The Nature of Art Appreciation and Criticism

advertisement

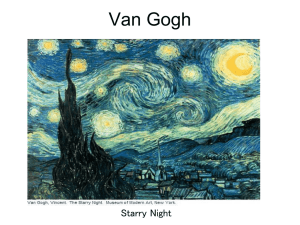

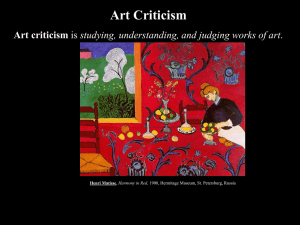

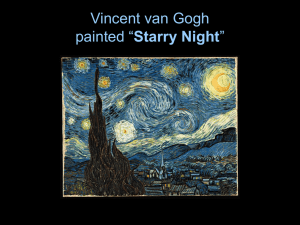

Art Criticism 1 The Nature of Art Appreciation and Criticism From Chapter 12, Art Criticism, Hurwitz, A. and M. Day. (2001). Children and Their Art, Seventh Edition. NY: Harcourt College Publishers Art Appreciation, although an outmoded term associated with picture-study movement of the early 1920s, still has some validity. The word appreciation means “valuing” or having a sense of an object’s worth through the familiarity one gains by sustained, guided study. Appreciation also involves the acquisition of knowledge related to the object, the artist, the materials used, the historical and stylistic setting, and the development of a critical sense. If we accept the fact that critics as well as artists can be models for artistic study, we must think about how critics operate. There are journalistic critics who write for the general public and who avoid the more profound level of writing, and there are critics who work for art journals who are knowledgeable in history and aesthetics and use language in such a way that criticism itself becomes an art form. The goal of all critics is the same: to provide the readers with information regarding an artist or an exhibit and, beyond that, to help the readers to increase their understanding by viewing art through the informed eye that good critics are assumed to posses. A good way to understand the phases of criticism is to read an art review to see how the reviewer goes about discussing either an exhibition or a single work. If we study excerpts from the following review, we can gain a clearer idea of the kinds of content that occupy critics. The painting under discussion is Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night. Key passages have been selected from the review to distinguish four phases of discussion: descriptive, analytical, interpretative, and historical. The judgment about the work’s quality is implicit in the critic’s choice of this painting. We begin with a statement by the artist, van Gogh, which provides historical context. Historical: “I devour nature ceaselessly. I exaggerate, sometimes I make changes in the subject, but still I don’t invent the whole picture, on the contrary I find it already there; it is a question of picking out what one wants from nature.” In a discussion of the painting, we find illustration of the other three modes of critical approach to the artwork. Descriptive: “I look at van Gogh’s painting, The Starry Night. You can easily recognize village, trees, moon, stars; but clearly this is not the point.” Analytical: “We can point to certain qualities of the brushwork and relate them to the impact of the total work. The individual strokes are ‘rough,’ they vary, although they hold to a definite scale or size…. These patterns are in themselves dynamic and they are insistently repeated.” Art Criticism 2 Interpretative: “….you are at once impressed by a grand, almost hypnotic rhythm which binds all the representational elements together into a kind of cosmic unity…van Gogh lays bare his very act of painting and it is partly through the suggestion of his physical activity that we share his emotions.” When we utilize a knowledge base in art, we deal with information surrounding a work (names, dates, places), as well as facts concerning physical details taken from the work itself (subject matter, media, colors). Knowledge also includes those concepts of design, technique, and style that the teacher feels can enable the student to “read” a painting. Appreciation can begin in a spontaneous, intuitive reaction, but it does not end there. One way to arrive at a deeper level of response is to understand the difference between looking and seeing, and, in order to do this; we can employ a process used by professional art critics, as illustrated in the review cited here. The goal of the critical phase of the larger appreciation process is to be able to respond more fully to an artwork and to defend one’s opinion regarding it. In the historical phase of criticism a good deal of emphasis is placed on the context of the work: when, where, and how the work was created, its function within the culture or origin, relationships with other prominent works or movements in art, and values of the society from which the work emerged. Some critics include economic, religious, technical and other perspectives. The descriptive phase focuses on aspects most of us generally perceive commonly. The description may be objective items in which few will disagree or may be personalized or evocative which may be controversial. The description is generally adjectives that tell what is observed. The analytical phase also has a perceptional basis but takes the descriptive phase a step further by requiring the viewer to discuss the structure or composition of the artwork. The viewer describes how the artist uses the elements and principles of design in his artwork. In the interpretative phase, the critic moves to more imaginative levels and is invited to speculate about the meaning embodied in a work or the purpose the artist may have had in mind. The critical process normally ends with a judgment – that is, a conclusion regarding the success or failure of an artwork and its ranking with other artworks. It is useful to recognize the distinction between preference and judgment in response to works of art. Preferences are not subject to correction by authority or persuasion since one’s personal liking or disliking of an artwork is an aspect of one’s individuality. Judgment, however, is subject to argumentation and persuasion.