Analysis of the Economic, Employment and Social Profile

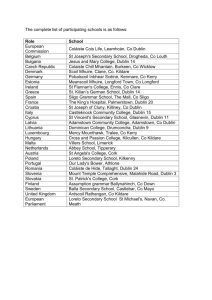

advertisement