ENVE3503: Mass Balance, Kinetics & Reactors Expectations

advertisement

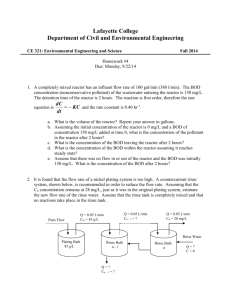

ENVE3503 Expectations Chapter 4. Mass Balance, Kinetics and Reactors, and Mass Transport 1. Mass Balance a. Basics: be able to write the mass balance on a control volume: dm min mout m reaction dt and express that mass balance in terms of concentration: V F IJ G HK dC dC Q Cin Q C V dt dt rxn only b. Kinetics: know the difference between conservative and reactive substances, applying the Kinetic Rate Law: dC k Cn dt to differentiate between zero and first order reactions and provide the reaction rate coefficient for each. Be able to use the analytical solutions for zero- and first-order rate equations: Ct C0 e k t Ct C0 k t to calculate concentration as a function of time. Be able to apply the first order kinetics in determining a chemical’s half-life. Be able to adjust both zero- and first-order rate coefficients for changes in temperature: kT k20 T 20 c. Reactor Analogs: know the three types of reactor analogs (batch, plug flow and completely-mixed flow) and be able to provide examples of their application to both natural and engineered systems. 1 d. Plug Flow Reactors: understand how the equation for a batch reactor becomes the solution for a plug flow reactor, i.e. by considering a train of batch reactors with position now equated with time, C t C0 e k t ; batch reactor or plug flow with ‘t’ = time of travel; C L C0 e k L ; plug flow with time given by retention time, L Thus, given an initial concentration, one might ask: (1) how long would the water need to be in the reactor, (2) would the retention time of the reactor be or (3) given velocity, what would the length of the reactor be to yield a particular percent reduction. e. Completely-Mixed Flow Reactors: understand the implications of the ‘completelymixed’ and ‘constant volume’ assumptions used in deriving the CMFR mass balance. Be able to apply the general mass balance expression: V F IJ G HK dC dC Q Cin Q C V dt dt rxn only to the behavior of a conservative substance at steady state in a CMFR, i.e. the mixing basin calculation: V dC Qup Cup Qin Cin Q C dt and Cmb Qup Cup Qin Cin Q C Be able to apply the general mass balance expression: V F IJ G HK dC dC Q Cin Q C V dt dt rxn only to a CMFR, solving that equation at steady state for a reactive substance (e.g. first order decay), Css Cin Q Q V k to obtain the steady state concentration. 2 Understand the concept of retention time: V Q and be able to calculate for any type of reactor. Know when a steady state solution is appropriate and when a time variable approach should be used, by determining the 95% response time for the reactor: t95% ln 0.05 3 1 1 k k Be able to apply (not derive; not memorize) the time variable solution to the mass balance equation: 1 1 k t k t Ct Css1 e Css2 1 e to calculate concentration as a function of time as a system moves between two steady states. f. Reactor Comparison: understand the characteristics of PFRs and CMFRs and be able to explain why PFRs are inherently more efficient. Also understand why CMFRs might be a better solution for some situations, even though they are inherently less efficient. 2. Mass Transport a. Basics Understand the role of mass transport in governing pollutant fate in natural and engineered systems. Be able to define and differentiate the two basic types of mass transport, advection and diffusion, and describe the difference between molecular and turbulent diffusion. b. Advection: be able to recognize the advection terms in the generalized mass balance, V F I G HJ K dC dC Q Cin Q C V dt dt 3 rxn only c. Diffusion: be able to express diffusion as a mass flux density: mdiff J diff A realizing that mass flux density due to diffusion is related to the diffusion coefficient and the concentration gradient as defined by Fick’s First Law: J diff D dC dx The mass balance for a completely-mixed volume in a lake is given by: V dC J diff A dt and substituting the definition of diffusion: V dC dC D A dt dx Be able to apply this equation to compute a mass flux. Mass Balance, Reactor and Mass Transport Problems Batch Reactor: initial chemical concentration = 100 mg∙L-1; zero order rate coefficient = 0.1 mg∙L-1∙d-1; first order rate coefficient = 0.1 d-1; = 1.08. 1. Calculate the time required to reduce the concentration of the chemical by 90% if decay follows zero-order kinetics. [900 days] 2. Calculate the time required to reduce the concentration of the chemical by 90% if decay follows first order kinetics. [23 days] 3. Calculate half-life of the chemical at 20 °C. [6.9 days] 4. Calculate half-life of the chemical at 35 °C. [2.2 days] 4 Plug Flow Reactor: initial chemical concentration = 100 mg∙L-1; first order rate coefficient = 3 d-1; inflow = 100 m3∙d-1; reactor configuration, column, length = 10 m, cross-sectional area = 1 m2. 5. Determine the effluent chemical concentration. [74 mg/L] 6. Determine the required column length to achieve a 95% reduction in chemical concentration. [100 m] Completely-Mixed Flow Reactor: initial chemical concentration = 100 mg∙L-1; first order rate coefficient = 3 d-1; inflow = 100 m3∙d-1; reactor volume = 10 m3. 7. Calculate the steady-state effluent concentration. [40 mg∙L-1] 8. Calculate the reactor retention time. [0.1 days] 9. Calculate the 95% response time for the reactor and for the reactor with a conservative substance. [0.3 days] 10. Calculate the reactor concentration 0.25 days following a 50% reduction in the influent chemical concentration. [51.9 mg∙L-1] 11. Compare the effluent chemical concentrations for PFR and CMFR. Which is more efficient? Why? Are there any applications for which the reactor that performs less efficiently would be a better choice? [see material beginning at the bottom of p. 122] Diffusion: the transport of organic chemicals from air to water is governed by diffusion across a stagnant film of air located immediately above the air-water interface. Polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a class of chemicals generated through coke production, coal combustion and other activities. Total PAH levels in the bulk air at a site in Chicago near Lake Michigan were 300 ng·m-3 and at the water surface were 50 ng·m-3. Assume a stagnant film thickness of 2 cm and a diffusion coefficient in air for PAHs of 5x10-6 m2·s-1. 12. Calculate the mass flux density (J, g·m-2·yr-1) and mass flux (MT·yr-1) of PAHs to Lake Michigan by diffusion. [1.97x10-3; 114 MT·yr-1] 5