Chapter 4 - Constitutional Authority to Regulate Business

advertisement

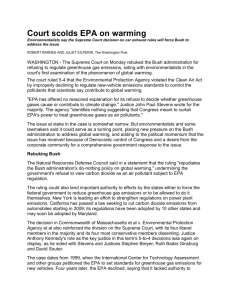

BLTC-9e Case Problem with Sample Answer Chapter 38: Administrative Law 38–6 Case Problem with Sample Answer A well-documented rise in global temperatures has coincided with a significant increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Many scientists believe that the two trends are related, because when carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, it produces a greenhouse effect, trapping solar heat. Under the Clean Air Act (CAA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is authorized to regulate “any” air pollutants “emitted into . . . the ambient air” that in its “judgment cause, or contribute to, air pollution.” A group of private organizations asked the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse gas” emissions from new motor vehicles. The EPA refused, stating that Congress last amended the CAA in 1990 without authorizing new, binding auto-emissions limits. The petitioners—nineteen states, including Massachusetts—asked a district court to review the EPA’s denial. Did the EPA have the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from new motor vehicles? If so, was its stated reason for refusing to do so consistent with that authority? Discuss. [Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, __ U.S. __, 127 S.Ct. 1438, 167 L.Ed.2d 248 (2007)] Sample Answer: The United States Supreme Court held that greenhouse gases fit within the Clean Air Act's (CAA’s) definition of “air pollutant.” Thus, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has the authority under that statute to regulate the emission of such gases from new motor vehicles. According to the Court, the definition, which includes “any” air pollutant, embraces all airborne compounds “of whatever stripe.” The EPA's focus on Congress’s 1990 amendments (or their lack) indicates nothing about the original intent behind the statute (and its amendments before 1990). Nothing in the statute suggests that Congress meant to curtail the agency’s power to treat greenhouse gases as air pollutants. In other words, the agency has a pre-existing mandate to regulate “any air pollutant” that may endanger the public welfare. The EPA also argued that, even if it had the authority to regulate greenhouse gases, the agency would not exercise that authority because any regulation would conflict with other administration priorities. The Court acknowledged that the CAA conditions EPA action on the agency’s formation of a “judgment,” but explained that judgment must relate to whether a pollutant “cause[s], or contribute[s] to, air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” Thus, the EPA can avoid issuing regulations only if the agency determines that greenhouse gases do not contribute to climate change (or if the agency reasonably explains why it cannot or will not determine whether they do). The EPA’s refusal to regulate was thus “arbitrary, capricious, or otherwise not in accordance with law,” The Court remanded the case for the EPA to “ground its reasons for action or inaction in the statute.”