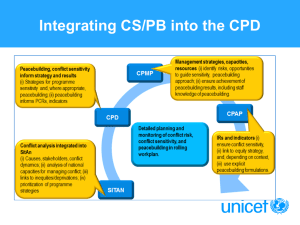

Analysis of information and monitoring systems

advertisement