Session 11. GDP statistics by activity

advertisement

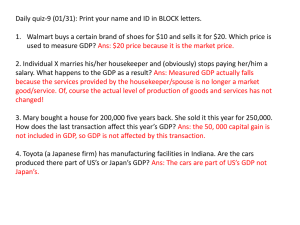

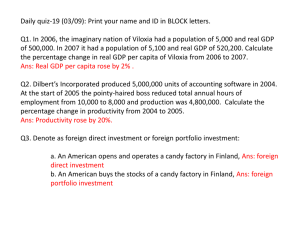

Module H5 Session 11 Session 11. GDP statistics by activity Learning objectives At the end of this session the students will be able to distinguish clearly between current and constant prices calculate the share of an industrial sector in the GDP calculate growth rates from the constant price data calculate the implied deflators understand the main differences between the CPI and the GDP deflator GDP at current and at constant prices After two sessions of SNA theory, we turn our attention to the GDP and its components. Look at the tables on the next page. They show the GDP of South Africa presented according to the production approach and showing the gross value added of each industry. The first table shows the figures at current prices and the second table shows the figures at constant (2000) prices. The base year is the year 2000. GDP at current prices GDP at current prices refers to the value of GDP measured (in theory) according to the value of each transaction at the time it takes place. The definition of the gross value added of each industry is its total output minus its intermediate consumption (see Session 9). GDP at constant prices In line with index number theory, changes in the values of goods and services can be split between changes in the prices of the goods and services and changes in their “volumes”. GDP at constant prices is a measure of the volume of production taking place in the country. It is GDP at current prices with the inflation taken out. Conceptually, all transactions are measured as if they had taken place at the average prices of the base year. In the base year the figures at current and at constant prices are identical. In principle, according to the production approach, GDP is the volume of outputs minus the volume of inputs, combined using base year prices. GDP can also be calculated at constant prices according to the expenditure approach, by deducting imports measured at constant prices from the sum of the other components measured at constant prices. In theory the result is identical. SADC Course in Statistics Module H5 Session 11 – Page 1 Module H5 Session 11 South Africa: GDP by industry at current prices (million Rand) 2000 Agriculture, forestry and fishing Mining and quarrying Manufacturing Electricity, gas and water Construction Wholesale and retail trade; hotels and restaurants Transport, storage and communication Finance, real estate and business services General government services Personal services Total value added at basic prices Taxes less subsidies on products GDP at market prices 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 27,451 63,391 159,107 22,789 21,114 122,702 32,588 77,214 176,907 23,023 22,416 130,387 44,179 92,113 209,605 26,046 24,119 143,095 40,889 84,258 221,652 28,316 26,947 157,728 39,432 89,290 237,100 29,645 29,838 175,738 37,625 100,515 254,993 31,574 33,161 191,549 41,632 120,221 278,794 33,579 39,414 213,233 80,872 89,511 100,034 110,439 122,240 131,955 145,044 156,252 177,531 204,667 229,007 260,151 293,481 337,301 133,158 142,325 157,312 174,548 193,423 209,471 226,458 51,382 56,313 62,631 69,895 76,998 84,055 94,327 838,218 928,216 1,063,801 1,143,679 1,253,854 1,368,378 1,530,002 83,930 91,792 104,898 117,014 144,305 170,590 197,476 922,148 1,020,008 1,168,699 1,260,693 1,398,159 1,538,968 1,727,478 South Africa: GDP by industry at constant 2000 prices (million Rand) 2000 Agriculture, forestry and fishing Mining and quarrying Manufacturing Electricity, gas and water Construction Wholesale and retail trade; hotels and restaurants Transport, storage and communication Finance, real estate and business services General government services Personal services Total value added at basic prices Taxes less subsidies on products GDP at market prices 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 27,451 63,391 159,107 22,789 21,114 26,558 63,325 164,131 21,956 22,154 28,292 63,927 168,729 22,722 23,441 27,700 66,502 166,405 23,151 25,053 28,083 67,363 174,197 23,835 27,830 29,232 68,987 182,917 24,460 31,134 25,390 68,536 191,630 25,207 35,401 122,702 125,018 127,870 136,138 144,111 153,497 163,754 80,872 85,646 93,390 98,864 103,500 109,165 115,088 156,252 169,015 179,623 187,062 201,756 212,885 230,402 133,158 51,382 838,218 83,930 922,148 131,914 52,537 862,254 85,120 947,374 132,859 136,018 139,349 144,166 148,589 53,852 56,074 57,183 60,241 62,442 894,706 922,966 967,208 1,016,684 1,066,438 87,416 89,797 94,563 99,133 104,928 982,122 1,012,763 1,061,771 1,115,817 1,171,366 Source: Statistics South Africa Technical note: Theoretically, for measuring changes in the volume of production, the SNA prefers the use of chained (Fisher) indices, but it recognises that the traditional Laspeyres approach using a fixed base year (updated from time to time) is more practical and most countries continue to use it. An important advantage of the latter is that the components add up to the totals, which is not the case for other types of indices. SADC Course in Statistics Module H5 Session 11 – Page 2 Module H5 Session 11 Derived GDP statistics Several types of statistics can be derived from the estimates of GDP. Shares of (or percentage contributions to) GDP When comparing any monetary value to the GDP, GDP at current market prices should be used as the denominator (on the bottom). Each industry contributes to the GDP. Put another way, each industry has a share of the GDP. The share and the contribution are the same, and can be expressed as a percentage. To calculate the percentage contribution (or share) of agriculture, divide the gross value added (GVA) of agriculture by the GDP at market prices and multiply by 100. The calculation should be done using the figures at current prices. (If you were to use the constant price figures for GVA and GDP you will get slightly different answers, depending on the base year. The meaning of these different figures is not obvious, and to avoid confusion the current price figures should be used.) Growth rates The usual headline statistic is the “growth rate” of GDP at constant prices. This is the percentage change in the volume of production in a given year compared with the previous year. The standard way to calculate this change is to divide the figure for the year in question by the figure for the year before, subtract one, and express the result as a percentage. The growth rates may be calculated for each industry. The annual growth rates can be quite volatile, especially if agriculture contributes significantly to the GDP and if it is affected by the weather. See the box on the next page. Index numbers The GDP and its components at constant prices can also be expressed as (quantity) index numbers. This makes it easier to see how the various components have moved especially in relation to the base year. These index numbers are calculated by dividing the figures in each row by the figure in the base year and multiplying by 100. Implied deflators “Implied deflators” are obtained by dividing the figures at current prices by the corresponding figures at constant prices and multiplying by 100. The results of this operation are price indices, indicating the effects of inflation on the value added in each industrial sector or component. Literally, a “deflator” is a price index used to convert estimates at current prices into estimates at constant prices. However these deflators are “implied” (or “implicit”) because they have not actually been used in this way. The constant price estimates will have been compiled in various ways and in greater detail; the implied deflators are calculated results, and not themselves used to calculate anything. SADC Course in Statistics Module H5 Session 11 – Page 3 Module H5 Session 11 Exercise 1 Based on the estimates of GDP from South Africa and using Excel, make tables showing the following statistics the share of each industry in the GDP at (current) market prices divide each current price figure by the corresponding GDP the growth rates (at constant prices) for each activity divide each constant price figure by the figure in the previous year and subtract 1. index numbers of the volumes of production divide each constant price figure by the base year figure and multiply by 100 the implied deflators divide the current price figures by the corresponding constant price figures and multiply by 100. Describe in words the main features of the South African economy in 2006, compared with 2005. (Alternatively, you could do the same using the equivalent tables for your country.) The GDP deflator and the CPI The (implied) GDP deflator is often seen by users as an alternative measure of inflation to the Consumer Price Index. What is the difference? Usually one would expect the two measures to show more or less the same movements on an annual basis. But there may be differences, sometimes quite large. There are several possible reasons for the differences as follows: The CPI measures the change in prices experienced by an average household. The GDP deflator measures the change in prices in domestic production. In principle, the latter excludes the direct effect of any change in the price of imports, but includes changes in the price of exports. The sources of price data may be different, the weighting is certainly different. In theory, the CPI is closer to the national accounts deflator for final household consumption expenditure, but the coverage may not be the same (the CPI may cover only urban populations, for example, or exclude own-account consumption). In some countries, the CPI may be used directly to deflate current price estimates of final household consumption expenditure. The CPI is a Laspeyres index. The implied GDP deflators are Paasche indices. SADC Course in Statistics Module H5 Session 11 – Page 4 Module H5 Session 11 Discussion topic Interpreting growth rates Suppose you were offered a choice of salary increase. You can have either (a) a nine per cent increase this year, followed by a three per cent increase next year, or (b) three per cent this year and a further nine per cent next year. Which would you choose? I would choose option (a) because it would give me more in total. I would prefer 9% followed by 3% rather than 3% followed by 9%. But suppose GDP rose by 9% one year and by 3% the next. It is curious that most commentators would consider this to be bad news, a “slow down” in the rate of growth. On the other hand if GDP rose by 3% and then by 9% it would be considered good. In both cases the new level of GDP would be a bit ore than 12% higher than before It all depends on the extent to which you consider changes in the rate of growth to represent a trend or not. That depends on how much random variation there is in the growth rates. In a relatively small economy, random variation is much more likely than steady growth. A 9 per cent increase in one year does not make it likely that the growth rate will be even higher the following year. Any further large increase over an exceptional 9 per cent would be remarkable. Growth rates in each sector are likely to be much more variable than that of the total (see the case of South Africa). And the growth rates of individual businesses may vary even more, especially when starting up. Once a business has reached its capacity it may not grow much further at all, but continuing in business may be sufficient for the owner to be satisfied. A large new business in a previously small sector can make the growth rate very high for a short period, but a similar increase thereafter is only likely if other new businesses start up. Conclusion: a 3% increase on top of a 9% increase in a sector is not a fall, and should not be seen as a disaster. Graphs should show the levels, not the growth rates, especially if the latter are volatile. SADC Course in Statistics Module H5 Session 11 – Page 5