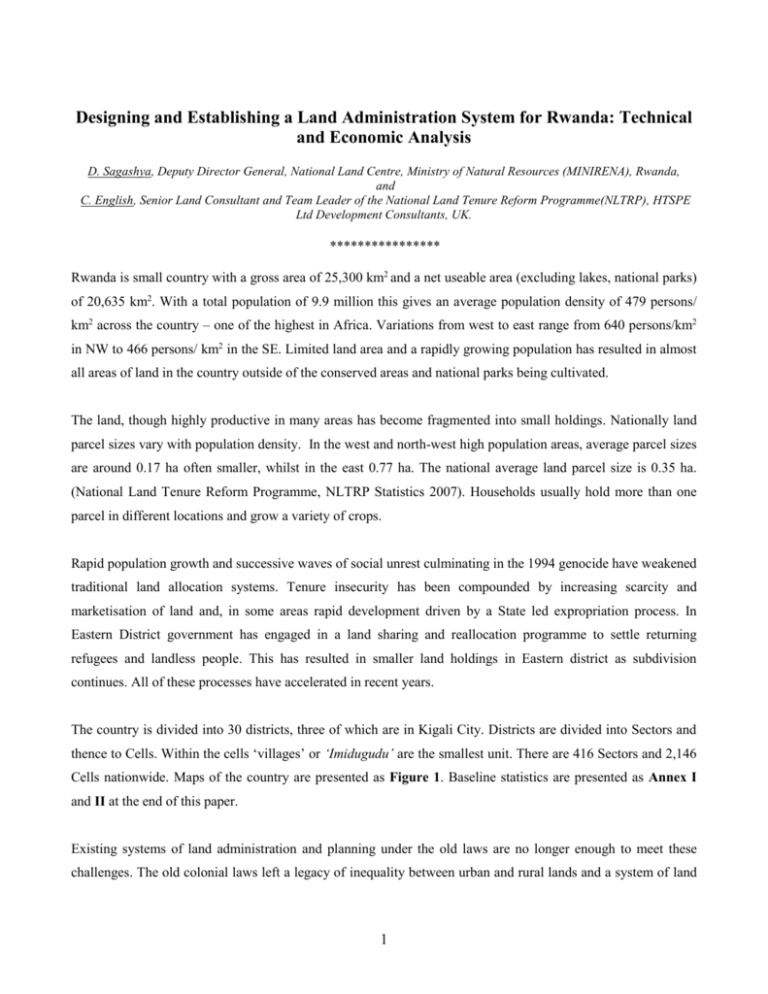

1.5 The Organic Land Law, 2005

advertisement