Tourism in a small historic city – Venice

advertisement

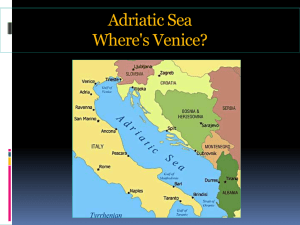

IB Geography @ IST – Tourism at a local scale Urban Area - Venice Tourism in a small historic city – Venice Venice is world famous as the only amphibious city. It developed towards the end of the Roman Empire and has a long history associated with a seafaring race, the Venetians, who created this small historic city, full of cultural antiquities including its world-famous fifteenth-century Renaissance art. It also has a long tradition of tourism, epitomized by the rich and leisured classes who visited in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. What makes Venice unusual and popular with visitors is its location on a series of islands in a lagoon (Figure 21.1), serving as the capital of the Veneto region of Italy. Despite economic growth in the region since the 1960s, the historic city of Venice experienced continued population loss during this period, dropping from 175 000 people in 1951 to now under 78 000. At the same time, many of the city’s historic buildings are under constant threat from the sea (Image 21.2) although this is not new and debates in the Victorian period saw poets such as Ruskin debating the modernizing influence of industrialization on the romantic aspects of the city. Among the main environmental threats facing Venice are a sinking ground level, a rising sea level, periodic flooding of the lagoon in which it is located and atmospheric pollution which impacts upon the foundations of its buildings and the very building fabric. But one of the most visible and persistent issues is the effect of tourism. As one of the city’s prominent residents whose popular BBC Television series – Venice, outlined: Building gondolas, rowing them, blowing glass and fashioning masks were once essential livelihoods in the economy of a great city: now they merely capitalize on the tourist industry although the very layout of the city [Figure 21.1], its canal structure and intimate urban landscape make it one of the most memorable cultural tourism experiences in Europe (Mosta 2004: 204). The scale of tourism is apparent from Mosta’s observation that: A reputed 15 million visitors flock to the city every year…and the cultural distinctiveness of Venice are threatened by the intense pressures of mass tourism. Cruise ships bring tourists right into the heart of Venice. There is much concern that this is damaging the fragile infrastructure of the city (Mosta 2004: 206). These visitor numbers are swelled by a large day-visitor market from other parts of Italy, especially the Adriatic beach resorts and Alpine areas and the concentration at key points such as St Mark’s Square (Image 21.3). Montanari and Muscara (1995) recognized that Venice was saturated at key times in the year (e.g. Easter) and that the police have had to close the Ponte del Liberta temporarily since the optimum flow of 21 000 tourists a day has been exceeded (e.g. 60000 at Easter and 100000 in the summer). The diversity of people attracted to the city is evident from Montanari and Muscara’s (1995) nine-fold classification of tourists: l first-time visitors on an organized tour l the rich tourist l the lover of Venice l the backpacker camper l the worldly-wise tourist l the return tourist l the resident artist l the beach tourist l the visitor with a purpose. Whilst excursionists comprise over 85 per cent of all visitors to the city, additional pressures have arisen by making the destination more accessible through the advent of low-cost airlines. Since the opening up of eastern Europe, the city has also seen an influx of eastern Europeans, with city officials reporting 60 000 Czechs arriving in 1200 coaches in one day. In Venice, van der Borg, Costa and Gotti (1996: 314) calculated the visitor:resident (host) ratio of 89.4:1 which may explain why residents may feel besieged by the tourists. The large volume of visitors who descend on Venice each year not only exceeds the desirable limits of tourism for the city but also poses a range of social and economic problems for planners. As van der Borg (1992: 52) observes the negative external effects connected with the overloading of the carrying capacity are rapidly increasing, frustrating the centre’s economy and society … excursionism [day tripping] is becoming increasingly important, while residential tourism is losing relevance for the local tourism market … [and] … the local benefits are diminishing. Tourism is becoming increasingly ineffective for Venice. A number of positive measures have been enacted to address the saturation of the historic city by day visitors including denying access to the city by unauthorized tour coaches via the main coach terminal. Glasson et al. (1995: 116) summarize the problem of seeking to manage visitors and their environmental impact in Venice: every city must be kept as accessible as possible for some specific categories of users, such as inhabitants, visitors to offices and firms located in the city, and commuters studying or working in the city. At the same time, the art city needs to be kept as inaccessible as possible to some other user categories (the excursionist/day-trippers in particular). The city has a well-developed heritage of traditional festivals and events (see below) and these attract more cultural tourists. The city’s heritage includes a number of more sustainable transport solutions to cater for the tourist market including the gondola (Image 21.6). This Insight is significant in that it highlights the prevailing problems affecting many historic cities around the world which are not peculiar to Venice. Whilst pollution is a grave problem for Venice, the greatest threat are day trippers who contribute little to the economy. Yet, as the example of Venice shows, it takes a determined political will to address the pressures posed by tourism since vested interests do not want to see the economy decline if visitors are not attracted. The launch of the Venice Card in 2004 is to control tourism, giving visitors priority via pre-booking, and to manage visitor numbers. It will need one million subscribers a year to work, so visitor numbers can be limited to 25 000 a day when on some days 200 000 arrive (Van der Borg 2004). Probably the greatest dilemma is in reaching a sustainable solution – a balance which is poignantly voiced by Mosta (2004: 211): ‘The future of Venice is uncertain. I hope that its remarkable history will be preserved along with its monuments, and that a balance can be found between opening up this city of wonders for modern visitors and restoring the integrity and vitality of the Venetian population’ in view of the declining resident population base and prevailing concerns that the city will eventually become a peopleless museum or devoid of Venetians as second home owners buy apartments. In such a case it would lose much of its appeal as a living and working city. The Environmental Impact of Tourism in Venice Venice is an internationally renowned tourist destination and a fine example of small historic city, with its cultural antiquities and highly acclaimed fifteenth century renaissance art. Venice is located on a series of islands in a lagoon, and is the capital of the Vento region of Italy, which has experienced massive economic growth since the 1960s. However, the historic city of Venice experienced continued population loss during this period, dropping from 175,000 in 1951 to 78,000 in 1992 and receives 47,000 commuters daily (Glasson et al. 1995). The age and condition of many of Venice's buildings are under constant threat. The environment in Venice is suffering from: • • • • a sinking ground level (Nagy 2000); a rising sea level (Penning – Rowsell et al. 1998); pollution of the lagoon in which it is located; atmospheric pollution (Zilio – Grandi and Szpyrkowicz 2000). One can also add to a further category to these environmental problems - tourism. As a tourist destination, visitor arrivals have developed from 50,000 tourists spending 1.2 million bednights in the historic city of Venice in 1952. By 1987 these figures had risen to 1.13 million tourist arrivals and 2.49 million bednights and 1.21 million arrivals and 2.68 million bednights in 1992. The average length of stay was 2.21 nights in 1992 (van der Borg et al. 1996). The number of hotel beds has grown from 20,000 in 1973 to 22,200 in 1992. These visitor numbers are swelled by a large day visitor market from other parts of Italy, especially the Adriatic beach resorts and Alpine areas. In 1992, the day-tripper market was estimated to be 6 million visitors providing a total market in excess of 7 million visitors a year. Much of this growth in demand has been motivated by a desire to experience and understand the city’s cultural heritage (Costa and van der Borg 1992; van der Borg 1994; van der Borg et al. 1995, 1996). Montanari and Muscara (1995) recognised that Venice was saturated at key times in the year (e.g. Easter) and that the Police have had to close the Ponde del Liberta since the optimum flow of 21,000 tourists a day has been exceeded (e.g. 60,000 at Easter and 100,000 in the summer). The challenge posed by visitors was well illustrated in July 1989 when the pop group Pink Floyd held a concert which attracted 200,000 visitors and pushed the City’s infrastructure to the limit. Since 1987, on selected spring weekends, the land route from the mainland to Venice has been closed to visitors as an extreme form of crisis management (Montanari and Muscara 1995). Montanari and Muscara (1995) developed a nine-fold classification of tourists based on differences in their spatial behaviour, perception and spending power which can be summarised thus: The first time visitors on an organised tour The rich tourist The lover of Venice The backpacker camper The worldlywise tourist The return tourist The resident artist The beach tourist The visitor with a purpose reflecting the unique tourism environment (Fiorelli 1989) and the diversity of motivations for visiting the city. What is notable in the case of Venice is the dominance of excursionists (83.1%) in comparison to tourists (16.9%) (van der Borg et al. 1996) which exhibits a very even pattern of distribution throughout the year. In the first quarter (January – March) 14% of visitors arrive followed by 30% (April – June), 32% (July – September) and 24% (October – December). The destination’s accessibility has also been increased with the recent advent of low-cost airlines in Europe, following the liberalisation of air transport regulations (Mason 2000), with the growth in leisure travel noted in Chapter Three. Venice’s tourist market is comprised of 26.3% of arrivals from within Italy, 36% from Europe, 17.7% from the USA, 11.1% from Japan and 8.8% from other countries/regions. The social impact of the existing patterns of demand led van der Borg et al. (1996: 314) to calculate the visitor/resident (host) ratio for Venice and a number of other European heritage cities. In Venice’s historical centre, a ratio of 89.4:1 existed while for the wider Venice municipality this dropped to 27.6:1. This level of visitor pressure reflects the scale of the problem facing Venice (see Costa 1990), with only Bruges recording a level of 36:1, in excess of Venice’s municipality. Both van der Borg et al. (1996) and Jansen-Verbeke and Lievois (1999) refer to the term ‘touristification’ of the urban area, since at key points / attractions in the city, major pressure points exist where locals are greatly outnumbered by tourists and excursionists. In fact, Venice has constructed a number of hotels in the suburbs to host commuting tourists (van der Borg 1991) as one way of spreading ‘tourist pressure’. While the demand and supply of urban tourism in Venice is extensively documented by van der Borg (1991), and van der Borg and Costa (1993), it is Canestrelli and Costa's (1991) attempt to calculate the carrying capacity using a mathematical model - linear programming - which offers a number of insights into the carrying capacity of Venice as a tourist destination. Venice's Carrying Capacity To assess the carrying capacity of the historic centre of Venice, Canestrelli and Costa (1991) established: • • • • the historic centre of Venice comprises 700ha, with buildings protected from alterations by government legislation; the resident population and extent of daily commuting into and out of the city; the optimal use level of the destination using a range of variables such as supporting facilities (e.g. hotels, restaurants and parking spaces) and those variables describing the nature of the users (e.g. categories of tourist); the local tourist-dependant and non-tourist dependant population in the locality and the theoretical relationship which exists between tourists and these two sub-groups. Each group also seeks to maximise their own position. For example, the tourist-dependant population will seek to push the tourist carrying capacity up as they derive economic benefits from visitor spending, but residents not dependent on tourism are likely to try and minimise the number of visitors to reduce the costs of tourism. Using a linear programming technique (see Canestrelli and Costa 1991 for full details of the mathematical model and its application), the optimal growth of Venice as a tourist destination was explored. According to Canestrelli and Costa (1991) the optimal carrying capacity for the historic city of Venice would be to admit 9780 tourists who use hotel accommodation, 1460 tourists staying in nonhotel accommodation and 10,857 day trippers on a daily basis. One important consideration is that tourism demand is seasonal, although less so for urban destinations with their all year round attractions. Nevertheless, if the 4.1 million day trippers who visit Venice were evenly spread this would still amount to 11,233 trippers a day. In fact research has estimated that an average of 37,500 day trippers a day visit Venice in August. Canestrelli and Costa (1991) argue that a ceiling of 25,000 visitors a day is the maximum carrying capacity for Venice. This has important implications for the environment and its long term preservation if the carrying capacity is being exceeded. Obviously, the ecological and economic carrying capacity are likely to have slightly different values, but the 25,000 threshold provides an indication of the scale of tourism that is desirable in an ideal world. Yet the reality of the situation is very different: van der Borg and Costa (1993) observe that in 1987, on 156 days a year this number was exceeded. On 22 occasions 40,000 visitors a day visited Venice and on 6 days the visitor numbers exceeded 60,000. So what are the implications for the future? According to a variety of tourism forecasts produced by van der Borg (1992) for the year 2000, the critical threshold of 25,000 visitors will be exceeded on 216 days and on 7 days the visitor numbers will exceed 100,000 if the current growth rate in arrivals continues. In fact when 100,000 visitors fill the city, the local police close the bridge connecting the historic centre with the mainland for safety reasons. But the large volume of visitors which descend on Venice each year not only exceeds the desirable limits of tourism for the city, but also poses a range of social and economic problems for planners. As van der Borg (1992: 52) observes the negative external effects connected with the overloading of the carrying capacity are rapidly increasing, frustrating the centre's economy and society ... excursionism [day tripping] is becoming increasingly important, while residential tourism is losing relevance for the local tourism market ... [and] ... the local benefits are diminishing. Tourism is becoming increasingly ineffective for Venice. Thus, the negative impact of tourism on the historic centre of Venice is now resulting in a selfenforcing decline as excursionists, who contribute less to the local tourism economy than staying visitors (Glasson et al. 1995: 113), and supplant the staying market as it becomes less attractive to stay in the city. Ironically, changing the attitude of the city's tourism policy-makers is difficult: it is heavily influenced by the pro-tourism lobby while hotel owners have sought to get the city council to restrict the booming eastern European day trip market which contributes little to the tourism economy. A number of positive measures have been enacted to address the saturation of the historic city by day visitors including denying access to the city by unauthorised tour coaches via the main coach terminal. Even so, the city continues to promote the destination thereby alienating the local population. One also has to recognise the environmental processes which affect both the local and tourist population, namely flooding. Flooding in Venice now means that St Mark’s Square, an icon for visitors, floods 40-60 times a year compared to 4-6 times a year at the beginning of the twentieth century. As a result, tourism has to be balanced with measures of environmental protection and management (Nagy 1999). A range of positive steps are needed to provide a more rational basis for the future development and promotion of tourism in the new millennium (see van der Borg 1992; Glasson et al. 1995 for more details). Glasson et al. (1995: 116) summarise the problem of seeking to manage visitors and their environmental impact in Venice: … every city must be kept as accessible as possible for some specific categories of users, such as inhabitants, visitors to offices and firms located in the city, and commuters studying or working in the city. At the same time, the art city needs to be kept as inaccessible as possible to some other user categories (the excursionist / day-trippers in particular) (Glasson et al. 1995 : 116). What the example of Venice shows is that while tangible economic benefits accrue to the city, the social and environmental costs are very substantial. Montanari and Muscari (1995) argued that the Venice water transport plays a major role in tourism within the city which can be used to manage visitors, while the city needed to plan to separate the access, circulation and exit of the resident / commuting population and tourists. Clearly, Venice is a small historic city under siege from a new marauding army in the early twentyfirst century: the tourist and excursionist. In this case, tourism has not been a stimulus for urban growth, but has actually contributed to urban decline as residents have continued to leave. The excessive numbers of day-trippers have also led to a deterioration in the quality of the tourist experience. This case study is significant in that it highlights the prevailing problems affecting many historic cities around the world, especially those in Europe. But it takes political will to embark on a decision-making process which will address the pressures posed by tourism in Venice. The carrying capacity of any tourist city needs to be carefully examined and if quantitative techniques, such as linear programming, help to establish an independent and authoritative basis for future planning, then it is a useful starting point in helping to reach a symbiotic balance between tourism and the urban environment. Otherwise a situation may develop which is characterised by conflict. The management of the environment of tourist cities is equally as important as in sensitive rural environments even though urban areas have attracted less attention among researchers.