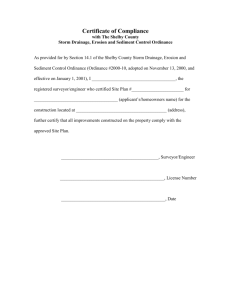

Stormwater Toolbox for Maintenance Practices

advertisement