Management of Chemical Environmental Risks

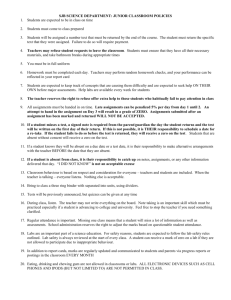

advertisement