Ozone Attack

advertisement

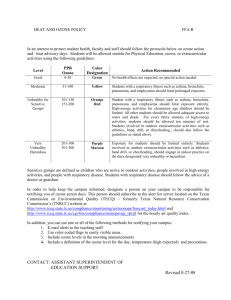

Ozone Attack In this activity, students will observe how ozone can damage rubber bands and through a comparison, they will be able to determine the relative ozone levels for different locations. Background Ozone is present in the air that surrounds us. It is formed when hydrocarbons (HCs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) from forests, industries, and automobile exhaust react with heat and sunlight. This tropospheric ozone is often called "bad" ozone because it damages living tissue. Some tropospheric ozone is natural. Lightning and static discharges are one natural source of tropospheric ozone. Ozone gives off the acrid smell after a lightning discharge. Some ozone is also produced when natural hydrocarbons formed by trees and other vegetation react with nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere and sunlight. This activity is based on the high oxidation capacity of ozone, which causes rubber and plastic products to break down after relatively short exposure. By observing how rubber bands deteriorate and develop cracks or pits, the relative ozone levels can be determined for different locations. If you would like to extend this activity into an inquiry-based laboratory for your students, a guide has been included along with a sample lab report format. Note: The xerographic process in most copy machines uses electrostatic charging of a cylinder. The accompanying ionization creates ozone in adjacent air, so a room containing a copy machine makes a good location for this experiment. Learning Goals 1. Students will understand that tropospheric ozone is often called "bad" ozone because it breaks down certain materials. 2. Students will be able to explain that concentrations of ozone are not uniform. 3. Students will be able to demonstrate that the longer the exposure to ozone, the greater the effect. Alignment to National Standards National Science Education Standards Science As Inquiry, Grades 5 to 8, pp. 143: "Content Standard A: As a result of activities in grades 5 - 8, all students should develop abilities to do scientific inquiry and understandings about scientific inquiry." Benchmarks for Science Literacy, Project 2061, AAAS Scientific Inquiry, all grades, pgs. 9-13. Grade level: 6 to 9 Time: Variable depending on the nature of the student experiment but use the following as a general guide: Introduction by teacher: 20 minutes Experiment set-up by students: 20 minutes Daily observations for at least one week: 5 minutes Discussion and comparison of results: 30 minutes Materials (per group of students) 3 glass jars or beakers 3 medium size rubber bands Hand lens Felt pen Procedure 1. Have students work in groups of 2 or 3. Each group will have 3 jars or beakers and 3 medium size rubber bands, and will place each jar in a different location. 2. Place a rubber band around each glass jar or beaker near the center without stretching it very much. (The results of this experiment will be altered if the rubber bands are stretched a great deal.) 3. Write the group name, starting date, and location on a piece of paper and place it on the beaker or jar. 4. Use the hand lens to observe a section of the rubber band. Mark this section with a felt pen. 5. Make a drawing of this section showing the condition of the rubber band. 6. Place one jar outside away from direct sunlight. Place one jar in the classroom. Place one jar near the copy machine. 7. Observe and record (write and draw) changes within the marked section each day for the next week. Observations and Questions 1. Make drawings and a table describing the observable changes in the rubber bands. (Cracking or pitting of the rubber bands should be observed in some locations.) 2. Which location showed the greatest changes? Which location showed the least changes? (Answers will vary. Usually the sample near the copy machine will show more changes.) 3. On which day did you first see noticeable changes? (Answers will vary depending upon the ozone concentration.) 4. Did all the rubber bands change on the same day? (Probably not.) 5. What do you think may have caused the change in the rubber bands? (Ozone will deteriorate the rubber bands at a rate dependent upon the ozone levels in the surrounding air.) 6. What might explain why you observed different degrees of change in various locations? (Hopefully students will relate the amount of change to different ozone levels.) 7. What do you think the effect on the rubber bands might suggest about any possible effect of ozone on living tissue, such as plants or your own lungs? (Scientists are studying if there is a direct relationship between ozone levels and the amount of damage to biological materials.) 8. Describe in a short paragraph why your data might suggest possible hazards to people who work in copy rooms. (Scientists are trying to determine if high concentrations of ozone might be harmful to tissues of people working for long periods of time near copy machines.) Extensions 1. Have students try different sizes of rubber bands, stretching versus not stretching the rubber bands, nylon stockings, different types of plastics, etc., at different locations, for different amounts of time. Students can look at differences in ozone levels at different street intersections, since ozone is formed by the interaction of hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides with sunlight. Students should keep a record of weather conditions, particularly sunlight, and level of air pollution during the recording time. The health department in some cities records pollution levels, including ozone levels. 2. Determine the economic impact of changes in tropospheric ozone. Things to consider: cost of ozone damage to materials such as tires, rubber, and plastics; costs and benefits of pollution mitigation. 3. Consider the impact ozone has upon society, for example, health care, crop damage, etc. Assessment Ideas This would serve well as a scientific inquiry task and allow the teacher to assess student understanding of ozone effects as well as the students' ability to design and conduct simple, independent experiments. A simple laboratory report would be an appropriate assessment tool. Modifications for Alternative Learners English Language Limited (ELL) students should be able to carry out this lab with little difficulty. If done as an inquiry task, all students should be given clear and specific directions on how to write up the lab. Students in general, and ELL students in particular, might benefit from a simulated report example prepared by the teacher as a guide (particularly if they have limited experience with inquiry lab reports). Notes to Teacher Suggestions to implement this activity through an inquiry approach 1. You may wish to use cheaper and less breakable band tensioning devices than the bottles or beakers recommended in the original experiment. Bent clothes hangers or strips of wood should work OK. The jars were recommended in the original experiment because they distribute the tension equally around the band, so damage should be uniform. The disadvantage of this approach is that only one side of the band is exposed to the air. Simple wire and wood hangers will maximize exposure, making changes obvious in a shorter period of time. Even in potentially polluted areas, however, the students should allow 48 hours for ozone damage to become apparent. 2. Use any acceptable form of a lab write-up or oral lab report. Students should have the opportunity to explain what the question is and why it's important, describe in detail their experimental procedure, report their results in text and graphic form (graphs, tables), and explain how the data they collected answers the question. An example lab write-up format (intended for 9th grade students) is appended. Example Lab Report Format In this class we will frequently be doing labs that you design and carry out on your own. For these labs, you will turn in a report, either on paper or on disk (your choice), that follows the following format: 1. TITLE: The title should specifically describe what the lab is about ("The effect of insecticides on plant growth," not "Chemicals and plants"). 2. INTRODUCTION: Tell the reader why you are doing the study. Give enough background information so the reader will understand why the subject and the study is important. Tell the reader what you are trying to figure out in the form of a clear, logical, and answerable question. 3. MATERIALS: List all the supplies that you used so someone else could use exactly the same materials when repeating your study. 4. PROCEDURE: Pretend your lab is like a recipe and that you are writing for a reader not as smart as you. You have to describe exactly what to do and how to do it or the reader will probably mess it up. Procedures are best written in a numbered list (step 1, step 2, etc.) rather than in paragraph form, but if you like the paragraph form and can write very clearly, you may use it. If you've done it correctly, a younger student ought to be able to follow your instructions. Drawings or diagrams are often helpful. Be sure to identify CONTROL treatments and REPLICATES clearly in your procedure. 5. RESULTS: Data can take many forms, but it all needs to be clearly shown to the reader. You may use drawings, tables, or graphs, depending on what you are trying to show, but all have to be very well labeled, with titles and all units shown. You must also write in paragraph form what you found. This is where you draw the reader's attention to the most important or useful parts of your data. We will discuss these issues further in class. 6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION: This is the heart of the lab! Plan to spend LOTS of time on this section! This section should be written in paragraph form, not in a list. There are several parts to a good discussion section: a. Summarize why you did the lab and how you did it. b. Summarize what you found. c. Relate your findings specifically back to your purpose or question. Did you fulfill the purpose, answer the question? (It's totally OK if the answer is no; many experiments don't turn out to be what we expect them to be.) Either way, explain why. d. Discuss sources of error: These are things that you couldn't control—faulty equipment, limits on time or resources, other things you didn't plan on. Don't copout by just reporting that you messed up. e. If I wanted to pursue this research, what would you recommend that I do next? Leave me with a sense of where the research would go from here. Name: Period: Ozone Attack Background You've already learned in class that the substance known as ozone ( ) can be found high in the stratosphere where it serves to protect the earth's surface from high-intensity solar ultraviolet radiation. You've also learned that ozone can be found near ground level, a product of chemicals that comprise 'smog.' As a component of the lower atmosphere, it can cause significant damage to living things and some man-made materials. Simple rubber bands, under tension, can indicate the presence of ozone. Because ozone attacks and weakens the molecular bonds between the molecules that make up rubber, the bands become cracked and brittle upon exposure to ozone. In this investigation, you will use the degradation of rubber bands as an indicator of ozone as you survey areas for the presence of ozone. Procedure 1. You will be provided with a standard set of rubber bands and objects to stretch and hold the bands. (SEE NOTE #1 TO TEACHER) 2. Working alone or with a partner according to your teacher's directions, think about where you might expect to find high ozone concentrations and why, based on what you've learned about ozone. Develop a plan to determine whether or not these areas have high ozone concentrations as compared to other areas of potentially lower ozone, using the rubber band tests. In designing the study you will have to decide how long to run the test, where to place the rubber bands, and how you will measure and compare any possible ozone effects on the bands. In all these studies, be sure to only place the bands in shaded locations. If exposed to the sun, the direct action of solar UV on the bands can cause damage that resembles ozone damage. In order to design a good investigation, remember to always set aside one (or more) rubber band tests to be placed in an area of certain low (or zero) ozone concentration (in a zip-lock bag in a dark cupboard, for example, or sealed in a bottle with some activated charcoal to absorb any ozone that may be present in the air). 3. Show your experimental design to your teacher for approval before you proceed, then carry out the experiment, taking careful notes on what you do, how you do it, and the data that you collect. 4. Report the results of the study according to your teacher's instructions. Observations and Questions 1. Make drawings and a table describing the observable changes in the rubber bands. 2. Which location showed the greatest changes? Which location showed the least changes? 3. On which day did you first see noticeable changes? 4. Did all the rubber bands change on the same day? 5. What do you think may have caused the change in the rubber bands? 6. What might explain why you observed different degrees of change in various locations? 7. What do you think the effect on the rubber bands might suggest about any possible effect of ozone on living tissue, such as plants or your own lungs? 8. Describe in a short paragraph why your data might suggest possible hazards to people who work in copy rooms.