Research plan

advertisement

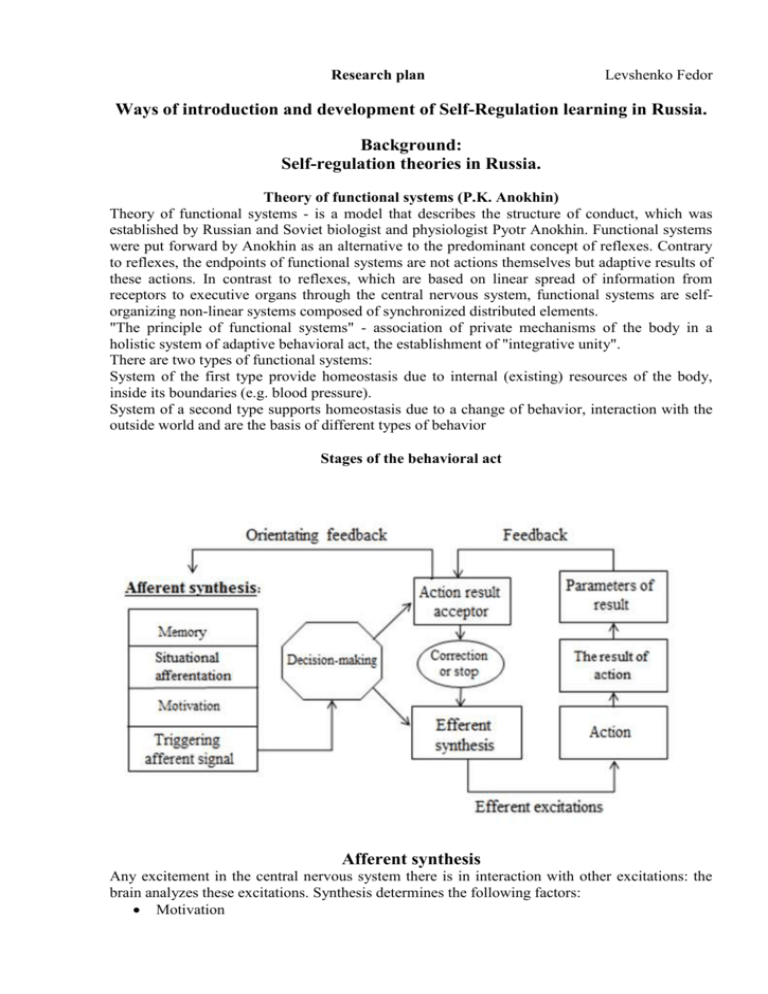

Research plan Levshenko Fedor Ways of introduction and development of Self-Regulation learning in Russia. Background: Self-regulation theories in Russia. Theory of functional systems (P.K. Anokhin) Theory of functional systems - is a model that describes the structure of conduct, which was established by Russian and Soviet biologist and physiologist Pyotr Anokhin. Functional systems were put forward by Anokhin as an alternative to the predominant concept of reflexes. Contrary to reflexes, the endpoints of functional systems are not actions themselves but adaptive results of these actions. In contrast to reflexes, which are based on linear spread of information from receptors to executive organs through the central nervous system, functional systems are selforganizing non-linear systems composed of synchronized distributed elements. "The principle of functional systems" - association of private mechanisms of the body in a holistic system of adaptive behavioral act, the establishment of "integrative unity". There are two types of functional systems: System of the first type provide homeostasis due to internal (existing) resources of the body, inside its boundaries (e.g. blood pressure). System of a second type supports homeostasis due to a change of behavior, interaction with the outside world and are the basis of different types of behavior Stages of the behavioral act Afferent synthesis Any excitement in the central nervous system there is in interaction with other excitations: the brain analyzes these excitations. Synthesis determines the following factors: Motivation Pad afferentation (excitation caused by conditioned and unconditioned stimuli) Situational afferentation (arousal from familiar surroundings, causing a reflex, and dynamic stereotypes) Memory (of species and individual) Decision-making The formation of action result acceptor (creating the ideal image and its retention goals, presumably, at the physiological level is circulating in the ring interneuron excitation) Efferent synthesis (or the stage of the program, integration of somatic and autonomic excitations in a single behavioral act. The action is formed, but is not manifested externally) Action (program execution behavior) Evaluation result of the action At this stage, comparison of the actual running of the ideal image created during the formation of acceptor result of the action (the reverse occurs afferentation) based on a comparison of the action, or adjusted, or terminated. Meeting the needs (authorizing termination of stage) Choice of targets and methods of achieving them are the key factors that regulate behavior. According to Anokhin, in the structure of the behavioral act afferent feedback compared with the acceptor of the result gives a positive or negative situational emotions affect the correction or termination of action (another type of emotion, leading emotions, are associated with satisfaction or dissatisfaction needs in general, with the formation of the target). In addition, the behavior affect the memories of positive and negative emotions. Theory of movement behavior (N.A. Bernstein) The origins of activity theory can be traced to several sources, which have subsequently given rise to various complementary and intertwined strands of development. This account will focus on three of the most important of these strands. The first is associated with the Moscow Institute of Psychology and in particular the "troika" of young Russian researchers, Vygotsky, Leont'ev and Luria. Vygotsky founded cultural-historical psychology, a field that became the basis for modern AT; Leont’ev, one of the principal founders of activity theory, both developed and reacted against Vygotsky's work. Leont'ev's formulation of general activity theory is currently the most influential in post-Soviet developments in AT, which have largely been in socialscientific, organizational, and writing-studies rather than psychological research. The second major line of development within activity theory involves Russian scientists, such as P. K. Anokhin and N. A. Bernshtein, more directly concerned with the neurophysiological basis of activity; its foundation is associated with the Soviet philosopher of psychology S. L. Rubinshtein. This work was subsequently developed by researchers such as Pushkin, Zinchenko & Gordeeva, Ponomarenko, Zarakovsky and others, and is currently most well-known through the work on systemic-structural activity theory being carried out by Bedny and his associates Finally, in the Western world, discussions and use of AT are primarily framed within the Scandinavian activity theory strand, developed by Yrjö Engeström. A systemic-structural theory and Concept of operative image (D.A. Oshanin) After Vygotsky's early death, Leont'ev became the leader of the research group nowadays known as the Kharkov school of psychology and extended Vygotsky's research framework in significantly new ways. Leont'ev first examined the psychology of animals, looking at the different degrees to which animals can be said to have mental processes. He concluded that Pavlov's reflexionism was not a sufficient explanation of animal behaviour and that animals have an active relation to reality, which he called "activity." In particular, the behaviour of higher primates such as chimpanzees could only be explained by the ape's formation of multi-phase plans using tools. Leont'ev then progressed to humans and pointed out that people engage in "actions" that do not in themselves satisfy a need, but contribute towards the eventual satisfaction of a need. Often, these actions only make sense in a social context of a shared work activity. This led him to a distinction between "activities," which satisfy a need, and the "actions" that constitute the activities. Leont'ev also argued that the activity in which a person is involved is reflected in their mental activity, that is (as he puts it) material reality is "presented" to consciousness, but only in its vital meaning or significance. AT remained virtually unknown outside the Soviet Union until the mid-1980s, when it was picked up by Scandinavian researchers. The first international conference on activity theory was not held until 1986. The earliest non-Soviet paper cited by Nardi is a 1987 paper by Yrjö Engeström: "Learning by expanding". This resulted in a reformulation of AT. Kuutti notes that the term "activity theory" "can be used in two senses: referring to the original Soviet tradition or referring to the international, multi-voiced community applying the original ideas and developing them further." The Scandinaviant AT school of thought seeks to integrate and develop concepts from Vygotsky's Cultural-Historical Psychology and Leont'ev's activity theory with Western intellectual developments such as Cognitive Science, American Pragmatism, Constructivism, and Actor-Network Theory. It is known as Scandinavian activity theory. Work in the systemsstructural theory of activity is also being carried on by researchers in the US and UK. Some of the changes are a systematisation of Leont'ev's work. Although Leont'ev's exposition is clear and well structured, it is not as well-structured as the formulation by Yrjö Engeström. Kaptelinin remarks that Engeström "proposed a scheme of activity different from that by Leont'ev; it contains three interacting entities—the individual, the object and the community— instead of the two components—the individual and the object—in Leont'ev's original scheme." Some changes were introduced, apparently by importing notions from Human-Computer Interaction theory. For instance, the notion of rules, which is not found in Leont'ev, was introduced. Theory of conscious self-regulation of behavior (O.A. Konopkin, V.I. Morosanova) Theoretical framework: Self-Regulation learning Self-regulated learning (SRL) theories attempt to model how each of these cognitive, motivational, and contextual factors influences the learning process (Pintrich, 2000; Winne, 2001; Winne & Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000). Although there are important differences between various theoretical definitions, self-regulated learners are generally characterized as active, efficiently managing their own learning through monitoring and strategy use (Boekaerts, Pintrich, & Zeidner, 2000; Butler & Winne, 1995; Paris & Paris, 2001; Pintrich, 2000; Winne, 2001; Winne & Hadwin, 1998; Winne & Perry, 2000; Zimmerman, 2001). Students are self-regulated to the degree that they are metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their learning (Zimmerman, 1989). SRL has also been described as a constructive process wherein learners set goals on the basis of both their past experiences and their current environments (Pintrich, 2000). These goals become the criteria toward which regulation aims. In essence, SRL mediates the relations between learner characteristics, context, and performance (Pintrich, 2000, 2004). Regulation Of Motivation As A Component Of Self-Regulated Learning Many models of self-regulated learning also presume that students manage aspects of the learning process in addition to their actual cognitive processing. Students’ ability to control aspects of their motivation, more specifically, is thought to have an impact on their learning and achievement. Research examining self-regulation from a volitional perspective, for example, has emphasized students’ efforts to increase their persistence or time on task (Corno, 1993, 2001; Kuhl, 1985). Motivation has also been identified as one area of the learning process that students actively selfregulate within social cognitive models of self-regulated learning (Zimmerman, 1994). To define regulation of motivation, the meaning of achievement motivation itself needs to be clarified. Behaviorally, theories of motivation attempt to explain outcomes such as students’ choice of activities, the intensity of their effort or level of cognitive engagement within those activities, and their persistence at those activities (Graham&Weiner, 1996; Pintrich & Schrauben, 1992; Winne & Marx, 1989). Historically, efforts to understand and explain these behavioral outcomes have relied on factors that include instincts, internal drives or traits, behavioral associations, and psychoanalytic forces (Graham & Weiner, 1996; Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). In contrast, more contemporary models of motivation emphasize the importance of cognitive constructs such as students’ causal attributions, perceptions of self-competence, value, interest, feelings of self-determination, and reasons for engaging in an activity (Graham&Weiner, 1996; Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). Winne and Hadwin’s Model of SRL There are numerous theories of SRL that differ in sometimes subtle and sometimes significant ways (for extensive reviews, see Boekaerts et al., 2000; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001). Winne and Hadwin (1998) posited that learning occurs in four basic phases1: task definition, goal setting and planning, studying tactics, and adaptations to metacognition (see Figure 1). The first notable difference between Winne and Hadwin’s model and that of Pintrich (2000) is that they separated the processes of task definition from those of goal setting and planning. In addition, Winne and Hadwin’s (1998) SRL model differs from others in that they hypothesized that an IPT-influenced set of processes occurs within each phase. Using the acronym COPES, they described each of the four phases in terms of the interaction of a person’s conditions, operations, products, evaluations, and standards. All of these aspects, except operations, are kinds of information that a person uses or generates during learning. It is within this cognitive architecture, composed of COPES, that the work of each phase is completed. Thus, Winne and Hadwin’s model complements other SRL models by introducing a more complex description of the processes underlying each phase. FIGURE 1. Winne and Hadwin’s (1998) model of self-regulated learning. Source. Winne, P. H. (2001). Self-regulated learning viewed from models of information processing (p. 164). Aims and objectives This theoretical review provides evidence to support scientific claims. First, current research and theory are examined from the perspective afforded by using SRL-model in Russia. I believe that the cognitive architecture and focus on monitoring that differentiate SRL model align with much in current research while providing additional explanatory power and excellent results in new area. Self-regulation learning model describes the specific cognitive processes that entail a learner’s self-regulation through the definition of a task, the setting of goals and plans, the use of tactics to learn, and the metacognitive processes used to adapt learning both within the task and more globally. The purpose of this research is to evaluate the theoretical concerning regulation of motivation to emphasize its importance to students’ self-regulated learning in Russia. To achieve this goal the theoretical background is divided into tree sections. In the first section, a working definition of self-regulation learning is provided. In the second section, the theoretical distinctions between regulation of motivation and SRL are evaluated. In the third section, this conceptual understanding is used to identify and describe a number of strategies that might be useful to implement SRL within academic contexts. It is important to note that this is a theoretical research, not a comprehensive review of empirical literature in any one particular topic area. SRL models, including Winne and Hadwin’s, generally cover a broad array of phenomena, including many well-researched areas, such as goal setting, motivation, personal epistemology, and emotions. It would be a formidable and lengthy task indeed to review the theoretical work in each area. As part of this discussion, these strategies to students’ choice, effort, cognitive engagement, or academic performance is reviewed. I believe that implementing this model in Russia makes unique and important contributions to understanding SRL. This allows the model to explicitly detail the recursive nature of SRL. Finally, this model separates out task definition and goal setting into separate phases, allowing more nuanced questions to be asked about these phenomena. SRL model (as outlined by Pintrich, 2000) suggest new ways of conceptualizing and analyzing the learning process. In addition, I believe that these contributions also point to profitable new directions for future research. Research methods Theoretical research is formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge, within the limits of the critical bounding assumptions. The theoretical analyze makes the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical issues are introduces and describes the theory which explains why the research problem under study exists. Research framework consists of concepts, together with their definitions, and existing theory/theories that are used for particular study. This thesis will demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of research paper and that will relate it to the broader fields of knowledge in the class you are taking. This research is something that is found readily available in the literature. I will review course readings and pertinent research literature for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power. Observational research. There are many types of studies which could be defined as observational research including case studies, ethnographic studies, ethological studies, etc. The primary characteristic of each of these types of studies is that phenomena are being observed and recorded. Often times, the studies are qualitative in nature. A detailed report with analysis would be written and reported constituting the study of this individual case. These studies may also be qualitative in nature or include qualitative components in the research. Literature Review Although this review addresses each aspect of SRL model, it is important to remember the recursive nature of the model within individual phases, across phases, and from external feedback. For each aspect, beginning with the determination of task conditions, the relevant research is examined, along with general comments about what the model contributes to research in that area, including possible new directions. I am going to present comprehensive reviews of research from every subsection. I present only research that aids in main goals of illustrating the benefits of using SRL research through the lens of Time table 1. Examine future thesis title and research problem. The research problem anchors study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework. Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin future study. This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline. 2. Brainstorm on what you consider to be the key variables in your research. Answer the question, what factors contribute to the presumed effect? Position of theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories. There will likely be several concepts, theories, or models of SRL that can be used to help develop understanding the research problem. 3. Review related literature to find answers to your research question. Review the key SRL science theories that are introduced to you in many course readings and choose the theory or theories that can best explain the relationships between the key concepts. 4. Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research. The present tense is used when writing about theory. I will make theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible. Later, in discussion part I should link it back to theoretical framework. Expected results and possible risks This theoretical research has strengthens the study in the following ways: 1. Statement in theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically. 2. The new theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, those are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods. 3. Articulating assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to move from simply describing a phenomenon observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon. 4. Having a theory helps to identify the limits of using SRL in Russia. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a SRL of interest. It alerts you to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances. By virtue of its application nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges of a SRL phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways. Ethical issues Given the importance of ethics for the conduct of research, it should come as no surprise that many different professional associations, government agencies, and universities have adopted specific codes, rules, and policies relating to research ethics. The following is a rough and general summary of some ethical principals that various codes address: Honesty Strive for honesty in all scientific communications. Honestly report data, results, methods and procedures, and publication status. Do not fabricate, falsify, or misrepresent data. Do not deceive colleagues, granting agencies, or the public. Objectivity Strive to avoid bias in experimental design, data analysis, data interpretation, peer review, personnel decisions, grant writing, expert testimony, and other aspects of research where objectivity is expected or required. Avoid or minimize bias or self-deception. Disclose personal or financial interests that may affect research. Integrity Keep your promises and agreements; act with sincerity; strive for consistency of thought and action. Carefulness Avoid careless errors and negligence; carefully and critically examine your own work and the work of your peers. Keep good records of research activities, such as data collection, research design, and correspondence with agencies or journals. Openness Share data, results, ideas, tools, resources. Be open to criticism and new ideas. Respect for Intellectual Property Honor patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. Do not use unpublished data, methods, or results without permission. Give credit where credit is due. Give proper acknowledgement or credit for all contributions to research. Never plagiarize. Confidentiality Protect confidential communications, such as papers or grants submitted for publication, personnel records, trade or military secrets, and patient records. Responsible Publication Publish in order to advance research and scholarship, not to advance just your own career. Avoid wasteful and duplicative publication. Respect for colleagues Respect your colleagues and treat them fairly. Social Responsibility Strive to promote social good and prevent or mitigate social harms through research, public education, and advocacy. Non-Discrimination Avoid discrimination against colleagues or students on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, or other factors that are not related to their scientific competence and integrity. Competence Maintain and improve your own professional competence and expertise through lifelong education and learning; take steps to promote competence in science as a whole. Legality Know and obey relevant laws and institutional and governmental policies. Human Subjects Protection When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy; take special precautions with vulnerable populations; and strive to distribute the benefits and burdens of research fairly. Literature 1. Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations Gavriel Salomon (1996) Cambridge University Press p. 299 2. How Experts Differ from Novices J D Bransford, A L Brown, R R Cocking (2000) How People Learn Brain Mind Experience and School (2) p. 31-50 3. Institutional culture, social interaction and learning Harry Daniels (2012) Learning Culture and Social Interaction 1 (1) p. 2-11 4. Key Design Considerations for Personalized Learning on the Web Margaret Martinez, D Ph (2001) Educational Technology & Society 4 (1) p. 26-40 5. Motivation and the ecology of collaborative learning C K Crook (2000) Rethinking collaborative learning p. 161-178 6. Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction Mark L Knapp, Judith A Hall (2009) Wadsworth, Cengage Learning 5 p. 496 7. Pattern discovery for the design of face-to-face computer-supported collaborative learning activities Maria Francisca Capponi, Miguel Nussbaum, Guillermo Marshall, Maria Ester (2010) Educational Technology & Society 13 (2) p. 40-52 8. Personalized e-learning through environment design and collaborative activities Felix Mödritscher, Fridolin Wild (2008) Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the Workgroup HumanComputer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society on HCI and Usability for Education and Work LNCS 5298 5298/2008 (Cmi) p. 377-390 Social Psychology , Sociological 9. Evolutionary Social Psychology, Social Experiments, Small-group Interaction, Social Psycho, Social Psy (2001) International Encyclopedia of Social Behavioral Sciences 27 (11) p. 14409-14413 10. Sociological Theory and Social Control Morris Janowitz (1975) American Journal of Sociology 81 (1) p. 82-108 11. The social being in social psychology. Shelley E Taylor (1998) Handbook of social psychology 1 p. 58-95 12. The validity of collaborative assessment for learning Eleanore Hargreaves (2007) Assessment in Education. Principles, Policy & Practice 14 (2) p. 185-199 13. A method for improving paired collaborative learning through approaches of computational intelligence K Shin-ike, H Iima (2009) 14. Collaborative and Cooperative Learning J M McInnerney, T S Roberts (2005) Encyclopedia of Distance Learning 1999 p. 269-276