Coversheet for submissions - Emissions reduction

advertisement

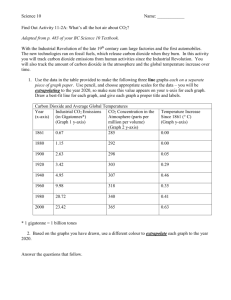

Renewable Energy Target Review: David Arthur Submission This submission makes two arguments: 1) From the perspective of avoiding adverse climate change, a 5% decrease in CO2 emissions by 2020 is too little, too late. From a perspective of seeking to sustainably maintain Australian living conditions, the only acceptable goal has to be total cessation of fossil fuel use as rapidly as is economically and technologically feasible. It is therefore not possible to accept that the present Renewable Energy Target be decreased. 2) Irrespective of whether there is an Emissions Reduction Fund or not, a “carbon price” imposed through a revenue-neutral consumption tax on fossil fuel provides the necessary price signal to guide and inform emission-reducing activities with minimal regulatory intervention, minimal administrative effort, yet achieve maximum emission reduction with optimal economic efficiency. The submission concludes with reference to a paper from the peer-reviewed literature, that encapsulates many of the arguments put forward here. 1. A 5% decrease in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2020 is insufficient: total cessation of fossil fuel use as rapidly as is economically and technologically feasible is required. Over the 5 million years before industrial civilisation developed (that is, since the start of the Pliocene Epoch), earth’s climate gradually cooled from a relatively warm state, with sea levels perhaps 25 m higher than present, largely due to ice-free Greenland and much less ice on the Antarctic Peninsula, to the excessive frigidity of the Pleistocene “Ice Ages”, with sea levels perhaps 120 m lower than present and ice-sheets across northern Eurasia and North America, interspersed with relatively benign conditions similar to the Holocene Epoch of the last 10 or 11 millennia within which all recorded human history has occurred. Each of these climate conditions has been associated with and is due to the atmospheric concentration of CO2 which prevailed at the time: ~400 ppm in the case of the early Pliocene, ~200 ppm during Pleistocene Ice Ages, and ~300 ppm during Pleistocene interglacial, ‘warm’ periods and also during the most recent Holocene Epoch, which saw the advent of human civilisation. This climate history is indicated by the history of global average temperature shown in Figure 1, below. 2 ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Five_Myr_Climate_Change.png) Figure 1: A global average temperature record from multiple overlapping sediment cores for the Pliocene, Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs (ie last ~five million years of earth history Ref: Lisiecki, L. E., and M. E. Raymo (2005), A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic d18O records, Paleoceanography, 20, PA1003, doi:10.1029/2004PA001071., as rendered in Wikipedia. Note that reference temperature (0 degrees) for Equivalent Vostok T is ~16th century global average temperature. To avoid dangerous climate change, we needed to have totally ceased using coal, oil and gas by 1988, because that's when industrial CO2 emissions caused atmospheric CO2 to exceed 350 ppm for the first time in >3 million years. In fact, with atmospheric CO2 close to 400 ppm, atmospheric composition is closer to that of the early Pliocene Epoch, ~4-5 million years ago. At that time1, the Arctic Ocean was ice-free during the summer months, Greenland was all but ice-free, and there was substantially less ice cover on the Antarctic Peninsula and West Antarctica. Pliocene sea levels are understood to have been 10-20 m higher than present. To forestall the world’s climate and sea levels reverting to a Pliocene-like state, it is necessary to return atmospheric CO2 to less than 350 ppm2 as rapidly as can be achieved. The first step towards achieving this goal is to cease using all coal, oil and gas as quickly as we can, and I applaud the Federal Government in taking at least an initial step toward that goal. However, as the above argument suggests, and as the supporting documentation from the peer-reviewed scientific literature demonstrates, the goal of the present Direct Action plan is insufficient. 2. A “carbon price” is best imposed through a revenue-neutral consumption tax on fossil fuel Such a price would provide the necessary price signal to guide and inform emission-reducing activities with 1 Attachments explaining this include “Significantly warmer Arctic surface temperatures during the Pliocene indicated by multiple independent proxies”, Ballantyne et al, Geology 2010;38;603-606 doi: 10.1130/G30815.1 (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 1), and Fedorov et al, “Patterns and mechanisms of early Pliocene warmth”, doi:10.1038/nature12003 (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 2). 2 Hansen et al (2008), “Target Atmospheric CO2: Where Should Humanity Aim?” (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 3). minimal regulatory intervention, minimal administrative effort, yet achieve maximum emission reduction with optimal economic efficiency3 A major issue in pricing CO2 emissions is that putting a direct charge on production of CO2 emissions is that this cannot be done on imported goods. If any jurisdiction imposes a charge on activity that produces CO2 emissions, it has effectively imposed an incentive for productive activities (such as manufacturing) to relocate to another jurisdiction where there is no charge on CO2 emissions, and satisfy market demand for its products in the CO2 emission-pricing jurisdiction by imports. This is doubly ineffective, because not only have overall CO2 emissions not been decreased, they have increased due to the added CO2 emissions of shipping goods from nation of production to nation of consumption. EU carbon pricing, for example, has seen much manufacturing activity outsourced to China, to the detriment of European manufacturing and with increased CO2 emissions due to additional shipping. Mr Rudd’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme had exactly this flaw, and hence would have driven precisely this de-industrialisation in Australia had it not, prudently, been rejected in the Senate. Geoff Carmody’s essay “Consumptionbased emissions policy: A vaccine for the CPRS ‘trade-flu’?”4 sets out this argument in more detail. Michael Porter’s contribution “Reforms in the greenhouse era: Who pays, and 3 Demonstrated by Martin Weitzman in the seminal 1974 paper on economic pollution control, “Prices vs. Quantities” (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 4); The relative merits of acting to minimise damaging pollution by either price-setting (effectively, consumption taxation) or emissioncapping (effectively, a ‘market mechanism’ as apparently preferred by the ALP) were compared by Weitzman, concluding that price-setting to guide and inform individual pollution-limiting action is optimally efficient. contained in CEDA’s June 2011 publication “A Taxing Debate: The forgotten issues of climate policy” (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 5). 4 2 how?” to the same CEDA publication makes the case that driving CO2 emissions reduction by trading in derivatives of CO2 emissions is not conducive to economic stability, as demonstrated by the role of derivative trading in creating the conditions for the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). For further discussion of why the existing Kyoto / EU emphasis on CO 2 emission production is flawed, Glen Peters's 'The Conversation' piece, "Carbon as a commodity: a trade in pollution could help clean up dirty economies"5 helps explain why an emphasis on fossil fuel consumption is of greater value than schemes based on CO2 emissions production. Indeed, it was the trade implications of the carbon-pricing mechanism proposed under the Kyoto Protocol that lead the Howard government to rightly conclude that joining the Kyoto Protocol was not in Australia’s best interests, and it is the same trade implications that have kept the USA from agreeing to the Protocol under both Bush and Obama presidencies. There's an easier way to provide a steady price on CO2 emissions that will guide and inform emission-reducing choices by businesses and individuals, and that's to make pro rata cuts to existing taxes to make way for a consumption tax on fossil fuel6. Transferring the "burden of taxation" onto fossil fuel consumption in this way provides an incentive for taxpayers to find alternative energy sources for their activities, and also provides them with a price guide on what their optimal (least overall tax) fossil fuel use might be from year to year. To get further reductions in fossil fuel consumption in subsequent years, simply raise the rate of the tax, with corresponding adjustments to all other tax rates, until fossil fuel consumption has decreased to the extent required. 5 6 (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 6) Explained by Oxford Energy Policy Professor Dieter Helm in his book "The Carbon Crunch", also in his 8 Nov 2012 online opinion piece “Forget Kyoto: Putting a Tax on Carbon Consumption” (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 7). 3 To ensure a ‘level playing field’, consumption taxes are imposed on imports to a tax jurisdiction through WTO-compliant 7 “border adjustment” charges. This has the benefit of maintaining competitiveness of domestic industries against imported rivals through a WTO-compliant mechanism. Concluding Remarks This submission 1. summarises and refers to peer-reviewed evidence that the goal climate policy must be the complete cessation of all coal, oil and natural gas use as soon as economically feasible, and 2. because this cessation can and will be achieved by technological transformation, this submission then summarises and refers to some expert writing that describes the economically optimal pricing mechanism to guide and inform this technological transformation. As it happens, a paper in the peer-reviewed literature makes similar arguments; Hansen J, Kharecha P, Sato M, Masson-Delmotte V, Ackerman F, et al. (2013) Assessing ‘‘Dangerous Climate Change’’: Required Reduction of Carbon Emissions to Protect Young People, Future Generations and Nature. PLoS ONE 8(12): e81648. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081648 8, also accompanying this submission as Attachment 10. 7 Veel, “Carbon Tariffs And The WTO: An Evaluation Of Feasible Policies” Journal of International Economic Law 12(3), 749–800 doi:10.1093/jiel/jgp031 (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 8), Pauwelyn (2012), “Carbon Leakage Measures and Border Tax Adjustments Under WTO Law”, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (IHEID), Switzerland (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 9) 8 (pdf accompanying to this submission as Attachment 10) 4