000 trains, each

exquisitely scheduled to click over specified tracks at specified intervals of ten

minutes, tangled in a grotesque ruin of the most perfectly planned military

movement in history.

“Your Majesty,” Moltke said to him now, “it cannot be done. The

deployment of millions cannot be improvised. If Your Majesty insists on leading

the whole army to the East it will not be an army ready for battle but a

disorganized mob of armed men with no arrangements for supply. Those

arrangements took a whole year of intricate labor to complete”—and Moltke

closed upon that rigid phrase, the basis for every major German mistake, the

phrase that launched the invasion of Belgium and the submarine war against the

United States, the inevitable phrase when military plans dictate policy—“and once

settled, it cannot be altered.”

In fact it could have been altered. The German General Staff, though

committed since 1905 to a plan of attack upon France first, had in their files,

revised each year until 1913, an alternative plan against Russia with all the trains

running eastward.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

11

“Build no more fortresses, build railways,” ordered the elder Moltke who

had laid out his strategy on a railway map and bequeathed the dogma that railways

are the key to war. In Germany the railway system was under military control with

a staff officer assigned to every line; no track could be laid or changed without

permission of the General Staff. Annual mobilization war games kept railway

officials in constant practice and tested their ability to improvise and divert traffic

by telegrams reporting lines cut and bridges destroyed. The best brains produced

by the War College, it was said, went into the railway section and ended up in

lunatic asylums.

When Moltke’s “It cannot be done” was revealed after the war in his

memoirs, General von Staab, Chief of the Railway Division, was so incensed by

what he considered a reproach upon his bureau that he wrote a book to prove it

could have been done. In pages of charts and graphs he demonstrated how, given

notice on August 1, he could have deployed four out of the seven armies to the

Eastern Front by August 15, leaving three to defend the West. Matthias Erzberger,

the Reichstag deputy and leader of the Catholic Centrist Party, has left another

testimony. He says that Moltke himself, within six months of the event, admitted

to him that the assault on France at the beginning was a mistake and instead, “the

larger part of our army ought first to have been sent East to smash the Russian

steam roller, limiting operations in the West to beating off the enemy’s attack on

our frontier.”

On the night of August 1, Moltke, clinging to the fixed plan, lacked the

necessary nerve. “Your uncle would have given me a different answer,” the Kaiser

said to him bitterly. The reproach “wounded me deeply,” Moltke wrote afterward;

“I never pretended to be the equal of the old Field Marshal.” Nevertheless he

continued to refuse. “My protest that it would be impossible to maintain peace

between France and Germany while both countries were mobilized made no

impression. Everybody got more and more excited and I was alone in my

opinion.”

12

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

Finally, when Moltke convinced the Kaiser that the mobilization plan

could not be changed, the group which included Bethmann and Jagow drafted a

telegram to England regretting that Germany’s advance movements toward the

French border “can no longer be altered,” but offering a guarantee not to cross the

border before August 3 at 7:00 P.M., which cost them nothing as no crossing was

scheduled before that time. Jagow rushed off a telegram to his ambassador in

Paris, where mobilization had already been decreed at four o’clock, instructing

him helpfully to “please keep France quiet for the time being.” The Kaiser added a

personal telegram to King George, telling him that for “technical reasons”

mobilization could not be countermanded at this late hour, but “If France offers

me neutrality which must be guaranteed by the British fleet and army, I shall of

course refrain from attacking France and employ my troops elsewhere. I hope

France will not become nervous.”

It was now minutes before seven o’clock, the hour when the 16th Division

was scheduled to move into Luxembourg. Bethmann excitedly insisted that

Luxembourg must not be entered under any circumstances while waiting for the

British answer. Instantly the Kaiser, without asking Moltke, ordered his aide-decamp to telephone and telegraph 16th Division Headquarters at Trier to cancel the

movement. Moltke saw ruin again. Luxembourg’s railways were essential for the

offensive through Belgium against France. “At that moment,” his memoirs say, “I

thought my heart would break.”

Despite all his pleading, the Kaiser refused to budge. Instead, he added a

closing sentence to his telegram to King George, “The troops on my frontier are in

the act of being stopped by telephone and telegraph from crossing into France,” a

slight if vital twist of the truth, for the Kaiser could not acknowledge to England

that what he had intended and what was being stopped was the violation of a

neutral country. It would have implied his intention also to violate Belgium,

which would have been casus belli in England, and England’s mind was not yet

made up.

“Crushed,” Moltke says of himself, on what should have been the

culminating day of his career, he returned to the General Staff and “burst into

bitter tears of abject despair.” When his aide brought him for his signature the

written order canceling the Luxembourg movement, “I threw my pen down on the

table and refused to sign.” To have signed as the first order after mobilization one

that would have annulled all the careful preparations would have been taken, he

knew, as evidence of “hesitancy and irresolution.” “Do what you want with this

telegram,” he said to his aide; “I will not sign it.”

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

13

He was still brooding at eleven o’clock when another summons came from

the palace. Moltke found the Kaiser in his bedroom, characteristically dressed for

the occasion, with a military overcoat over his nightshirt. A telegram had come

from Lichnowsky, who, in a further talk with Grey, had discovered his error and

now wired sadly, “A positive proposal by England is, on the whole, not in

prospect.”

“Now you can do what you like,” said the Kaiser, and went back to bed.

Moltke, the Commander in Chief who had now to direct a campaign that would

decide the fate of Germany, was left permanently shaken. “That was my first

experience of the war,” he wrote afterward. “I never recovered from the shock of

this incident. Something in me broke and I was never the same thereafter.”

Neither was the world, he might have added. The Kaiser’s telephone order

to Trier had not arrived in time. At seven o’clock, as scheduled, the first frontier

of the war was crossed, the distinction going to an infantry company of the 69th

Regiment under command of a certain Lieutenant Feldmann. Just inside the

Luxembourg border, on the slopes of the Ardennes about twelve miles from

Bastogne in Belgium, stood a little town known to the Germans as Ulflingen.

Around it cows grazed on the hillside pastures; on its steep, cobblestone streets

not a stray wisp of hay, even in August harvest time, was allowed to offend the

strict laws governing municipal cleanliness in the Grand Duchy. At the foot of the

town was a railroad station and telegraph office where the lines from Germany

and Belgium crossed. This was the German objective which Lieutenant

Feldmann’s company, arriving in automobiles, duly seized.

With their relentless talent for the tactless, the Germans chose to violate

Luxembourg at a place whose native and official name was Trois Vierges. The

three virgins in fact represented faith, hope, and charity, but History with her

apposite touch arranged for the occasion that they should stand in the public mind

for Luxembourg, Belgium, and France.

14

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

At 7:30 a second detachment in automobiles arrived (presumably in

response to the Kaiser’s message) and ordered off the first group, saying “a

mistake had been made.” In the interval Luxembourg’s Minister of State Eyschen

had already telegraphed the news to London, Paris, and Brussels and a protest to

Berlin. The three virgins had made their point. By midnight Moltke had rectified

the reversal, and by the end of the next day, August 2, M-1 on the German

schedule, the entire Grand Duchy was occupied.

A question has haunted the annals of history ever since: What Ifs might

have followed if the Germans had gone east in 1914 while remaining on the

defensive against France? General von Staab showed that to have turned against

Russia was technically possible. But whether it would have been temperamentally

possible for the Germans to have refrained from attacking France when Der Tag

came is another matter.

********************

At seven o’clock in St. Petersburg, at the same hour when the Germans

entered Luxembourg, Ambassador Pourtalès, his watery blue eyes red-rimmed, his

white goatee quivering, presented Germany’s declaration of war with shaking

hand to Sazonov, the Russian Foreign Minister.

“The curses of the nations will be upon you!” Sazonov exclaimed.

“We are defending our honor,” the German ambassador replied.

“Your honor was not involved. But there is a divine justice.”

“That’s true,” and muttering, “a divine justice, a divine justice,” Pourtalès

staggered to the window, leaned against it, and burst into tears. “So this is the end

of my mission,” he said when he could speak. Sazonov patted him on the

shoulder, they embraced, and Pourtalès stumbled to the door, which he could

hardly open with a trembling hand, and went out, murmuring, “Goodbye,

goodbye.”

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

15

This affecting scene comes down to us as recorded by Sazonov with

artistic additions by the French ambassador Paléologue, presumably from what

Sazonov told him. Pourtalès reported only that he asked three times for a reply to

the ultimatum and after Sazonov answered negatively three times, “I handed over

the note as instructed.”

Why did it have to be handed over at all? Admiral von Tirpitz, the Naval

Minister, had plaintively asked the night before when the declaration of war was

being drafted. Speaking, he says, “more from instinct than from reason,” he

wanted to know why, if Germany did not plan to invade Russia, was it necessary

to declare war and assume the odium of the attacking party? His question was

particularly pertinent because Germany’s object was to saddle Russia with war

guilt in order to convince the German people that they were fighting in selfdefense and especially in order to keep Italy tied to her engagements under the

Triple Alliance.

Italy was obliged to join her allies only in a defensive war and, already

shaky in her allegiance, was widely expected to sidle out through any loophole

that opened up. Bethmann was harassed by this problem. If Austria persisted in

refusing any or all Serbian concessions, he warned, “it will scarcely be possible to

place the guilt of a European conflagration on Russia” and would “place us in the

eyes of our own people, in an untenable position.” He was hardly heard. When

mobilization day came, German protocol required that war be properly declared.

Jurists of the Foreign Office, according to Tirpitz. insisted it was legally the

correct thing to do. “Outside Germany,” he says pathetically, “there is no

appreciation of such ideas.”

In France appreciation was keener than he knew.

16

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

CHAPTER SEVEN—AUGUST 1: PARIS AND LONDON

One prime objective governed French Policy: to enter the war with

England as an ally. To ensure that event and enable her friends in England to

overcome the inertia and reluctance within their own Cabinet and country, France

had to leave it clear beyond question who was the attacked and who the attacker.

The physical act and moral odium of aggression must be left squarely upon

Germany. Germany was expected to do her part, but lest any overanxious French

patrols or frontier troops stepped over the border, the French government took a

daring and extraordinary step. On July 30 it ordered a ten-kilometer withdrawal

along the entire frontier with Germany from Switzerland to Luxembourg.

....

Withdrawal was a bitter gesture to ask of a French Commander in Chief

schooled in the doctrine of offensive and nothing but the offensive. It could have

shattered General Joffre as Moltke’s first experience of the war shattered him, but

General Joffre’s heart did not break.

From the moment of the President’s and Premier’s return, Joffre had been

hounding the government for the order to mobilize or at least take the preliminary

steps: recall of furloughs, of which many had been granted for the harvest, and

deployment of covering troops to the frontier. He deluged them with intelligence

reports of German pre-mobilization measures already taken. He loomed large in

authority before a new-born Cabinet, the tenth in five years, whose predecessor

had lasted three days. The present one was remarkable chiefly for having most of

France’s strong men outside it. Briand, Clemenceau, Caillaux, all former

premiers, were in opposition. Viviani, by his own evidence, was in a state of

“frightful nervous tension” which, according to Messimy, who was once again

War Minister, “became a permanent condition during the month of August.” The

Minister of Marine, Dr. Gauthier, a doctor of medicine shoved into the naval post

when a political scandal removed his predecessor, was so overwhelmed by events

that he “forgot” to order fleet units into the Channel and had to be replaced by the

Minister of Public Instruction on the spot.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

17

In the President, however, intelligence, experience, and strength of

purpose, if not constitutional power, were combined. Poincaré was a lawyer,

economist, and member of the Academy, a former Finance Minister who had

served as Premier and Foreign Minister in 1912 and had been elected President of

France in January, 1913. Character begets power, especially in hours of crisis, and

the untried Cabinet leaned willingly on the abilities and strong will of the man

who was constitutionally a cipher. Born in Lorraine, Poincaré could remember as

a boy of ten the long line of spiked German helmets marching through Bar-leDuc, his home town. He was credited by the Germans with the most bellicose

intent, partly because, as Premier at the time of Agadir, he had held firm, partly

because as President he had used his influence to push through the Three-Year

Military Service Law in 1913 against violent Socialist opposition. This and his

cold demeanor, his lack of flamboyance, his fixity, did not make for popularity at

home. Elections were going against the government, the Three-Year Law was near

to being thrown out, labor troubles and farmers’ discontent were rife, July had

been hot, wet, and oppressive with windstorms and summer thunder, and Mme.

Caillaux who had shot the editor of Figaro was on trial for murder. Each day of

the trial revealed new and unpleasant irregularities in finance, the press, the

courts, the government.

One day the French woke up to find Mme. Caillaux on page two—and the

sudden, awful knowledge that France faced war. In that most passionately

political and quarrelsome of countries one sentiment thereupon prevailed.

Poincaré and Viviani, returning from Russia, drove through Paris to the sound of

one prolonged cry, repeated over and over, “Vive la France!”

Joffre told the government that if he was not given the order to assemble

and transport the covering troops of five army corps and cavalry toward the

frontier, the Germans would “enter France without firing a shot.” He accepted the

ten-kilometer withdrawal of troops already in position less from subservience to

the civil arm—Joffre was about as subservient by nature as Julius Caesar—as

from a desire to bend all the force of his argument upon the one issue of the

covering troops. The government, still reluctant while diplomatic offers and

counter-offers flashing over the wires might yet produce a settlement, agreed to

give him a “reduced” version, that is, without calling out the reservists.

18

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

At 4:30 next day, July 31, a banking friend in Amsterdam telephoned

Messimy the news of the German Kriegesgefahr, officially confirmed an hour

later from Berlin. It was “une forme hypocrite de la mobilisation,” Messimy

angrily told the Cabinet. His friend in Amsterdam had said war was certain and

Germany was ready for it, “from the Emperor down to the last Fritz.” Following

hard upon this news came a telegram from Paul Cambon, French ambassador in

London, reporting that England was “tepid.” Cambon had devoted every day of

the past sixteen years at his post to the single end of ensuring England’s active

support when the time came, but he had now to wire that the British government

seemed to be awaiting some new development. The dispute so far was of “no

interest to Great Britain.”

Joffre arrived, with a new memorandum on German movements, to insist

upon mobilization. He was permitted to send his full “covering order” but no

more, as news had also come of a last-minute appeal from the Czar to the Kaiser.

The Cabinet continued sitting, with Messimy champing in impatience at the

“green baize routine” which stipulated that each minister must speak in turn.

At seven o’clock in the evening Baron von Schoen, making his eleventh

visit to the French Foreign Office in seven days, presented Germany’s demand to

know what course France would take and said he would return next day at one

o’clock for an answer. Still the Cabinet sat and argued over financial measures,

recall of Parliament, declaration of a state of siege, while all Paris waited in

suspense. One crazed young man cracked under the agony, held a pistol against a

café window, and shot dead Jean Jaurès, whose leadership in international

socialism and in the fight against the Three-Year Law had made him, in the eyes

of superpatriots, a symbol of pacifism.

A white-faced aide broke in upon the Cabinet at nine o’clock with the

news. Jaurès killed! The event, pregnant with possible civil strife, stunned the

Cabinet. Street barricades, riot, even revolt became a prospect on the threshold of

war. Ministers reopened the heated argument whether to invoke Carnet B, the list

of known agitators, anarchists, pacifists, and suspected spies who were to be

arrested automatically upon the day of mobilization. Both the Prefect of Police

and former Premier Clemenceau had advised the Minister of Interior, M. Malvy,

to enforce Carnet B. Viviani and others of his colleagues, hoping to preserve

national unity, were opposed to it. They held firm. Some foreigners suspected of

being spies were arrested, but no Frenchmen. In case of riot, troops were alerted

that night, but next morning there was only deep grief and deep quiet. Of the

2,501 persons listed in Carnet B, 80 per cent were ultimately to volunteer for

military service.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

19

At 2:00 A.M. that night, President Poincaré was awakened in bed by the

irrepressible Russian ambassador, Isvolsky, a former hyperactive foreign minister.

“Very distressed and very agitated,” he wanted to know, “What is France going to

do?”

Isvolsky had no doubts of Poincaré’s attitude, but he and other Russian

statesmen were always haunted by the fear that when the time came the French

Parliament, which had never been told the terms of the military alliance with

Russia, would fail to ratify it. The terms specifically stated, “If Russia is attacked

by Germany or by Austria supported by Germany, France will use all her available

forces to attack Germany.” As soon as either Germany or Austria mobilized,

“France and Russia, without previous agreement being necessary, shall mobilize

all their forces immediately and simultaneously and shall transport them as near

the frontiers as possible.... These forces shall begin complete action with all speed

so that Germany will have to fight at the same time in the East and in the West.”

These terms appeared unequivocal but, as Isvolsky had anxiously queried

Poincaré in 1912, would the French Parliament recognize the obligation? In

Russia the Czar’s power was absolute, so that France “may be sure of us,” but “in

France the Government is impotent without Parliament. Parliament does not know

the text of 1892. ... What guarantee have we that your Parliament would follow

your Government’s lead?”

“If Germany attacked,” Poincaré had replied on that earlier occasion,

Parliament would follow the Government “without a doubt.”

Now, facing Isvolsky again in the middle of the night, Poincaré assured

him that a Cabinet would be called within a few hours to supply the answer. At

the same hour the Russian military attaché in full diplomatic dress appeared in

Messimy’s bedroom to pose the same question. Messimy telephoned to Premier

Viviani who, though exhausted by the night’s events, had not yet gone to bed.

“Good God!” he exploded, “these Russians are worse insomniacs than they are

drinkers,” and he excitedly recommended “Du calme, du calme et encore du

calme!”

Pressed by the Russians to declare themselves, and by Joffre to mobilize,

yet held to a standstill by the need to prove to England that France would act only

20

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

in self-defense, the French government found calm not easy. At 8:00 next

morning, August 1, Joffre came to the War Office in the Rue St. Dominique to

beg Messimy, in “a pathetic tone that contrasted with his habitual calm,” to pry

mobilization from the government. He named four o’clock as the last moment

when the order could reach the General Post Office for dispatch by telegraph

throughout France in time for mobilization to begin at midnight. He went with

Messimy to the Cabinet at 9:00 A.M. and presented an ultimatum of his own:

every further delay of twenty-four hours before general mobilization would mean

a fifteen- to twenty-kilometer loss of territory, and he would refuse to take the

responsibility as Commander. He left, and the Cabinet faced the problem.

Poincaré was for action; Viviani, representing the antiwar tradition, still hoped

that time would provide a solution. At 11:00 he was called to the Foreign Office

to see von Schoen who in his own anxiety had arrived two hours early for the

answer to Germany’s question of the previous day: whether France would stay

neutral in a Russo-German war. “My question is rather naïve,” said the unhappy

ambassador, “for we know you have a treaty of alliance.”

“Evidemment,” replied Viviani, and gave the answer prearranged between

him and Poincaré. “France will act in accordance with her interests.” As Schoen

left, Isvolsky rushed in with news of the German ultimatum to Russia. Viviani

returned to the Cabinet, which at last agreed upon mobilization. The order was

signed and given to Messimy, but Viviani, still hoping for some saving

development to turn up within the few remaining hours, insisted that Messimy

keep it in his pocket until 3:30. At the same time the ten-kilometer withdrawal

was reaffirmed. Messimy telephoned it that evening personally to corps

commanders: “By order of the President of the Republic, no unit of the army, no

patrol, no reconnaissance, no scout, no detail of any kind, shall go east of the line

laid down. Anyone guilty of transgressing will be liable to court-martial.” A

particular warning was added for the benefit of the XXth Corps, commanded by

General Foch, of whom it was reliably reported that a squadron of cuirassiers had

been seen “nose to nose” with a squadron of Uhlans.

At 3:30, as arranged, General Ebener of Joffre’s staff, accompanied by two

officers, came to the War Office to call for the mobilization order. Messimy

handed it over in dry-throated silence. “Conscious of the gigantic and infinite

results to spread from that little piece of paper, all four of us felt our hearts

tighten.” He shook hands with each of the three officers, who saluted and departed

to deliver the order to the Post Office.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

21

At four o’clock the first poster appeared on the walls of Paris (at the comer

of the Place de la Concorde and the Rue Royale, one still remains, preserved

under glass). At Armenonville, rendezvous of the haut-monde in the Bois de

Boulogne, tea dancing suddenly stopped when the manager stepped forward,

silenced the orchestra, and announced: “Mobilization has been ordered. It begins

at midnight. Play the ‘Marseillaise.”’ In town the streets were already emptied of

vehicles requisitioned by the War Office. Groups of reservists with bundles and

farewell bouquets of flowers were marching off to the Gare de l’Est, as civilians

waved and cheered. One group stopped to lay its flowers at the feet of the blackdraped statue of Strasbourg in the Place de la Concorde. The crowds wept and

cried “Vive I’Alsace!” and tore off the mourning she had worn since 1870.

Orchestras in restaurants played the French, Russian, and British anthems. “To

think these are all being played by Hungarians,” someone remarked. The playing

of their anthem, as if to express a hope, made Englishmen in the crowd

uncomfortable and none more so than Sir Francis Bertie, the pink and plump

British ambassador who in a gray frock coat and gray top hat, holding a green

parasol against the sun, was seen entering the Quai d’Orsay. Sir Francis felt “sick

at heart and ashamed.” He ordered the gates of his embassy closed, for, as he

wrote in his diary, “though it is ‘Vive l’Angleterre’ today, it may be ‘Perfide

Albion’ tomorrow.”

********************

In London that thought hung heavily in the room where small, whitebearded M. Cambon confronted Sir Edward Grey. When Grey said to him that

some “new development” must be awaited because the dispute between Russia,

Austria, and Germany concerned a matter “of no interest” to Great Britain,

Cambon let a glint of anger penetrate his impeccable tact and polished dignity.

Was England “going to wait until French territory was invaded before

intervening?” he asked, and suggested that if so her help might be “very belated.”

Grey, behind his tight mouth and Roman nose, was in equal anguish. He

believed fervently that England’s interests required her to support France; he was

prepared, in fact, to resign if she did not; he believed events to come would force

her hand, but as yet he could say nothing officially to Cambon. Nor had he the

knack of expressing himself unofficially. His manner, which the English public,

22

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

seeing in him the image of the strong, silent man, found comforting, his foreign

colleagues found “icy.” He managed only to express edgily the thought that was in

everyone’s mind, that “Belgian neutrality might become a factor.” That was the

development Grey—and not he alone—was waiting for.

Britain’s predicament resulted from a split personality evident both within

the Cabinet and between the parties. The Cabinet was divided, in a split that

derived from the Boer War, between Liberal Imperialists represented by Asquith,

Grey, Haldane, and Churchill, and “Little Englanders” represented by all the rest.

Heirs of Gladstone, they, like their late leader, harbored a deep suspicion of

foreign entanglements and considered the aiding of oppressed peoples to be the

only proper concern of foreign affairs, which were otherwise regarded as a

tiresome interference with Reform, Free Trade, Home Rule, and the Lords’ Veto.

They tended to regard France as the decadent and frivolous grasshopper, and

would have liked to regard Germany as the industrious, respectable ant, had not

the posturings and roarings of the Kaiser and the Pan-German militarists

somehow discouraged this view. They would never have supported a war on

behalf of France, although the injection of Belgium, a “little” country with a just

call on British protection, might alter the issue.

Grey’s group in the Cabinet, on the other hand, shared with the Tories a

fundamental premise that Britain’s national interest was bound up with the

preservation of France. The reasoning was best expressed in the marvelously flat

words of Grey himself: “If Germany dominated the Continent it would be

disagreeable to us as well as to others, for we should be isolated.” In this epic

sentence is all of British policy, and from it followed the knowledge that, if the

challenge were flung, England would have to fight to prevent that “disagreeable”

outcome. But Grey could not say so without provoking a split in the Cabinet and

in the country that would be fatal to any war effort before it began.

Alone in Europe Britain had no conscription. In war she would be

dependent on voluntary enlistment. A secession from the government over the war

issue would mean the formation of an antiwar party led by the dissidents with

disastrous effect on recruiting. If it was the prime objective of France to enter war

with Britain as an ally, it was a prime necessity for Britain to enter war with a

united government.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

23

This was the touchstone of the problem. In Cabinet meetings the group

opposed to intervention proved strong. Their leader Lord Morley, Gladstone’s old

friend and biographer, believed he could count on “eight or nine likely to agree

with us” against the solution being openly worked for by Churchill with

“daemonic energy” and Grey with “strenuous simplicity.” From discussions in the

Cabinet it was clear to Morley that the neutrality of Belgium was “secondary to

the question of our neutrality in the struggle between Germany and France.” It was

equally clear to Grey that only violation of Belgium’s neutrality would convince

the peace party of the German menace and the need to go to war in the national

interest.

On August 1 the crack was visible and widening in Cabinet and

Parliament. That day twelve out of eighteen Cabinet members declared

themselves opposed to giving France the assurance of Britain’s support in war.

That afternoon in the lobby of the House of Commons a caucus of Liberal M.P.s

voted 19 to 4 (though with many abstentions) for a motion that England should

remain neutral “whatever happened in Belgium or elsewhere.” That week Punch

published “Lines designed to represent the views of an average British patriot”:

Why should I follow your fighting line

For a matter that’s no concern of mine? . . .

I shall be asked to a general scrap

All over the European map,

Dragged into somebody else’s war

For that’s what a double entente is for.

The average patriot had already used up his normal supply of excitement

and indignation in the current Irish crisis. The “Curragh Mutiny” was England’s

Mme. Caillaux. As a result of the Home Rule Bill, Ulster was threatening armed

rebellion against autonomy for Ireland and English troops stationed at the Curragh

had refused to take up arms against Ulster loyalists. General Gough, the Curragh

commander, had resigned with all his officers, whereupon Sir John French, Chief

of General Staff, resigned, whereupon Colonel John Seely, Haldane’s successor as

Secretary of War, resigned. The army seethed, uproar and schism ruled the

country, and a Palace Conference of party leaders with the King met in vain.

Lloyd George talked ominously of the “gravest issue raised in this country since

24

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

the days of the Stuarts,” the words “civil war” and “rebellion” were mentioned,

and a German arms firm hopefully ran a cargo of 40,000 rifles and a million

cartridges into Ulster. In the meantime there was no Secretary of War, the office

being left to Prime Minister Asquith, who had little time and less inclination for it.

Asquith had, however, a particularly active First Lord of the Admiralty.

When he smelled battle afar off, Winston Churchill resembled the war horse in

Job who turned not back from the sword but “paweth in the valley and saith

among the trumpets, Ha, ha.” He was the only British minister to have a perfectly

clear conviction of what Britain should do and to act upon it without hesitation.

On July 26, the day Austria rejected Serbia’s reply and ten days before his own

government made up its mind, Churchill issued a crucial order.

On July 26 the British fleet was completing, unconnected with the crisis, a

test mobilization and maneuvers with full crews at war strength. At seven o’clock

next morning the squadrons were due to disperse, some to various exercises on

the high seas, some to home ports where parts of their crews would be discharged

back into training schools, some to dock for repairs. That Sunday, July 26, the

First Lord remembered later was “a very beautiful day.” When he learned the

news from Austria he made up his mind to make sure “that the diplomatic

situation did not get ahead of the naval situation and that the Grand Fleet should

be in its War Station before Germany could know whether or not we should be in

the war and therefore if possible before we had decided ourselves.” The italics are

his own. After consultation with the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg,

he gave orders to the fleet not to disperse.

He then informed Grey what he had done and with Grey’s assent released

the Admiralty order to the newspapers in the hope that the news might have “a

sobering effect” on Berlin and Vienna.

Holding the fleet together was not enough; it must be got, as Churchill

expressed it in capitals, to its “War Station.” The primary duty of a fleet, as

Admiral Mahan, the Clausewitz of naval warfare, had decreed, was to remain “a

fleet in being.” In the event of war the British fleet, upon which an island nation

depended for its life, had to establish and maintain mastery of the ocean trade

routes; it had to protect the British Isles from invasion; it had to protect the

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

25

Channel and the French coasts in fulfillment of the pact with France; it had to

keep concentrated in sufficient strength to win any engagement if the German

fleet sought battle; and above all it had to guard itself against that new and

menacing weapon of unknown potential, the torpedo. The fear of a sudden,

undeclared torpedo attack haunted the Admiralty.

On July 28 Churchill gave orders for the fleet to sail to its war base at

Scapa Flow, far to the north at the tip of mist-shrouded Orkney in the North Sea.

It steamed out of Portland on the 29th, and by nightfall eighteen miles of warships

had passed northward through the Straits of Dover headed not so much for some

rendezvous with glory as for a rendezvous with discretion. “A surprise torpedo

attack” wrote the First Lord, “was at any rate one nightmare gone forever.”

Having prepared the fleet for action, Churchill turned his abounding

energy and sense of urgency upon preparing the country. He persuaded Asquith on

July 29 to authorize the Warning Telegram which was the arranged signal sent by

War Office and Admiralty to initiate the Precautionary Period. While short of the

Kriegesgefahr or the French State of Siege which established martial law, the

Precautionary Period has been described as a device “invented by a genius . . .

which permitted certain measures to be taken on the ipse dixit of the Secretary of

War without reference to the Cabinet . . . when time was the only thing that

mattered.”

Time pressed on the restless Churchill who, expecting the Liberal

government to break apart, went off to make overtures to his old party, the Tories.

Coalition was not in the least to the taste of the Prime Minister who was bent on

keeping his government united. Lord Morley at seventy-six was expected by no

one to stay with the government in the event of war. Not Morley but the far more

vigorous Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George, was the key figure whom

the government could not afford to lose, both for his proved ability in office and

his influence upon the electorate. Shrewd, ambitious, and possessed of a

spellbinding Welsh eloquence, Lloyd George leaned to the peace group but might

jump either way. He had suffered recent setbacks in public popularity; he saw a

new rival for party leadership arising in the individual whom Lord Morley called

“that splendid condottierre at the Admiralty”; and he might, some of his

colleagues thought, see political advantage in “playing the peacecard” against

Churchill. He was altogether an uncertain and dangerous quantity.

26

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

Asquith, who had no intention of leading a divided country into war,

continued to wait with exasperating patience for events which might convince the

peace group. The question of the hour, he recorded in his passionless way in his

diary for July 31, was, “Are we to go in or stand aside. Of course everybody longs

to stand aside.” In a less passive attitude, Grey, during the Cabinet of July 31

almost reached the point-blank. He said Germany’s policy was that of a

“European aggressor as bad as Napoleon” (a name that for England had only one

meaning) and told the Cabinet that the time had come when a decision whether to

support the Entente or preserve neutrality could no longer be deferred. He said

that if it chose neutrality he was not the man to carry out such a policy. His

implied threat to resign echoed as if it had been spoken.

“The Cabinet seemed to heave a sort of sigh,” wrote one of them, and sat

for several moments in “breathless silence.” Its members looked at one another,

suddenly realizing that their continued existence as a government was now in

doubt. They adjourned without reaching a decision.

That Friday, eve of the August Bank Holiday weekend, the Stock

Exchange closed down at 10:00 A.M. in a wave of financial panic that had started

in New York when Austria declared war on Serbia and which was closing

Exchanges all over Europe. The City trembled, prophesying doom and the

collapse of foreign exchange. Bankers and businessmen, according to Lloyd

George, were “aghast” at the idea of war which would “break down the whole

system of credit with London at its center.” The Governor of the Bank of England

called on Saturday to inform Lloyd George that the City was “totally opposed to

our intervening” in a war.

That same Friday the Tory leaders were being rounded up and called back

to London from country houses to confer on the crisis. Dashing from one to the

other, pleading, exhorting, expounding Britain’s shame if the shilly-shallying

Liberals held back now, was Henry Wilson, the heart, soul, spirit, backbone, and

legs of the Anglo-French military “conversations.” The agreed euphemism for the

joint plans of the General Staffs was “conversations.” The formula of “no

commitment” which Haldane had first established, which had raised misgivings in

Campbell-Bannerman, which Lord Esher had rejected, and which Grey had

embodied in the 1912 letter to Cambon still represented the official position, even

if it did not make sense.

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

27

It made very little. If, as Clausewitz justly said, war is a continuation of

national policy, so also are war plans. The Anglo-French war plans, worked out in

detail over a period of nine years, were not a game, or an exercise in fantasy or a

paper practice to keep military minds out of other mischief. They were a

continuation of policy or they were nothing. They were no different from France’s

arrangements with Russia or Germany’s with Austria except for the final legal

fiction that they did not “commit” Britain to action. Members of the government

and Parliament who disliked the policy simply shut their eyes and mesmerized

themselves into believing the fiction.

M. Cambon, visiting Opposition leaders after his painful interview with

Grey, now dropped diplomatic tact altogether. “All our plans are arranged in

common. Our General Staffs have consulted. You have seen all our schemes and

preparations. Look at our fleet! Our whole fleet is in the Mediterranean in

consequence of our arrangements with you and our coasts are open to the enemy.

You have laid us wide open!” He told them that if England did not come in France

would never forgive her, and ended with a bitter cry, “Et l’honneur? Est-ce-que

l’Angleterre comprend ce que c’est l’honneur?”

Honor wears different coats to different eyes, and Grey knew it would

have to wear a Belgian coat before the peace group could be persuaded to see it.

That same afternoon he dispatched two telegrams asking the French and German

governments for a formal assurance that they were prepared to respect Belgian

neutrality “so long as no other power violates it.” Within an hour of receiving the

telegram in the late evening of July 31, France replied in the affirmative. No reply

was received from Germany.

Next day, August 1, the matter was put before the Cabinet. Lloyd George

traced with his finger on a map what he thought would be the German route

through Belgium, just across the near corner, on the shortest straight line to Paris;

it would only, he said, be a “little violation.” When Churchill asked for authority

to mobilize the fleet, that is, call up all the naval reserves, the Cabinet, after a

“sharp discussion,” refused. When Grey asked for authority to implement the

promises made to the French Navy, Lord Morley, John Burns, Sir John Simon,

and Lewis Harcourt proposed to resign. Outside the Cabinet, rumors were swirling

of the last-minute wrestlings of Kaiser and Czar and of the German ultimatums.

Grey left the room to speak to—and be misunderstood by—Lichnowsky on the

telephone, and unwittingly to be the cause of havoc in the heart of General

Moltke. He also saw Cambon, and told him “France must take her own decision at

28

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

this moment without reckoning on an assistance we are not now in a position to

give.” He returned to the Cabinet while Cambon, white and shaking, sank into a

chair in the room of his old friend Sir Arthur Nicolson, the Permanent UnderSecretary. “Ils vont nous lacher” (They are going to desert us), he said. To the

editor of The Times who asked him what he was going to do, he replied, “I am

going to wait to learn if the word ‘honor’ should be erased from the English

dictionary.”

In the Cabinet no one wanted to burn his bridges. Resignations were

bruited, not yet offered. Asquith continued to sit tight, say little, and await

developments as that day of crossed wires and complicated frenzy drew to a close.

That evening Moltke was refusing to go east, Lieutenant Feldmann’s’s company

was seizing Trois Vierges in Luxembourg, Messimy over the telephone was

reconfirming the ten-kilometer withdrawal, and at the Admiralty the First Lord

was entertaining friends from the Opposition, among them the future Lords

Beaverbrook and Birkenhead. To keep occupied while waiting out the tension,

they played bridge after dinner. During the game a messenger brought in a red

dispatch box—it happened to be one of the largest size. Taking a key from his

pocket, Churchill opened it, took out the single sheet of paper it contained, and

read the single line on the paper: “Germany has declared war on Russia.” He

informed the company, changed out of his dinner jacket, and “went straight out

like a man going to a well-accustomed job.”

Churchill walked across the Horse Guards Parade to Downing Street,

entered by the garden gate, and found the Prime Minister upstairs with Grey,

Haldane, now Lord Chancellor, and Lord Crewe, Secretary for India. He told them

he intended “instantly to mobilize the fleet notwithstanding the Cabinet decision.”

Asquith said nothing but appeared, Churchill thought, “quite content.” Grey,

accompanying Churchill on his way out, said to him, “I have just done a very

important thing. I have told Cambon that we shall not allow the German fleet to

come into the Channel.” Or that is what Churchill, experiencing the perils of

verbal intercourse with Grey, understood him to say. It meant that the fleet was

now committed. Whether Grey said he had given the promise or whether he said,

as scholars have since decided, that he was going to give it the next day, is not

really relevant, for whichever it was it merely confirmed Churchill in a decision

already taken. He returned to the Admiralty and “gave forthwith the order to

mobilize.”

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

29

Both his order and Grey’s promise to make good the naval agreement with

France were contrary to majority Cabinet sentiment. On the next day the Cabinet

would have to ratify these acts or break apart, and by that time Grey expected a

“development” to come out of Belgium. Like the French, he felt that he could

count on Germany to provide it.

30

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

QUESTION

In the description above, what role does international law play in

international politics? (I suggest that you make a list of all the places in the text at

which international law is mentioned; for each place where international law is

mentioned, you should briefly describe, inter alia, whether those involved treated

international legal obligations seriously.)

CHAPTER EIGHT—ULTIMATUM IN BRUSSELS

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

31

Locked in the safe of Herr Von below Saleske, German Minister in

Brussels, was a sealed envelope brought to him by special courier from Berlin on

July 29 with orders “not to open until you are instructed by telegraph from here.”

On Sunday, August 2, Below was advised by telegram to open the envelope at

once and deliver the Note it contained by eight o’clock that evening, taking care to

give the Belgian government “the impression that all the instructions relating to

this affair reached you for the first time today.” He was to demand a reply from

the Belgians within twelve hours and wire it to Berlin “as quickly as possible” and

also “forward it immediately by automobile to General von Emmich at the Union

Hotel in Aachen.” Aachen or Aix-la-Chapelle was the nearest German city to

Liège, the eastern gateway to Belgium.

Herr von Below, a tall, erect bachelor with pointed black mustaches and a

jade cigarette holder in constant use, had taken up his post in Belgium early in

1914. When visitors to the German Legation asked him about a silver ash tray

pierced by a bullet hole that lay on his desk, he would laugh and reply: “I am a

bird of ill omen. When I was stationed in Turkey they had a revolution. When I

was in China, it was the Boxers. One of their shots through the window made that

bullet hole.” He would raise his cigarette delicately to his lips with a wide and

elegant gesture and add: “But now I am resting. Nothing ever happens in

Brussels.”

Since the sealed envelope arrived, he had been resting no longer. At noon

on August 1 he received a visit from Baron de Bassompierre, Under-Secretary of

the Belgian Foreign Office, who told him the evening papers intended to publish

France’s reply to Grey in which she promised to respect Belgian neutrality.

Bassompierre suggested that in the absence of a comparable German reply, Herr

von Below might wish to make a statement. Below was without authority from

Berlin to do so. Taking refuge in diplomatic maneuver, he lay back in his chair

and with his eyes fixed on the ceiling repeated back word for word through a haze

of cigarette smoke everything that Bassompierre had just said to him as if playing

back a record. Rising, he assured his visitor that “Belgium had nothing to fear

from Germany,” and closed the interview.

Next morning he repeated the assurance to M. Davignon, the Foreign

Minister, who had been awakened at 6:00 A.M. by news of the German invasion

of Luxembourg and had asked for an explanation. Back at the legation, Below

32

TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

soothed a clamoring press with a felicitous phrase that was widely quoted, “Your

neighbor’s roof may catch fire but your own house will be safe.”

Many Belgians, official and otherwise, were disposed to believe him, some

from pro-German sympathies, some from wishful thinking, and some from simple

confidence in the good faith of the international guarantors of Belgium’s

neutrality. In seventy-five years of guaranteed independence they had known

peace for the longest unbroken period in their history. The territory of Belgium

had been the pathway of warriors since Caesar fought the Belgae. In Belgium,

Charles the Bold of Burgundy and Louis XI of France had fought out their long

and bitter rivalry; there Spain had ravaged the Low Countries; there Marlborough

had fought the French at the “very murderous battle” of Malplaquet; there

Napoleon had met Wellington at Waterloo; there the people had risen against

every ruler—Burgundian, French, Spanish, Hapsburg, or Dutch—until the final

revolt against the House of Orange in 1830. Then, under Leopold of Saxe-Coburg,

maternal uncle of Queen Victoria, as King, they had made themselves a nation,

grown prosperous, spent their energies in fraternal fighting between Flemings and

Walloons, Catholics and Protestants, and in disputes over Socialism and French

and Flemish bilingualism, in the fervent hope that their neighbors would leave

them to continue undisturbed in this happy condition.

The King and Prime Minister and Chief of Staff could no longer share the

general confidence, but were prevented, both by the duties of neutrality and by

their belief in neutrality, from making plans to repel attack. Up until the last

moment they could not bring themselves to believe an invasion by one of their

guarantors would actually happen. On reaming of the German Kriegesgefahr on

July 31, they had ordered mobilization of the Belgian Army to begin at midnight.

During the night and next day policemen went from house to house ringing

doorbells and handing out orders while men scrambled out of bed or left their

jobs, wrapped up their bundles, said their farewells, and went off to their

regimental depots. Because Belgium, maintaining her strict neutrality, had not up

to now settled on any plan of campaign, mobilization was not directed against a

particular enemy or oriented in a particular direction. It was a call-up without

deployment. Belgium was obligated, as well as her guarantors, to preserve her

own neutrality and could make no overt act until one was made against her.

When, by the evening of August 1, Germany’s silence in response to

Grey’s request had continued for twenty-four hours, King Albert determined on a

BARBARA TUCHMAN, THE GUNS OF AUGUST

33

final private appeal to the Kaiser. He composed it in consultation with his wife,

Queen Elizabeth, a German by birth, the daughter of a Bavarian duke, who

translated it sentence by sentence into German, weighing with the King the choice

of words and their shades of meaning. It recognized that “political objections”

might stand in the way of a public statement but hoped “the bonds of kinship and

friendship” would decide the Kaiser to give King Albert his personal and private

assurance of respect for Belgian neutrality. The kinship in question, which

stemmed from King Albert’s mother, Princess Marie of HohenzollernSigmaringen, a distant and Catholic branch of the Prussian royal family, failed to

move the Kaiser to reply.

Instead came the ultimatum that had been waiting in Herr von Below’s

safe for the last four days. It was delivered at seven on the evening of August 2

when a footman at the Foreign Office pushed his head through the door of the

Under-Secretary’s room and reported in an excited whisper, “The German

Minister has just gone in to see M. Davignon!” Fifteen minutes later Below was

seen driving back down the Rue de la Loi holding his hat in his hand, beads of

perspiration on his forehead, and smoking with the rapid, jerky movements of a

mechanical toy. The instant his “haughty silhouette” had been seen to leave the

Foreign Office, the two Under-Secretaries rushed in to the Minister’s room where

they found M. Davignon, a man until now of immutable and tranquil optimism,

looking extremely pale. “Bad news, bad news,” he said, handing them the German

note he had just received. Baron de Gaiffier, the Political Secretary, read it aloud,

translating slowly as he went, while Bassompierre, sitting at the Minister’s desk

took it down, discussing each ambiguous phrase to make sure of the right

rendering. While they worked, M. Davignon and his Permanent Under-Secretary,

Baron van der Elst, listened, sitting in two chairs on either side of the fireplace.

M. Davignon’s last word on any problem had always been, “I am sure it will turn

out all right” while van der Elst’s esteem for the Germans had led him in the past

to assure his government that rising German armaments were intended only for

the Drang nach Osten and portended no trouble for Belgium.

Baron de Broqueville, Premier and concurrently War Minister, entered the

room as the work concluded, a tall, dark gentleman of elegant grooming whose