Unknown Chemical Exposure - Virginia Department of Health

advertisement

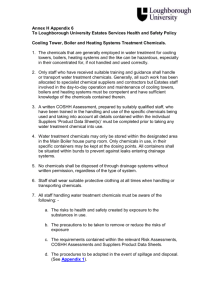

Virginia Department of Health Unknown Chemical Exposure: Overview for Healthcare Providers Agent/ Characteristics Potential Sources Route of Exposure Contamination/ Decontamination Risk Indicators Cause of Death Latency Clinical Manifestations Laboratory Tests/ Sample collection Radiography Treatment Precautions/ Disposition Notification Thousands of chemicals have the potential to harm humans. Chemicals that form vapor or exist in a gaseous state are most likely to spread from a source and may harm large numbers of people. Most people injured in large chemical accidents (HazMat) are harmed by inhaled toxins. Liquids and solids that do not form vapor can cause harm by direct contact. Odor is not a reliable indicator of toxicity. Industrial and agricultural chemicals manufactured, used, stored or transported are vulnerable to accidental or intentional release. Terrorist groups may be able to manufacture/acquire harmful chemicals. Inhalation (most common); dermal absorption; ingestion of tainted food or water supplies. Contamination: People with skin or clothing contamination can expose others (including healthcare providers) by direct contact or through off-gassing vapor. Clothing carrying chemical vapor poses a greater risk of secondary contamination than skin. Decontamination: For patients exposed only to vapor, remove outer clothing and wash exposed areas including the head and hair with soap and water. For patients exposed to harmful liquid chemicals, remove all clothing and wash entire body and hair with soap and water. Extent of injury depends on the concentration and duration of exposure. Chemical exposure may exacerbate underlying chronic diseases. Those with reactive airways disease, chronic pulmonary diseases, or cardiovascular disease are more susceptible to smaller exposures and may have serious effects. Children and the elderly are more susceptible to harmful chemicals. Harmful chemicals may cause death from acute toxic effects such as respiratory failure from direct pulmonary injury, cardiac dysrhythmias or apnea from coma or muscle paralysis. Delayed death (hours to days after exposure) may be due to pulmonary, CNS, bone marrow, liver, or renal complications. Many harmful chemicals cause immediate clinical effects such as burning mucous membranes, skin burns, mental status changes or respiratory complaints. Some chemicals have delayed onset of effects (hours to days). Skin contact with a harmful liquid is often slower to cause systemic toxic effects than inhalation of the same chemical in a vapor state. Many chemicals cause distinct clinical manifestations that may guide empiric treatment decisions until confirmatory evidence of the chemical’s identity is available. Irritant gas exposure: Mucous membrane irritation, burning chest pain, cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. Pesticide-like poisoning/nerve agents: Pinpoint pupils, SLUDGE (salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, GI complaints, emesis), coma, seizures, flaccid paralysis, and muscle twitching. Acute solvent exposure: Strong chemical odor is often noted, mucous membrane irritation, nausea, headache, dizziness, anxiousness, dyspnea, chest tightness, syncope, seizures or coma. Knock-down: Abrupt onset of profound toxic effects such as syncope, seizures, coma, gasping respirations, and cardiovascular collapse, potentially causing death within minutes. Chemical burns: Erythema, blisters, and necrosis. Different than thermal burns because chemicals can enter the systemic circulation and cause toxic effects distant from the skin. Acute radiation-like illness: Delayed onset of nausea, vomiting, skin, lung and bone marrow effects. Other organ systems may be affected. Other: Not all chemicals can be classified into a simple toxic syndrome category. For example, some chemicals may cause delayed neurological, pulmonary, or other end-organ effects. Confirmatory diagnostic testing is NOT available for most poisonings. Routine laboratory data should be obtained as indicated and when adequate resources are available. Obtain routine radiography as indicated by clinical presentation. Treat the patient, NOT the poison. Supportive care and treating easily correctable problems is the mainstay of therapy. Antidotes are available for only a few specific poisonings (e.g., pesticide-like/nerve agent poisonings require urgent treatment with atropine plus pralidoxime, or Mark I kit(s); cyanide poisoning requires a cyanide antidote kit). Empiric treatment may be guided by recognizing distinct clinical syndromes long before confirmation of a specific chemical agent. Pitfalls: Not recognizing that the cause of a patient’s illness is chemical-induced. Not recognizing a contaminated patient with a risk of secondarily contaminating others. Focusing on the chemical identification instead of treating the patient’s symptoms. All chemical exposures should be reported to the regional poison center at 1-800-222-1222. Outbreaks and unusual occurrences are reportable to your local health department. If this is a suspected emergency, report the incident to the local 911 center. For more information, refer to: Virginia Department of Health, www.vdh.virginia.gov/EPR/Agents.asp, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.bt.cdc.gov or www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/mmg172.html, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, http://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/bestpractices/firstreceivers_hospital.pdf Updated 08/04/2004