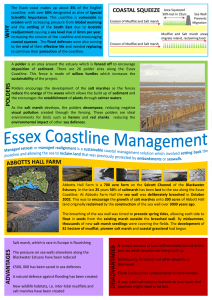

Drained Marsh strategy

advertisement