Nationwide Dentist and Executive Director Survey of Community

advertisement

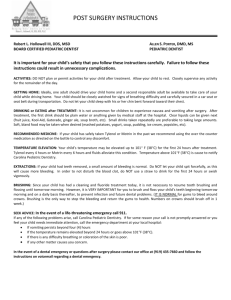

Nationwide Dentist and Executive Director Surveys of Community Health Center Retention and Recruitment Issues, Work Environment Perceptions, and Salaries Introduction Access to dental care is still a challenge for millions of the underserved (1, 2). A major factor contributing to the problem is the difficulty in recruiting and retaining dentists to provide that care. For many years, the federal government has taken steps to make dental care more available to low-income people. The primary vehicle for this has been Medicaid, a joint federal and state health financing program for more than 40 million people from low- income families and poor aged, blind, or disabled people. The State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) covers about 2 million additional lowincome children who do not qualify for Medicaid. Still other programs support community and migrant health centers and other facilities and medical personnel in locations where low-income people live. These programs, although relatively small compared with Medicaid, extend health care services to many additional low-income and vulnerable populations. The four major federal programs other than Medicaid and SCHIP that target services or providers to underserved or special populations with poor dental health: 1) the Health Center program (Public Health Service 330 grant funding), 2) the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), 3) the Indian Health Service (IHS) dental program, and 4) IHS loan repayment program--currently have a limited effect on increasing the access to dental services that low-income and vulnerable populations have. The Health Center program supports community and migrant health centers in medically underserved areas, while the IHS loan repayment program provides incentives for health professionals, including dentists, to practice in sites serving American Indians and Alaska Natives. However, these programs are not able to meet the dental needs of their target populations. NHSC was able to fill only one of every three vacant dentist positions in underserved areas in fiscal year 1999 (2). Governmental incentives such as the scholarship program and loan repayment program operated by the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) have not been completely successful. Too few health care professionals participate, retention rates are low, and underfunding of programs consistently occurs (2,3). Anecdotal reports of numerous vacancies for dentists in Community, Migrant, and Homeless Health Centers (CHCs) persist and reasons for difficulty in recruiting and retaining dentists continue to be topics of intense speculation. However, few published studies exist which attempt to analyze the reasons for such problems, or even if the problem of recruitment and retention of dentists in CHCs is prevalent enough to warrant concern. This study attempts to answer some of these questions and quantify the magnitude of these issues. The aims of this study are: 1) to identify characteristics of dentists who currently serve in CHCs, 2) determine the proportion of dentists that intend to remain in CHCs for the remainder of their careers, and 3) explore associations of factors which may affect the 1 retention of existing dental providers. Executive directors of CHCs with dental components were queried for exact figures dealing with numbers and duration of vacancies for dentists and dollar amounts of compensation ranges for existing practitioners as well as for potential recruits. Methods Survey Instruments and Implementation. Two separate survey instruments were used (Appendices 1, 2). The survey instruments were addressed to all dentists employed by CHCs and executive directors of CHCs with dental components. Questionnaires were designed for the two groups based on input from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Regional Dental Consultants, Dental Directors from key Community, Migrant, and Homeless Health Centers, the author, and other interested parties. The dentist survey consisted of 26 questions dealing with years of experience, advanced general dentistry education, practice experience prior to working in the CHC, current position in the CHC, current compensation and perquisites, perceptions of work environment, and other general job satisfaction determinants. Finally, the dentists were asked if they planned to remain in their CHC position and, if not, how soon they planned to leave. The executive director survey asked 19 questions relating to the number of dentists employed, number and duration of vacancies existing, methods currently being used to recruit for vacancies, numbers of applicants for vacant positions, reasons for applicants rejecting firm offers for employment, compensation currently being paid to existing dental providers, and budgeted compensation for new positions ranging from entry level dentist with no experience to experienced level dentist (10 years or more). Both questionnaires offered total anonymity and were approved by the Baylor College of Dentistry institutional review board. Addresses of dentists were obtained from HRSA Regional Dental Consultants or their counterparts in the ten HRSA regions. Executive Director addresses were obtained from the most recent available roster of Public Health Service 330 grantees. An attempt to query every CHC which had at least one dentist employed and all executive directors of CHCs with dental components was made. To the extent of the accuracy and completeness of the provided names and addresses, the anonymity of the survey, and the incomplete ability to track responses based on ZIP codes on the postmarked returned envelopes, it is not known if this goal was indeed accomplished. A total of 569 mailings were made to dentists and 345 mailings to executive directors in February and March of 2002. A selfaddressed postage paid envelope was enclosed with each mailing. Response rates were 73.8% from the dentist mailings (420/569) and 46.1% from the executive director mailings (159/345). Analysis Data from the responses to both survey instruments were entered on Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and transferred to SPSS PC version 11 for analysis. For each question answered on the survey a frequency analysis was performed. To measure associations 2 between variables, various statistical tests were performed as indicated. Contingency table analysis was performed to obtain chi-square values and, where the assumptions for the chi-square test were not met, Fisher’s exact test was used. T-tests were used to compare between-group means for continuous variables. Bivariate logistic regressions were performed on six selected variables with “intention to leave community health care dentistry” as the dependent variable. Variables were categorical with the exception of salary, which was a continuous variable. The seven independent variables were 1) salary, 2) position (dental director, staff dentist) 3) years of dental practice, 4) freedom to exercise professional judgment in the treatment of patients, 5) altruistic motivation, 6) high value placed on loan repayment, and 7) amount of administrative time available for those dentists with administrative duties. Variables which met a significance level of p<.05 in each bivariate analysis were placed in a multivariate logistic regression model to measure extent of these associations, with the exception of variable number 7, which did not apply to the entire group, but to a subset: dental directors. Results Dentist Survey Of the 569 surveys mailed to dentists, responses from 420 dentists were received; a response rate of 73.8 percent. The mean years since graduation from dental school was 15.0±11.2 with a median of 12 years. The mean number of years worked in a CHC was 7.1±6.9 with a median of 4.5 years. The majority of respondents (56%) had >10 years of dental practice experience, 20.2% had between 5 and 10 years, 17.3% between 1 and 5 years, and 6.5% had <1 year of practice experience. The single predominant activity prior to employment in a CHC was private practice associate or employee (33.5%). Percentages of responses in six categories of prior activity are listed in Table 1. TABLE 1 Activity Prior to CHC Employment (N=409) N Percent Private practice/Associate or employee 137 33.5 Dental Student 105 25.7 Private practice/Owner or partner 86 21.0 Graduate program/Specialty program 40 9.8 Commissioned Officer in military or PHS 39 9.5 Retired 2 0.5 Dentists were asked to rank reasons they chose to work in a community health care organization. The three most prevalent responses were: 1) “felt a mission to the dentally underserved population” (72.7%), 2) “wished to practice dentistry in a community based setting” (66.5%), and 3) “attracted by the work schedules and leave policies of Community Health Center” (58.6%). The least selected reason for choosing Community Health Care was “sold private practice, or retired from government service” (15.1%). Totals are more than 100% due to multiple possible responses. 3 Respondents classified themselves as staff dentist 53.6% and as dental director 45.2%. The majority (93.6%) categorized themselves as general dentists. Of the 383 general dentists, 27.4% had advanced training in general dentistry: 19.5% completed GPR programs and 7.9% had completed AEGD training. The remaining 72.6% had no advanced training in general dentistry. Other specialties reported were pediatric dentistry (1.7%) and dental public health (4.6%). When dentists were asked if they perceived complete freedom to exercise their professional judgment in treating patients in a CHC environment, 65.7% answered that they were completely free to do so, while 34% did not feel completely free. In the areas of work environment and perceptions of working conditions, dentists responded in a generally positive way. Perception of facility quality, including building, equipment, and supplies was good or very good in 66.7% of responses (275/412). Less than 2% considered the quality as poor. On-call weekend and evening duties were reported as occurring either seldom or never by 76.2% of the respondents (311/408). Less than 3% felt the on-call duties were excessive. Continuing education allowances were offered to 89.0% of employed dentists with a median number of 5 days and a median of $1500 reimbursement reported. The mean number of days offered for vacation was 17.9 ± 5.9 with a median of 20 and 81.5% of respondents felt this was an adequate amount. For those dentists with administrative duties (N=208), only 28.8% felt they were allowed enough time for those duties. A total of 71.1% felt that there was either not enough time, or no administrative time was allowed in their schedules. The next lowest frequent positive response was for production incentive plans--only 29.4% of dentists reported the availability of such plans. Other indicators and perceptions are displayed in Table 2. Self-reported salaries for dental directors and staff dentists are shown in Table 3. Further salary breakdown by region and by position are given in Appendix 3. TABLE 2 Indicators Receiving “Yes” Responses from Dentists Continuing Education Allowance Salary Incentive Plan Offered 403b or Similar Plan Offered Adequate Insurance Coverage Adequate Amount of Leave Time Adequate Number of Dental Assistants Adequate Quality of Dental Assistants Adequate Clerical Support Adequate Administrative Support Adequate Administrative Time Allowed 4 N 356/400 116/395 324/389 302/380 312/383 285/408 Percent 89.0 29.4 83.3 79.5 81.5 69.9 349/404 267/399 300/391 60/208 86.4 66.9 76.7 28.8 TABLE 3 Dentist Self-Reported Pre-Tax Salary Annualized (N=357) Mean Median Minimum Maximum Std. Deviation Staff Dentist (N=178) 81,603 80,000 30,000 200,000 23,775 Dental Director (N=179) 91,653 90,000 39,000 210,000 23,038 Finally, the dentist survey asked “Do you intend to remain in Community Health Center based dentistry?” Respondents were asked to answer yes or no to this question. Dentists answering in the negative were given a follow-up question asking how soon the dentist planned to leave their current position in the CHC. Over two-thirds (68.8%) of the respondents indicated an intention of remaining in CHC dentistry (278/404). The remaining 31.2% indicated they did not intend to remain in Community Health Dentistry (126/404). Of those indicating this intention, 12.7% intended to leave as soon as another opportunity opened. Thirty percent intended to leave within the next year and 41.3% within two to five years. Those planning to leave due to retirement numbered 16%. Chi-square tests were used to compare the reported salaries of staff dentists and dental directors who intended to leave community health dentistry versus those who did not. Neither current position in the dental center (staff dentist or dental director) nor salary was significantly associated with intention to leave (p>.05). But, length of time in service in CHC dentistry significantly affected retention of existing providers. Of the 68.8% of respondents who indicated an intention to remain in CHC dentistry, the mean number of years of practice in a community health care setting was 8.29, while the 31.2% who planned to leave community health care had a mean of only 4.69 years of CHC employment. An independent samples t-test showed that this finding was highly significant (p<.0001). Bivariate logistic regression verified the significance of the association of the intention to leave community health care dentistry for those dentists with less than one year of practice experience (OR=10.2, p<.0001), with >1 but <5 years of experience (OR=6.9, p<.0001), and with >5 but <10 years of experience (OR=3.4, p<.0001) compared to dentists with more than ten years of experience. Contingency table analyses were performed on several factors which were suspected to affect job satisfaction in CHC dental clinics: Perceptions of 1) degree of professional freedom in treating patients, 2) restrictions involving the degree of availability of specialty referral options, 3) level of cooperation from CHC administration, and 4) level of cooperation from CHC boards of directors. Chi-square tests revealed significant differences in the consideration of whether dentists intended to remain in CHC dentistry vis-à-vis their general perception of the degree of professional freedom allowed them in treating patients (p=.001). More specifically, intent to remain when there was a perception of restriction of professional freedom involving the degree of availability of specialty referral options was also significant (p=.014). A chi-square test adding a layered variable of the dentist’s position was performed. Taking into account the dentist’s 5 position in the CHC , the intent to stay in CHC dentistry, and the perception of level of cooperation from the administration of the CHC, the association was significant for the staff dentists (Fisher’s test p<.0001), and for the dental directors (p=.003). Similarly, adding the layered variable of the dentist’s position to the chi-square test of the intent to stay in CHC dentistry, and the perception of level of cooperation from the CHC board of directors showed a significant association for the staff dentists (Fisher’s test p=.006), and for the dental directors (p=.011). Bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that dentists who did not perceive that they were completely free to exercise their professional judgment in the treatment of their patients for whatever reason were twice as likely to indicate an intention to leave CHC dentistry than those who felt they were completely free to do so (OR= 2.0, p=.002). Other studies have suggested that altruistic motivation is a significant factor in physicians and dentists continuing to care for underserved populations (4,5,6). In this survey, dentists who ranked “felt a mission to the dentally underserved population” as first in their top five reasons for choosing a practice opportunity with a community health care organization were significantly more likely to indicate they were remaining in CHC dentistry as opposed to those dentists who did not highly rank that reason (p=.003) The significance of this association was present in bivariate logistic regression analysis (OR=2.1, p=.004). In sharp contrast, dentists who ranked “loan repayment was offered or promised to you in community health care dentistry” first or second in their top five reasons for choosing CHC dentistry were significantly more likely to indicate they were leaving CHC dentistry than those dentists who did not rank loan repayment highly in their reasons for choosing employment in a CHC setting (p<.0001). Bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that dentists who ranked loan repayment highly in their reasons for choosing employment within a CHC setting were significantly more likely to indicate an intention to leave CHC dentistry than those who did not. (OR= 4.8, p<.0001). Respondents who identified themselves as dental director were asked about their perceptions of the amount of administrative time allowed them in the performance of their duties. A Chi-square test was significant in measuring the association between dental directors who are planning to leave CHC dentistry and the perception of an adequate amount of administrative time allowed (p=.002). Bivariate logistic regression analysis showed that dentists who felt they did not have enough administrative time in the performance of their duties as dental director were significantly more likely to indicate an intention to leave CHC dentistry than those who thought they had enough administrative time. (OR 2.97, p=.005) The results of a multivariate logistic backwards stepwise (conditional) regression model using the four variables significantly associated with intent to leave community health care dentistry in bivariate analyses are listed in Table 4. 6 TABLE 4 Variables Associated with Dentists’ Intent to Leave Community Health Care Dentistry: Results of Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Variable Estimate Log OR 1. Not completely free to 0.784 exercise professional judgment in treating patients 2a. Less than 1 year 2.116 experience when compared to 10 years or more 2b. >1 but < 5 years 1.367 experience when compared with 10 years or more 2c. >5 but < 10 years of 0.693 experience when compared with >10 years 3. Did not rank mission to 0.679 the underserved as first reason to choose community health dentistry 4. Rank loan repayment 1.022 st nd highly (1 or 2 ) in reason to choose community health dentistry Std. Error .257 Odds Ratio 2.190 95% CI of X2 OR 1.325, 3.621 9.340 p .501 8.299 3.106, 22.177 17.806 <.0001 .341 3.924 2.011, 7.656 16.075 <.0001 .326 1.999 1.055, 3.787 4.518 .034 .300 1.972 1.095, 3.553 5.112 .024 .284 2.779 1.592, 4.852 12.923 <.0001 Executive Director Survey The concurrently administered executive director survey was designed to determine the number and duration of existing vacancies within the dental component of the surveyed CHC, as well as current salaries of dentists. Information was requested regarding budgeted salaries as well as current salary and benefits packages being paid to dental directors and dentists. Administrators were asked about methods used to recruit for the vacancy or vacancies, number of applicants responding, number of offers made, and number of offers rejected. Reasons for offers being rejected were also explored. Only fifty-two percent of executive directors responding indicated no current vacancies in the dental component of their CHC (83/159). Out of the 47.8% (76/159) which did have vacancies, the mean number of vacancies was 1.67 ± .99, and the predominant length of the vacancy was less than 6 months (60.5%). The great majority of vacancies was twelve months or less (81.6%). Methods used to recruit for the existing vacancy were varied. The top four methods used were newspaper advertisements (61.3%), 7 .002 postings at dental schools (58.8%), working with the National Health Service Corps (58.8%), and dental journal advertisements (47.5%). The least used method was dental temporary/recruiting agencies (8.8%). Totals are more than 100% due to multiple responses. The recruiting efforts used by executive directors of CHCs gathered applicant responses in a wide range from zero to thirty, with a median number of 4 applicants. Offers made to applicants ranged from zero to 7, with a median number of 1 offer. Reasons cited for applicants rejecting job offers were primarily inadequate salary/benefits (71.0%), and location of the CHC (51.6%). The fact that no loan repayment was available was indicated for 22.6% of the rejected offers. Salaries reported by executive directors were grouped by experience of the dentist, from entry level to ten years or more of experience. Also, data were requested for the highest and lowest amounts currently being paid to contract dentists (self-employed) versus highest and lowest salary amounts for employed dentists. Totals are shown in Table 5. TABLE 5 Budgeted Salary Range Reported by Executive Directors n Mean Median Std. Deviation Entry 71 77,732 78,000 15,181 1-5 Yrs 58 86,456 85,000 19,078 5-10 Yrs 46 91,421 90,000 21,489 >10 Yrs 40 95,564 90,000 22,813 Lowest and Highest Dentist Salaries Reported by Executive Directors n Mean Median Std. Deviation Lowest Paid FTE Dentist 138 79,075 78,000 15,845 Highest Paid FTE Dentist 118 90,913 90,000 18,085 Lowest and Highest Dentist Contract Wages (Non-Employee) n Mean Median Std. Deviation Annualized Lowest Contract 19 98,393 93,600 27,273 Annualized Highest Contract 21 122,978 104,000 59,445 The executive directors’ reported salary ranges are comparable to the dentists’ selfreported salary ranges in Table 3, while contract labor wages were higher. Benefits and other perquisites reported by the executive directors are summarized in Table 6. 8 TABLE 6 Number of Vacation Days, Holidays, CE Benefits Reported by Executive Directors Number paid holidays Number of vacation days CE Dollar Amount Mean 9.7 17.7 Lowest Paid St. Dev. 2.1 5.6 n 131 131 Mean 9.8 19.6 1,542 806 109 1,720 Highest Paid St. Dev. 2.2 5.6 770 n 112 111 88 Executive Director Report of Other Selected Dentist Benefits Percentages Answering Yes Lowest Paid Highest Paid Dentist Dentist Drug License Fee Reimbursed/Paid 66.1 (74/112) 83.7 (72/86) Dental License Fee Reimbursed/Paid 66.7 (78/117) 81.8 (72/88) Malpractice Insurance 89.8 (106/118) 95.7 (88/92) Reimbursed/Paid 403b or Other Retirement Plan Offered 92.3 (120/130) 92.8 (103/111) Medical/Dental Insurance Provided 97.7 (127/130) 99.1 (106/107) Other Insurance—Disability/Life 94.9 (111/117) 96.9 (95/98) CE Allowance, no amount specified 94.6 (123/130) 94.6 (106/112) Discussion This study suggests that several factors other than salary and benefits are the determinants for retention of existing dental personnel--both staff dentists and dental directors, and that there did seem to be a high number of unfilled dentist positions in Community and Migrant Health Centers at the time of this survey. Almost half of all executive directors responding to the survey reported an unfilled vacancy in the dental component of the CHC. The three main reasons that job offers made to prospective dentists were rejected was reported by executive directors to be 1) applicants think the salary/benefits offered were inadequate, 2) applicants didn’t like the location of the CHC and 3) no loan repayment was available at the particular CHC site. While it is very understandable that a person might turn down a job offer if the salary was inadequate, it is unclear why dentists would go through the application process to interview at a location they did not like, unless hopes of a higher than average salary might compensate for an undesirable location. Similarly, one would think that if loan repayment were critical to dentists seeking employment, they would inquire before interviewing for a position in a center that could not offer that benefit. Findings from this survey seem to suggest that salary, benefits, and the opportunity for amelioration of high educational debts, while important in attracting new recruits to the Community Health Center environment, are not the only significant factors in determining retention of existing 9 dental personnel. There was no significant difference in the salaries currently being earned by dentists who plan to remain in CHC dentistry versus those who do not. However, this study found that length of service was a major determinant. This may reflect the assumption that those who can adapt to the system of dental care delivery in a CHC setting are self-selecting for retention, while those who do not adapt are intending to exit. The data would suggest that this occurs in the first few years of CHC experience. Responses to other job satisfaction determinants are interesting in that quality of facility, numbers and quality of assistants, and other day to day operating activities of practice in CHC dental clinics did not appear to significantly affect the retention of existing personnel. Neither did the level of benefits such as time off, CE allowances, insurance coverage, etc., appear to affect retention to a significant degree. However, freedom to exercise professional judgment was highly rated among dentists. In general, those dentists who perceive this freedom to be lacking were significantly more likely to indicate a desire to leave the CHC practice. In particular, the degree of availability of specialty referral options, and level of cooperation from both the administration and the board of directors were significant factors dividing those who intend to stay from those who intend to leave. Clearly, there appears to be a need for communication between dentists and their non-dental administrators and members of the boards of directors addressing each group’s expectations and the ability to fulfill those expectations in a system with limited resources. The finding that dentists who express an altruistic motivation to treat the underserved are more easily retained in CHCs is not surprising since other studies have shown similar results (4,5,6). This finding should only strengthen the efforts already in place to recruit future health care providers from the underserved and underrepresented communities to which they will more likely return at some point in their careers (4). However, loan repayment may not be the best method for attracting health care providers in general, and dentists in particular, to underserved areas. The finding that dentists who highly ranked loan repayment as a reason for choosing employment in CHC dentistry were up to 5 times more likely to leave the CHC setting than stay is intriguing. One explanation could be that a dentist may have been promised loan repayment if a position is accepted at a particular Community Health Center, but the repayment does not occur. The shifting sands of HPSA (Health Professions Shortage Area) status for any given CHC, eligibility for qualifying for loan repayment programs, and chronic underfunding of loan repayment “slots” for designated HPSAs are possible contributing factors to this finding. After a couple of years the dentist, burdened with student loans, cannot survive on the salary being offered and decides to leave for the greener pastures of private practice. Clearly there needs to be a more reliable way to ensure that loan repayment, if available, will be delivered in a timely manner to those who depend on that program to earn a livelihood. And certainly, recruiters or executive directors must not offer the carrot of loan repayment to simply “fill a position” knowing that there is a possibility that it may not happen. Conversely, this finding may indicate that those who rated loan repayment highly and have benefited from loan repayment to its maximum extent simply move on to other areas of interest, having paid off their educational debts in a short period of time. However, is private practice the best option for dentist employment? Comparing compensation from a dental position in a community health center to solo ownership of a 10 private practice, a salaried position in academia, private non-owner dentist positions, and other government related jobs (IHS, PHS, Armed Services) is a formidable task fraught with numerous variables which confound the bottom line. For example, most community health centers and academic teaching positions have benefits that are provided by the employer. Vacation days, sick leave, company paid medical insurance and other perquisites can add thousands of dollars in value to a job that a private practitioner or private nonowner dentist would have to self-finance. Similarly, allowances for housing and special pay or loan repayment through government service may be non-taxable and would therefore equate to a higher taxable salary offered in the private sector. In addition, self-employed practitioner income varies by the number of hours worked. Therefore, persons who choose to take more vacation time or who consider full-time practice to be less than the usual 40 hour work week may have a different compensation per hour than those in standard salaried positions. Perhaps more efforts should be made by CHC recruiters to present potential dentist employees with a more accurate comparison of CHC compensation, either with or without loan repayment benefits. Many question the degree to which salaries offered in other areas of dental practice adversely affect the recruitment and retention of dentists in Community and Migrant Health Centers. While this survey was not designed to specifically answer this question, a brief salary comparison is presented in Table 7. Net income figures for private unincorporated sole proprietors and nonowner dentists are from the ADA 2000 Survey of Dental Practice, Income from the Private Practice of Dentistry (7), using data collected in 1999. Faculty salaries are provided from the ADEA Faculty Salary Survey, Guaranteed Annual Salary: 2000-2001(8). At the time of this writing, these are the most recent published salaries available and are reasonably contemporaneous with the ADA survey numbers. Military and Indian Health Service compensation methodologies are readily available from their respective websites and are not included in this comparison. CHC dentist salaries are based on information received in the Spring of 2002. 11 Table 7 Comparison of Salaries of Selected Dentist Positions Employment Status General Practitioners: Nonowner Dentist (Employees/Associates) General Practitioners: Sole Proprietors (Unincorporated) Full-Time Faculty: Guaranteed Annual Salary Assistant Professor (All Dental Schools) Full-Time Faculty: Guaranteed Annual Salary Associate Professor (All Dental Schools) Staff Dentist Community Health Center (All Regions) Dental Director Community Health Center (All Regions) Mean 1st Q Median 3rd Q S.D. 97,740 65,000 90,000 120,000 49,840 46 142,720 85,000 128,000 186,920 82,930 391 70,545 60,000 70,000 79,363 NA 764 82,968 70,955 81,559 93,424 NA 641 81,604 70,000 80,000 91,250 23,775 178 91,653 78,000 90,000 102,000 23,038 179 N Limitations of the Study The purpose of this study was to determine the salaries currently being offered to dentists in Community Health Centers, determine if the salaries vary significantly by region, and quantify the extent of job vacancies in CHC dental components. Attempts were made to determine explanations why dentists stay or leave CHC dental positions based on associations derived from job satisfaction determinants. While the response rate from the dentist mailing was high (73.8%), the response rate was much lower from the executive directors (46.1%). Due to limited funding, no follow-up surveys were sent to nonrespondents. Executive directors who responded may exhibit some selection bias, i.e., perhaps more of the troubled program directors bothered to respond to a questionnaire about dental vacancies. The true rate may be more or less than the responses indicate. Also, the numbers of responses to questions regarding how many applicants responded to recruitment efforts, how many job offers were made, and why job offers were rejected are dependent on recollection and thus inherently subjective. Attempts to analyze salaries by region were affected by unexpected difficulties. Since the surveys were not marked or identified in any way, to encourage candor in divulging 12 salary information, the original plan to track regional responses by ZIP code was thwarted by an absence of any postmark on approximately 25% of the postage paid return envelopes. As a result, the power of our regional salary data was reduced. Since salary data is highly confidential, it was decided that the trade off between a completely candid salary disclosure versus completely trackable responses was worth the loss of power of the regional data. Finally, this survey did not reach dentists who have already left the community health care system. While much valuable information was obtained from existing dental providers in CHC practice, we cannot know with more certainty the real reasons others have already left. Conclusions and Recommendations It is highly desirable to continually monitor factors associated with retention and recruitment of dentists in community and migrant health center clinics. CHC administrators must periodically be kept informed of the current conditions in the dental practice marketplace, know what other CHCs are budgeting for dentist positions, and receive candid feedback on dentist/health center administration relations. Therefore, funding should be budgeted for bi-annual salary and retention surveys similar to the one which generated this study and analysis. Future studies could have follow-up costs built in to the budget to pursue higher response rates by doing second mailings or follow-up phone calls to non-respondents. Also, additional information could be obtained from dentists who leave community health center practice in the form of a standardized anonymous exit survey, which could be delivered to Regional HRSA consultants for review. This tactic might be especially useful for particular geographic areas or specific CHCs within regions which have high turnover rates of dental providers. Executive directors or dental personnel recruiters should be able to effectively convey the true compensation of an offered dental position. Most applicants will be comparing any salary offer with the salaries that other friends or associates that they personally know may be receiving. However, if the CHC representative can show how the salary and benefits offered translate into a comparable self-employed salary amount, the applicant may be pleasantly surprised at the calculation presented. A “total compensation information package”, which takes into account matching FICA payments, value of paid time off, dollar amount of medical, dental, or other insurance provided paid on behalf of the employee, and professionally related expenses that are reimbursed or defrayed, should be readily presentable to any qualified applicant seeking employment with a CHC. Persons hired as dental directors should be given a clear job description of the duties involved in being a dental director, including administrative requirements that any particular CHC may require. Many clinicians recruited from private practice may be unfamiliar which those types of duties and may underestimate the amount of time needed to perform them. Similarly, executive directors must allow appropriate amounts of time for administrative duties and alter their expectations of numbers of patients seen or amount of procedures performed clinically by the dental director accordingly. Dental 13 directors should feel free to communicate their perceptions of adequate amounts of time for administrative duties without fear of reprisals from the administration and without inappropriate self-criticism. Finally, persons in charge of recruitment of dentists for CHC employment must use the promise of loan repayment cautiously and honestly for new dentists, who value such a benefit very highly. Students currently exiting dental schools with up to $100,000 in educational loans cannot realistically be expected to accept salaries far below the private sector market for long periods of time. Loan repayment promised but not delivered leaves a bitter taste in the mouths of those who need it. 14 References: 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, 2000. 2. US General Accounting Office: Oral health: dental disease is a chronic problem among low-income populations. Washington, DC: US General Accounting Office, 2000; pub no GAO/HEHS-00-149. 3. Marwick C. National Health Service Corps faces reauthorization during a risky time. JAMA 2000;283:2461-2. 4. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski JJ, Gayle JA. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of underserved populations. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1225-8. 5. Mofidi M, Konrad TR, Porterfield DS, Niska R, Wells B. Provision of care to the underserved populations by National Health Service Corps alumni dentists. J Public Health Dent 2002;62:106-7. 6. Porterfield D, Konrad TR, Leysieffer K, et al. Caring for the underserved: current practice of alumni of the National Health Service Corps. J Health Care Poor Underserved (in press). 7. American Dental Association, Survey Center. The 2000 Survey of Dental Practice: Income from the Private Practice of Dentistry. Chicago, ADA, January 2002. 8. American Dental Education Association, Center for Educational Policy and Research. Faculty Salary Survey, Summary Report: Guaranteed Annual Salary: 2000-2001, Total Compensation: 1999-2000. Washington, DC, 15 Appendix 1 Survey questions for dentists: Confidential 1. When did you graduate from dental school?______________ 2. How long have you been practicing dentistry (minimum 20 hours/week)? a. Less than one year c. >5 but <10 years b. >1 but <5 years d. More than 10 years 3. What was your primary dental practice activity immediately prior to practicing in a Community Health Care setting? a. Dental Student b. Graduate program/specialty program c. Private practice/owner or partner d. Private practice/associate or employee e. Commissioned Officer in Military or Public Health Service f. Dentist with the Department of Veterans Affairs g. Retired 4. What were your primary reasons for choosing a practice opportunity with a Community Health Care organization? (Please rank your top five choices in order of their importance to you.) _____a. Felt a mission to the dentally underserved population. _____b. Wished to offer oral health care within an interdisciplinary environment. _____c. Wished to practice dentistry in a community based setting. _____d. Did not want to invest capital in a private practice. _____e. Attracted by work schedule/leave policies of Community Health Center. _____f. Loan repayment was offered or promised to you in Community Health Care dentistry. _____g. Sold private practice, or retired from government service _____h. Unsatisfied with associate/employee dentist arrangements currently available. _____i. Other_____________________________________________________ 5. How do you perceive your professional freedom in the treatment of Community Health Center dental patients? a. Completely free to exercise professional judgment. b. Not completely free to exercise professional judgment. 6. If not completely free to exercise professional judgment, which of the following apply. (choose all that apply) If completely free, skip to question 7. a. degree of patient compliance with treatment recommendations or appointment attendance. b. level of cooperation from administration (executive director or chief financial officer) c. level of cooperation from the Community Health Center board of directors. d. budgetary restraints involving certain laboratory procedures or specialty procedures. e. degree of availability of specialty referral options, i.e. endodontics, periodontics, oral surgery, or orthodontics. 7. What is your current position in the Community Health Center dental department? a. Staff dentist b. Dental director If you are the dental director (or if you are the only dentist) please answer the following four questions. Otherwise, proceed to question #12. 8. Do you feel you have enough administrative time set aside out of the clinic to manage operations of the dental component of the Community Health Center? a. Plenty of time b. Not enough time c. No time at all 9. How many clinic hours do you usually work on a weekly basis?_____________ 10. How many administrative hours do you usually work on a weekly basis?________ 16 11. What is the job title of the person to whom are you accountable?______________ (e.g. executive director, director of operations, medical director, or other.) 12. Are you offered continuing education time and expense reimbursement to maintain your credentials? a. Yes #Days__________$___________. b. No time or expense reimbursement. 13. How many days are currently offered to you for vacation time? ___________ 14. Is your sick leave/personal leave time adequate? a. Yes b. No 15. Are your medical insurance benefits adequate? a. Yes b. No 16. Are you offered any retirement benefits through a 403b plan or similar plan? a. Yes b. No 17. Is there a salary incentive (production incentive) program in place? a. Yes b. No 18. What is your approximate pre-tax salary, not including benefits, on a yearly basis. Pre-tax salary is defined as gross wages before income tax or Social Security/Medicare taxes are deducted. (If part-time, extrapolate to full-time yearly amount.) $___________ 19. What is your specialty? a. General dentistry b. Pediatric dentist c. Public Health Dentist (M.P.H. or equivalent)) 20. Did you have advanced training in general dentistry Yes If yes, what kind of program was it? GPR AEGD No 21. How many years have you been in Community Health Care dentistry. _________ 22. How would you rate your facility overall in terms of physical building, equipment, supplies, and appearance? a. Very good b. Good c. Adequate d. Needs improvement e. Poor 23. Are you required to participate in night or weekend on-call responsibilities: a. Too much c. Seldom b. Often d. Never 24. Please rate the following regarding dental clinic support. a. Number of dental assistants. b. Quality of dental assistants. c. Clerical support: reception, records, billing. d. Administrative support. Adequate Adequate Adequate Adequate 25. Do you intend to remain in Community Health Center based dentistry? a. Yes b. No 26. If answer is no to question 25, how soon do you plan to leave? a. As soon as another opportunity opens up. b. Within the next year. c. Within the next 2-5 years. d. Upon retirement. 17 Inadequate Inadequate Inadequate Inadequate Appendix 2 Executive Director Survey Questions 1. How many dentist FTEs are currently employed in your clinic?__________ 2. How many are full-time (30 or more hours per week)?_________________ 3. How many are part-time (less than 30 hours per week)?_______________ 4. How many dentist positions (FTE) are currently budgeted?_____________ If no dentist positions are vacant, please skip to question #17. For each vacancy, please answer this series of six questions. 5. What is the duration of vacancy 1 as of this survey date? a. Less than 6 months c. 12-24 months b. 6-12 months d. More than 24 months 6. What methods have been used to recruit for this vacant position? (Circle letters of all that apply.) a. Newspaper advertisement b. Dental journal (state or national) advertisement c. Posting at dental schools d. Speaking to students/residents about community based dentistry e. Displays at job fairs/dental conventions f. Dental temporary agencies or recruiting agencies g. Working with National Health Service Corps h. Networking through Primary Care Associations i. CHC website postings j. Other_____________________________________________ 7. How many applicants have responded to any of the above methods during the entire time since the position became vacant?_________________ 8. How many applicants have been made firm offers for the vacancy?_________ 9. If firm offers have been made but rejected, what were the reasons given? (circle letters of all that apply.) a. salary/benefits inadequate b. location of Community Health Center c. level of staffing of the dental clinic d. condition of equipment of dental clinic e. no loan repayment available f. other__________________________ 10. Current budgeted amount for first dentist vacancy, including fringes. a. Entry level position $ _______ b. One to five years experience $ _______ c. Five to ten years experience $ _______ d. More than ten years experience$ _______ 18 If only one position is vacant, please skip to question 17. 11. What is the duration of vacancy 2 as of today? a. Less than 6 months c. 12-24 months b. 6-12 months d. More than 24 months 12. What methods have been used to recruit for this vacant position? (Circle letters of all that apply.) a. Newspaper advertisement b. Dental journal (state or national) advertisement c. Posting at dental schools d. Speaking to students/residents about community based dentistry e. Displays at job fairs/dental conventions f. Dental temporary agencies or recruiting agencies g. Working with National Health Service Corps h. Networking through Primary Care Associations i. CHC website postings j. Other_____________________________________________ 13. How many applicants have responded to any of the above methods during the entire time since the position became vacant?_________________ 14. How many applicants have been made firm offers for the vacancy?______ 15. If offers have been made but rejected, what were the reasons given. (check all that apply) a. salary/benefits inadequate b. location of Community Health Center c. level of staffing of the dental clinic d. condition of equipment of dental clinic e. no loan repayment available f. other__________________________ 16. Current budgeted amount for second dentist vacancy, including fringes. a. Entry level position $ _______ b. One to five years experience $ _______ c. Five to ten years experience $ _______ d. More than ten years experience$ _______ 17. Are there any contract labor dentists retained on staff? Yes No If yes, lowest annualized contract amount (2080 Hours) $________ Highest annualized contract amount (2080 Hours) 19 $________ 18. Current lowest paid FTE dentist. a. salary $ _________ b. medical/dental insurance benefits $ _________ c. other insurance disability, life $ _________ d. # paid holidays ________ e. # vacation days ________ f. Retirement benefits (403b or other) g. malpractice insurance reimbursement? Yes No $ ________ h. dental license fee reimbursement $ ________ i. drug license fee reimbursement $ _________ j. Continuing education allowance $ __________ k. Level of experience of this dentist (since dental school graduation) 1. one year or less 2. one to five years 3. five to ten years 4. more than ten years 19. Current highest paid FTE dentist: a. salary $ _________ b. medical/dental insurance benefits $ _________ c. other insurance disability, life $ _________ d. # paid holidays ________ e. # vacation days f. Retirement benefits (403b or other) ________ Yes No g. malpractice insurance reimbursement? $ ________ h. dental license fee reimbursement $ ________ i. drug license fee reimbursement $ _________ j. Continuing education allowance $__________ k. Level of experience of this dentist (since dental school graduation) 1. one year or less 2. one to five years . 20 3. five to ten years 4. more than ten years Appendix 3 Staff Dentist vs. Dental Director Salaries By Region Staff Dentist Region 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 N 5 14 10 17 23 12 7 9 6 34 Dental Director Mean 75480.00 72328.57 69520.00 76500.00 70760.87 77168.33 98000.00 76404.78 93314.83 98905.88 S.D. 8071.679 17399.27 4942.289 15650.48 17576.37 19560.12 45574.12 17884.36 13103.05 23608.24 Median 80000.00 75000.00 68350.00 79000.00 75000.00 71500.00 80000.00 78000.00 90416.50 94250.00 N 13 10 11 24 14 25 4 6 10 18 Mean. 87769.23 82900.00 83547.27 84992.50 86107.14 91597.96 117750.00 86354.17 106219.80 111388.90 S.D. 22398.49 20100.86 13881.38 16430.08 18555.72 20893.03 62516.00 13514.90 19651.64 22656.36 Median 85000.00 92000.00 85000.00 81500.00 90500.00 90000.00 93000.00 82062.50 99400.00 104000.00 Pre-Tax Salary By Region: All Respondents Region Mean Median Std. Dev. Minimum Maximum 1 86231.57 80000.00 21121.26 60000.00 139000.00 2 76733.33 84750.00 18909.22 38500.00 98000.00 3 76867.61 75000.00 12604.43 58000.00 100000.00 4 81471.21 80000.00 16466.25 40000.00 118000.00 5 76447.36 80000.00 18989.60 30000.00 113000.00 6 86918.08 85000.00 21326.33 50000.00 146000.00 7 101416.66 82000.00 49590.06 60000.00 210000.00 8 79891.75 78062.50 16097.01 40000.00 109000.00 9 101380.43 95400.00 18181.76 80000.00 141000.00 10 103226.92 98000.00 23826.47 45000.00 160000.00 21 n 18 24 21 41 37 37 11 15 16 52