Analysis of Evaluation Approaches

advertisement

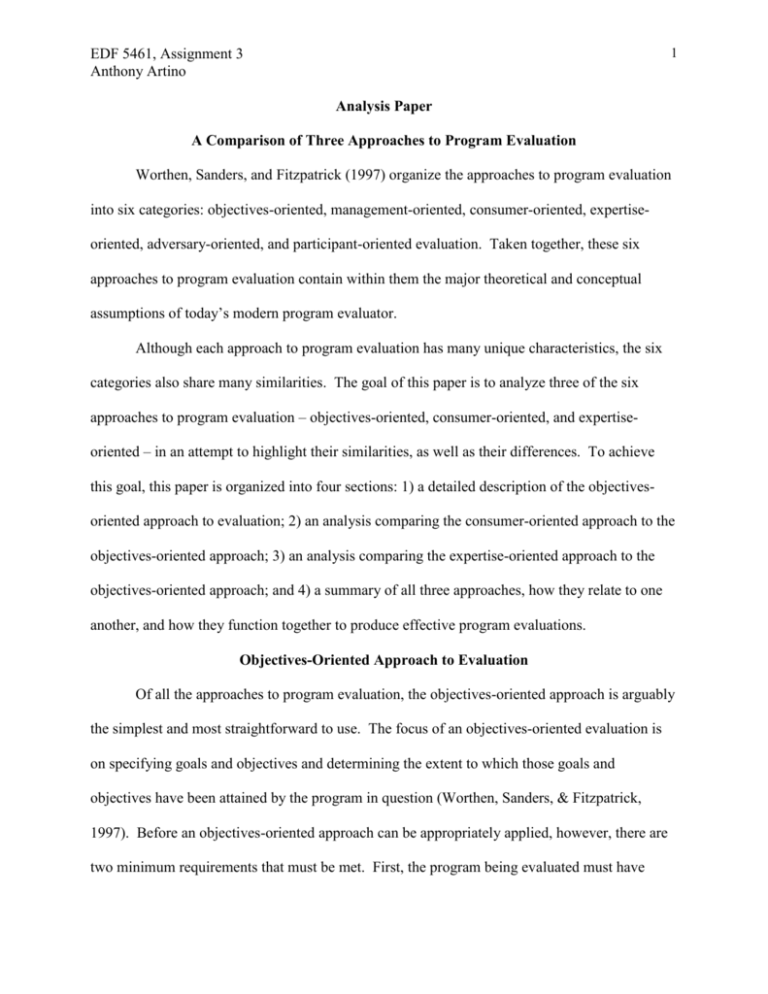

1 EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino Analysis Paper A Comparison of Three Approaches to Program Evaluation Worthen, Sanders, and Fitzpatrick (1997) organize the approaches to program evaluation into six categories: objectives-oriented, management-oriented, consumer-oriented, expertiseoriented, adversary-oriented, and participant-oriented evaluation. Taken together, these six approaches to program evaluation contain within them the major theoretical and conceptual assumptions of today’s modern program evaluator. Although each approach to program evaluation has many unique characteristics, the six categories also share many similarities. The goal of this paper is to analyze three of the six approaches to program evaluation – objectives-oriented, consumer-oriented, and expertiseoriented – in an attempt to highlight their similarities, as well as their differences. To achieve this goal, this paper is organized into four sections: 1) a detailed description of the objectivesoriented approach to evaluation; 2) an analysis comparing the consumer-oriented approach to the objectives-oriented approach; 3) an analysis comparing the expertise-oriented approach to the objectives-oriented approach; and 4) a summary of all three approaches, how they relate to one another, and how they function together to produce effective program evaluations. Objectives-Oriented Approach to Evaluation Of all the approaches to program evaluation, the objectives-oriented approach is arguably the simplest and most straightforward to use. The focus of an objectives-oriented evaluation is on specifying goals and objectives and determining the extent to which those goals and objectives have been attained by the program in question (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997). Before an objectives-oriented approach can be appropriately applied, however, there are two minimum requirements that must be met. First, the program being evaluated must have EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino 2 goals and objectives, and those goals and objectives, if broadly defined, must be sufficiently honed, sharpened, and clarified into measurable, behavioral objectives. Second, using appropriate measurement tools, performance must be measured and compared to those previously identified behavioral objectives. With these two requirements met, an evaluator’s job becomes one of identifying discrepancies between performance and objectives. In most cases, identification of program discrepancies leads to program modifications, which are intended to close the performance gap. Once modifications are made to a program, the program often undergoes another evaluation and the cycle is repeated (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997). The primary benefit associated with an objectives-oriented evaluation is simplicity. As Worthen and colleagues (1997) describe, an objectives-oriented approach “…is easily understood, easy to follow and implement, and produces information that program directors generally agree is relevant to their mission” (p. 91). Another strength of the objectives-oriented evaluation approach is its focus on outcomes (i.e. is the program doing what the designers intended for it to do?). A third and final benefit of the objectives-oriented approach, and one that might be considered a side effect, is that it often requires program directors to reflect on and further clarify the true goals and objectives of their program, which, prior to the evaluation, may have been vague or confusing. Although straightforward and easy to use, objectives-oriented evaluations do have their drawbacks and limitations. Of primary concern to many evaluators is the criticism that an objectives-oriented approach can sometimes focus too much on program goals and objectives, some of which may not be worth attaining in the first place, and not enough on making explicit judgments of a program’s worth. Put another way, a program’s performance may meet a specified goal or objective, but that does not necessarily mean the program is effective or EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino 3 efficient. In fact some critics argue that goals and objectives often act like blinders to an evaluator, causing him to narrow the focus of the evaluation, thereby neglecting important outcomes not specifically addressed by those goals and failing to see a program’s unintended and sometimes negative side effects (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997). Consumer-Oriented Approach to Evaluation – Similarities and Differences Consumers of educational and other human services products have used consumeroriented evaluations extensively. Characterized by criteria checklists that cover everything from cost-effectiveness to performance, a consumer-oriented approach emphasizes the use of stringent and defensible standards against which programs and products are judged. Although conceptually different, consumer-oriented evaluations do have some similarities to objectives-oriented evaluations. First, like an objectives-oriented approach, a consumer-oriented evaluation is fairly simple for most people to understand and use in practice. For example, using a consumer-oriented approach, an evaluator compares the program or product of interest against a list of criteria or standards. This type of assessment is not unlike an objectives-oriented approach where an evaluator uses a list of objectives against which he compares the performance of a program. In fact some experts in the field of evaluation have used the terms “standards” and “objectives” interchangeably, attesting to their similarities. Stake (as cited in Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997) noted “standards are another form of objectives: those seen by outside authority-figures who know little or nothing about the specific program being evaluated but whose advice is relevant to programs in many places” (p. 85). Another similarity between consumer and objectives-oriented evaluations is their objectivity, which makes them more unbiased and defensible than many other approaches. For instance, because both approaches use objective measures, like program objectives and standards, EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino 4 evaluator’s can feel comfortable standing behind their evaluation judgments, pointing to the objective measures used, and stating whether or not a program successfully met those criteria. Finally, both objectives-oriented and consumer-oriented approaches to evaluation have been criticized for being too narrow in focus. In the case of objectives-oriented evaluation, the limited focus on objectives can result in an oversimplified evaluation with an overemphasis on outcomes (vise overall program effectiveness). Similarly, with a consumer-oriented evaluation, the narrow focus on stringent standards can squelch creativity in the development process resulting in a dry, uninteresting product that meets the standards but is in no way innovative. One key difference between a consumer-oriented approach and an objectives-oriented approach is the audience for which the evaluation is primarily designed. In the case of an objectives-oriented approach, the evaluation is normally completed in an attempt to help program directors, developers, administrators, and funding agents determine the extent to which their program’s performance meets their program’s objectives. On the other hand, the primary audience for a consumer-oriented approach is the consumer of that program or product. In this case, the consumer is interested in determining if the program is effective and should be purchased; he is not necessarily interested in determining if the program’s performance meets its objectives. A second difference between the two approaches is the amount of front-end work that must be completed before the evaluation can be completed. With an objectives-oriented approach, the assessment part of the evaluation can only occur after the program’s goals and objectives have been stated and operationally defined (a process that can take a substantial amount of time). On the other hand, all one needs to begin a consumer-oriented approach is an evaluation checklist, a tool that has become increasingly easy to obtain with the popularity of consumer-oriented evaluations. EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino 5 Expertise-Oriented Approach to Evaluation – Similarities and Differences Expertise-oriented approaches to evaluation are probably the oldest and most widely used. They rely primarily on the opinions and expert judgments of professionals in the field being evaluated and are used extensively to evaluate everything from hospitals and pharmacies to peer-reviewed journal articles and schools. Although quite different in their structure and use, expertise-oriented evaluations do have some similarities to objectives-oriented evaluations. First, like an objectives-oriented approach, an expertise-oriented evaluation is easy to understand and relatively easy to implement. For example, an ad hoc panel review board can be organized in short order by gathering together the experts from a given field, providing them with some general guidance, and letting them use their best judgment to assess a program, product, or individual. Another similarity between objectives and expertise-oriented evaluations is standards. As already discussed, standards are sometimes considered another form of objectives. In the case of expertise-oriented evaluations, even if explicit standards do not exist (which is often the case with informal and ad hoc evaluations), the experts making evaluative judgments still possess their own understanding of what standards the program, product, or individual under review should meet. Put another way, experts have certain internal objectives, based on their expertise, against which they compare a program, product, or individual’s performance, thereby allowing them to make judgments and determine worth. For example, with an informal graduate student review board, “…committee members determine the standards for judging each student’s preparation and competence” (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997, p. 126). The primary and most apparent difference between an expertise-oriented evaluation and an objectives-oriented evaluation is the former’s “…direct, open reliance on subjective 6 EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino professional expertise as the primary evaluation strategy” (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997, p. 120). Although one could argue that all categories of program evaluation involve some amount of subjective professional judgments, an expertise-oriented approach is the only one that puts so much stock in the importance of professional expertise. It is because of this reliance on personal, expert opinion, that expertise-oriented evaluations are more prone to personal bias than the average objectives-oriented approach. Actually, some critics of the approach argue that judgments made by expert evaluators reflect little more than personal bias (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997). Moreover, expert-oriented peer-reviews have caused public suspicion and are considered by some to be “…inherently conservative, potentially incestuous, and subject to possible conflict of interest” (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997, p. 133). A second difference between expertise and objectives-oriented evaluations is their structure. Whereas an objectives-oriented approach has a very limited, objectives-only structure, an expertise-oriented approach can run the gamut – having a relaxed structure, a clearly defined structure, or something in between. For example, an informal review process may simply consist of a panel of experts who follow loosely defined procedures, with each member deciding what components of a program to consider and the standards against which those components will be judged. A formal accreditation committee, on the other hand, may have published standards and measurement instruments that are used faithfully for every evaluation. Summary The three approaches to program evaluation presented in this analysis share many characteristics. At the same time, all three approaches are conceptually different and, as such, diverge in many areas. Table 1 gives a visual representation of the analysis presented in the previous sections of this paper. The color-coded blocks in Table 1 illustrate characteristics 7 EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino shared by each approach, as well as those characteristics that set the three approaches to program evaluation apart. Table 1. Three Approaches to Program Evaluation – Similarities and Differences. Characteristic Objectives-Oriented Approach Consumer-Oriented Approach Expertise Oriented Approach Easy To Understand Yes Yes Yes Easy To Use Yes Yes Yes Defensible Judgments Yes Yes Can Be Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Fairly Unbiased Yes Yes Can Be Perceived as Unbiased Yes Yes No Fairly Biased No No Can Be Perceived as Biased No No Yes Narrow Focus Yes Can Be Can Be Broader Focus No Can Be Yes Used by Customers No Yes Can Be Yes Can Be Can Be Yes Can Be Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Highly Structured Yes Yes Can Be Moderately Structured No No Can Be Unstructured No No Can Be Use of Objectives/Standards Use of Subjective Measures Used by Program Participants Used by Funding Agencies Requires Lots of FrontEnd Work Requires Little FrontEnd Work EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino 8 Of the three approaches to program evaluation discussed in this analysis, not one exists by itself in a vacuum. Instead, each approach, with its strengths and weaknesses, can be combined with others to produce an effective program evaluation. Using what Worthen and colleagues (1997) call an “eclectic approach,” innovative evaluators tend to select and combine concepts from each approach to fit their particular situation. As Worthen et al. (1997) describe, “In very few instances have we adhered to any particular “model” of evaluation. Rather, we find we can ensure a better fit by snipping and sewing together bits and pieces off the more traditional ready-made approaches and even weaving a bit of homespun, if necessary, rather than by pulling any existing approach off the shelf. Tailoring works” (p. 183). For example, the United States military uses an eclectic approach to evaluation when qualifying officers in their warfare specialty. Specifically, in order to qualify for certain duties, officers must complete a job qualification requirement (JQR). This JQR is a checklist of behavioral objectives that must be met by the officer. To evaluate whether or not an officer has met these objectives, the officer’s performance is simply assessed against the JQR (i.e. an objectives-oriented approach is applied). The evaluation, however, does not stop there. Once the JQR is finished, the officer completes the qualification process by standing before a panel of community experts for his final review (i.e. an expertise-oriented approach is applied). This qualification process, which has been used for more than 200 years to qualify officers the in world’s greatest military, is a straightforward example of how multiple evaluation approaches can be strung together to create an effective evaluation process. Another example of how multiple evaluation approaches can be used together to produce effective program evaluation is the selection of educational software. An organization needing to choose from multiple software products might decide to use a product analysis checklist (i.e. a 9 EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino consumer-oriented approach) combined with an ad hoc panel review (i.e. an expertise-oriented approach). Using a product analysis checklist, the organization ensures each product is evaluated against well-established standards. At the same time, the ad hoc panel, consisting of individuals with specific knowledge of the organization, ensures the winning product fits with the organization’s strategic goals. By approaching product analysis from this eclectic perspective, organizations benefit from the strengths of each evaluation model while at the same time minimizing the negative effects associated with individual approach limitations. Conclusion The purpose of this analysis was to compare and contrast three approaches to program evaluation – objectives-oriented, consumer-oriented, and expertise-oriented. It was not intended to imply that any one of the three approaches is better than any other. Rather, by understanding the similarities and differences between the three methods, it is hoped that program evaluators can be more effective in their application of multiple evaluation approaches. Ultimately, the success of any evaluation depends, in large part, on the evaluator’s understanding of the different approaches and his ability to “…determine which approach (or combination of concepts from different approaches) is most relevant to the task at hand” (Worthen, Sanders, & Fitzpatrick, 1997, p. 182). 10 EDF 5461, Assignment 3 Anthony Artino References Worthen, B.R., Sanders, J.R., Fitzpatrick, J.L. (1997). Program Evaluation: Alternative Approaches and Practical Guidelines. (2nd Ed). White Plains, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.