Chap5-3

advertisement

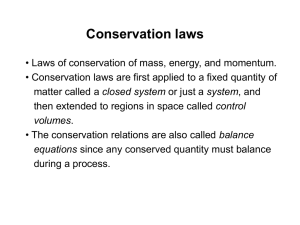

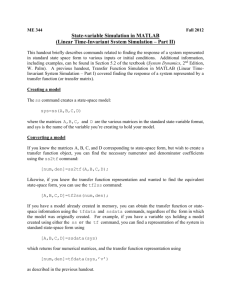

Chapter 5 5.3 Macroscopic Energy Balance The general energy balance equation has the form Input Output Heat Accumulation = + of Energy of Energy of Energy to added Work System by done System Let Esys be the total energy (internal + kinetic + potential) of a system, m in be the mass flow rate of the system input stream, and m out be the mass flow rates of the system output stream, then 2 d U sys Ek ,sys E p,sys = m in uin Vin gzin m out dt 2 V2 uout out gzout + Q W (5.3-1) 2 where Usys = system internal energy Ek,sys = system kinetic energy Ep,sys = system potential energy uin , uout = internal energies per unit mass of the system inlet and outlet streams Vin , Vout = average velocity of the system inlet and outlet streams Q = rate of heat added to the system W = rate of work done by the system The net rate of work done by the system can be written as W = W s + W f where W s = rate of shaft work = rate of work done by the system through a mechanical device (e.g., a pump motor) W f = rate of flow work = rate of work done by the system fluid at the outlet minus rate of work done on the system fluid at the outlet Pin Pout distance = Force velocity velocity Rate of flow work done on the system fluid = PinAinVin = Pin Fin Rate of work = Force 5-9 Rate of flow work done by the system fluid = PoutAoutVout = Pout Fout Eq. (5.3-1) becomes d Vin2 U sys Ek ,sys E p,sys = m in uin gzin m out dt 2 + Q W + Pin F Pout F s in 2 Vout uout gzout 2 out (5.3-2) The internal energy can be combined with the flow work to give the enthalpy P in Fin uin + Pin Fin = in Fin uin in = in Fin hin in In terms of enthalpies hin and hout 2 d U sys Ek ,sys E p,sys = m in hin Vin gzin m out dt 2 V2 hout out gzout + Q W s (5.3-3) 2 The internal energy and the enthalpy can be related to the heat capacities where h Cp = , and Cv = T p u T v For constant values of Cp and Cv h = Cp(T - Tref) and u = Cv(T - Tref) For solid and liquid Cp Cv = m in = m out , equation If the system is at steady state with one inlet and one exit stream m (5.3-3) is simplified to hout hin + g(zout zin) + W 1 2 Q Vout Vin2 = s 2 m m (5.3-4) W Q , w = s be the heat added to the system and work done m m by the system, respectively, per unit mass flow rate. Equation (5.3-4) becomes Let = (“out”) (“in”), and q = h + gz + 1 V2 = q w 2 (5.3-5) 5-10 This equation also applies to a system comprising the fluid between any two points along a streamline within a flow field. If these two points are only infinitesimal distance apart, the differential form of the energy equation is obtained dh + gdz + VdV = q w (5.3-6) The d() notation represents a total or “exact” differential and applies to the change in state properties that are determined only by the initial and final states of the properties. The () notation represents an “inexact” differential and applies to the change in properties that depend upon the path taken from the initial to the final point of the properties. The forms of energy can be classified as either mechanical energy, associated with motion or position, or thermal energy, associated with temperature. Mechanical energy is considered to be an energy form of higher quality than thermal energy since it can be converted directly into useful work. Mechanical energy includes potential energy, kinetic energy, flow work, and shaft work. Internal energy and heat are thermal energy forms that cannot be converted directly into useful work. For systems that involve significant temperature changes, the mechanical energy terms are usually negligible compared with the thermal terms. In such cases the energy balance equation reduces to a “heat or enthalpy balance”, i.e. dh = q. Example 5.3-1. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------In a residential water heater, water at 60oF flows at a constant 5 GPM into the 100 gallons tank and leaves at 3 GPM. Initially the tank has 10 gallons of 75oF water in it. The tank gas heater heats the tank contents at a constant rate of 800 Btu/min. Assume perfect mixing, determine the temperature of the discharge water after 20 min. of operation. Water: Cp = Cv = 1 Btu/(lb.oF), density = 62.4 lb/ft3. Unit conversion 1 ft3 = 7.481 gal. Fo , To Q F, T Solution -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Step #1: Define the system. Step #2: Find an equation that contains the temperature of the discharge water. The energy balance for the system gives the desired equation. 5-11 Step #3: Apply the energy balance on the system with the reference temperature Tref = 0oF. Neglect the changes in kinetic and potential energies compared with the changes in thermal energies. d (VCpT) = FoCpTo - FCpT + Q dt d Q (VT) = FoTo - FT + dt C p dV = 5 - 3 = 2 => V = 10 + 2t dt Step #4: Specify the initial condition for the differential equation. At t = 0, T = 75oF Step #5: Solve the resulting equation and verify the solution. V Q dT dV + T = FoTo - FT + C p dt dt (10 + 2t) dT (800)( 7.481) + 2T = (5)(60) - 3T + dt (62.4)(1) (2t + 10) dT = 395.91 - 5T dt dT 75 395.91 5T = T dt t 395.91 5T 1 2t 10 - 5 ln 395.91 5 75 = 0 2t 10 395.91 - 5T = 20.91 10 2 . 5 1 2t 10 ln 2 10 2t 10 => T = 79.182 - 4.182 10 2 . 5 at t = 20 min., T = 79.1oF ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Equation (5.3-5) and its differential form, equation (5.3-6), are not convenient for solving engineering problems. 1 V2 = q w 2 (5.3-5) dh + gdz + VdV = q w (5.3-6) h + gz + 5-12 We can use thermodynamics relations to convert the enthalpy term into a form that involves temperature, pressure, and density changes across the system. du = Tds Pd(1/) dh = du + d(P/) = Tds Pd(1/) + d(P/) dh = Tds Pd(1/) + Pd(1/) + dP = Tds + dP (5.3-7) For an idealized reversible process in which no energy dissipation occurs, the entropy change arises from heat transfer across the system boundaries Tds = q In any real system, the process is irreversible and there is dissipation of energy, therefore Tds = q + ef = du + Pd(1/) dh = q + ef + (5.3-8) dP In this equation ef represents the thermal energy generated due to the irreversibility of the dP system. Substituting dh = q + ef + into the differential energy balance, Eq. (5.3-6), gives dP + gdz + VdV + ef = w This equation can be integrated along a streamline from the inlet to the outlet of the system to give Po Pi where ef = e f dP + g(zo zi) + ,w= 1 (oVo2 iVi2) + ef + w = 0 2 (5.3-9) w , and = kinetic energy correction factor, = 2 for laminar flow, = 1 for turbulent flow. The kinetic correction factor is due to the fact that the velocity profile is not uniform over the cross-sectional area of flow. For uniform flow, the rate of kinetic energy entering a C.V. is given as 1 E k = V 2 VA 2 The kinetic energy per unit mass flow rate is then 5-13 1 E k = V2 VA 2 For turbulent flow, the velocity profile is almost flat, therefore 1 E k V2 = 1 for turbulent flow VA turbulent 2 Uniform velocity profile vz V Laminar velocity profile Figure 5.3-1 Laminar velocity profile in a pipe. The velocity for laminar flow in a pipe is given as r 2 r vz = 2V 1 = 2V (1 2), where = R R The rate of kinetic energy entering a C.V. is E k = Therefore R 0 1 2 v z 2rdr 2 R R r r E k = v z3 rdr = R2 v z3 d 0 0 R R 1 1 E k = R2 8 V3(1 2)3d = 8R2V3 (1 2 ) 3 d 0 0 1 E k = 8R2V3 8 = R2V3 = A V3 Therefore E k 2 = V2, and = 2 for laminar flow VA la min ar 2 5-14