resource dependency theory in a nutshell

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND

BEHAVIOR, 6 (3), 354-373 FALL 2003

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH

RELATIONS: A RESOURCE DEPENDENCE PERSPECTIVE

Mahommad Rafiqul Islam*

ABSTRACT

. This article examines the application of “resource dependency theory” to transnational corporations (TNCs) operating in host countries like

Bangladesh to explain the relationship between the TNCs and Bangladesh. Data indicate that while the TNCs’ participation in a third world host country is encouraged primarily for promoting its economic development, TNCs are mainly attracted by market size, purchasing capacities (determined mainly by

GNP) of the population, and stable political condition of the country. Although examination of the application of resource dependency theory provides some insights into understanding the complicated relationship between TNCs and

Bangladesh, several other factors, not explained by resource dependency theory, help explain the behavior of TNCs in a host country.

INTRODUCTION

The transnational corporations (TNCs), which are alternatively known as “multinational”, “international” or “global” companies, play a catalytic role in the economic development of developing countries, although the relationship between the transnational corporations and host countries (especially developing countries) often is described as controversial (Al-Daeaj, Ebrahimi, Thibodeaux & Nasif, 1999).

Transnational corporations have a significant impact on international production and investment as well as on the growth of culture, communication, education, trade, science and technology in developing countries (Al-Daeaj, et al., 1999, p. 76; Kumar, 1980; Reiffers, 1982;

-----------------------

* Mahommad Rafiqul Islam is a Ph.D. Candidate, School of Public

Administration, Florida Atlantic University; and Assistant Professor of Politics and Public Administration, Islamic University, Kushtia, Bangladesh. His research interests are in organization theory and behavior, personnel management, and bureaucracy, reforms and development in developing countries.

Copyright © 2003 by PrAcademics Press

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS

Reza, 1995). Al-Daeaj et al. identify six major sources of transnational corporation (TNC)-host country (HC) conflict that include ownership, local unemployment, transfer of technology, exploitation of natural resources, bribery and foreign exchange shortages. The sources of conflict are often the result of power differential between the host country and the TNC (Al-Daeaj, et al., 1999, p. 76). However, the power game of politics between the TNCs and HCs is exercised for control or possession of resources.

Since the effects of TNCs on HCs (especially developing countries) are widely debated (Al-Daeaj, et al., 1999, p. 76), the TNC-HC relations are not beyond criticism. Some proponents of TNCs/MNCs claim that third world host countries harvest several benefits from these institutions.

The benefits from the TNCs gained by the HCs include higher wages paid by the TNCs than by the domestic firms, fostering higher national income for developing nations in the long run (Barnet & Muller, 1974;

Harrison, 1994; Patel, 1974) and so on, while disadvantages obtained from the TNCs are many that include extraction or drainage of resources from HCs (Barnet & Muller, 1974; Kumar, 1980; Meleka, 1985; Reza,

1995), political bribery, anti-social activities (Newman, 1979; Reza,

1995) and the like. For example, Sadrel Reza, an economist of

Bangladesh, compares TNCs to “suction pumps” in the form of sinister agents of capitalistic imperialism designed to drain resources out of the developing countries like Bangladesh (Reza, 1995, p. 13). However, both the proponents and the opponents of TNCs should agree that the rate and form of growth of the important sectors of developing countries are often determined significantly by the TNCs, acting outside the control of the host governments (Kumar, 1980; Reza, 1995, p. 13). In the process, they distort the development pattern and impose elitist products and capitalintensive techniques on developing countries with a view to excessively exploring technological/marketing rents (Patel, 1974; Reza, 1995, p. 13).

TNCs mainly invest capital in HCs for making profits. So, gaining profits by extracting resources from HCs is the fundamental motive of

TNCs.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The major objective of this paper is to justify the application of

“resource dependency theory” to TNCs operating in host countries like

Bangladesh, because the relationship between TNCs and Bangladesh can be understood in terms of the applicability of resource dependency

355

356 ISLAM theory. However, in order to justify the application of resource dependency theory to transnational corporations in Bangladesh, this paper makes an attempt to explore answers to the following questions, and provides analysis based on these questions:

1.

What is resource dependency theory?

2.

What does resource dependency theory say about organizational behavior?

3.

How does resource dependency theory apply to TNCs?

4.

How does resource dependency theory apply to TNCs operating in

Bangladesh?

5.

What other factors, not explained by resource dependency theory, help explain the behavior of TNCs in host country like

Bangladesh?

DATA SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY FOR DATA ANALYSIS

In order to analyze TNC-Bangladesh relations or to justify the application of resource dependency theory to transnational corporations in a host country like Bangladesh, data have been collected from both primary and secondary sources. Since transnational corporations especially invest a lion’s share of money in host countries through foreign direct investment (FDI), data regarding the FDI flow in

Bangladesh since the 1971 fiscal year to 2000-2001 fiscal year have been collected directly from the Board of Investment, Government of the

People’s Republic of Bangladesh. However, data from the secondary sources include mainly different journal articles and a number of books.

RESOURCE DEPENDENCY THEORY IN A NUTSHELL

Resource dependency theory has been proposed by organization theorists Jeffrey Pfeffer and Gerald R. Salancik who explain organizations in terms of their interdependence with their environment

(Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 62; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Daft, 2001, p.

146). However, resource dependency theory conceptualizes that organizations are interdependent with their environment or other organizations for their survival. As organizations are not self-directed and self-dependent (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 62; Daft, 2001, pp. 146-

147), they need resources for their survival. These resources include

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS money, materials, personnel, information and technology. The degree or extent of this resource dependency varies from one organization to the next. For example, a financial organization such as a bank will depend heavily on the outside environment for money, while another organization such as a manufacturing plant may depend more on the quality and availability of personnel. However, capital in the form of money seems to be the most important resource without which no organization can survive. Capital can be viewed as the fuel of organization. But capital alone cannot solve all the problems.

Organizations require a free flow of information that enables them to make better decisions. In fact, all of these resources, including money, materials/equipment, personnel, technology and information are important ingredients of the organizational resources all organizations need to effectively function. If organizations lack any of these resources, they must effectively interact with others who control the resources

(Pugh & Hickson, 1997; Ulrich & Barney, 1984).

Jeffrey Pfeffer and

Gerald Salancik (1978) think that interdependence with others lies in the availability of resources and the demand for them. This interdependence may take the form of direct dependence of the seller organization or its customers or the mutual dependence of seller organizations on potential customers for whom they compete (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 62).

According to resource dependency theory, three conditions are responsible for defining the extent or degree of dependency of an organization (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Pugh & Hickson, 1997).

The first condition is the importance of resource in the organization. The importance of resource in organization is determined by taking into account the demands and supply of resource or by assessing the severe consequences if resources were not available (Pfeffer & Salancik; Pugh

& Hickson, p. 62). The second condition is how much discretion those who control a resource have over its allocation of use. This condition also suggests that if those who control a resource have completely free access to it and can make the rules about it, then an organization that needs it can be put in a highly dependent position (Pugh & Hickson, p.

62; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).

The third condition is the degree to which those who control a resource enjoy a monopoly. Whether an organization that needs resources has an alternative source or substitute is also vitally important.

Indeed, the potential for one organization’s influencing another organization emerges from its discretionary control over resources

357

358 ISLAM needed by that other and another organization’s dependence on the resource, lack of compensating resources, or access to alternative sources. Others on whom an organization depends may not be dependable. Consequently, the success or effectiveness of a dependent organization is determined more by how well it mediates these dependencies than by external measures of efficiency of financial or similar nature (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 63).

RESOURCE DEPENDENCY THEORY AND ORGANIZATIONAL

BEHAVIOR

The following section seeks to answer the question: What does resource dependency theory say about organizational behavior? In examining what resource dependency theory says about organizational behavior or how resource dependency effects organizational behavior, it is imperative to know what organizational behavior actually is.

Organizational behavior is the study of human behavior, attitudes and performance in organizations (Hellriegel, Slocum & Woodman, 1998, p.

4). Broadly speaking, organizational behavior encompasses individual attitudes, communication patterns, team processes, personality, skills and abilities, conflict, political behavior, values and norms, religious beliefs; decision making and leadership patterns of individuals within the organization. It is also linked with ethics, global perspective, technology and diversity issues (Hellriegel, Slocum & Woodman, 1998, p. 18).

Resource dependency theory is about the dependency relationship of one organization with the external environment for resources. These resources on which organizations depend are money, material/equipment, personnel, information, etc. Resource dependency theory emphasizes the needs for personnel, application of their talents, skills and experience for the smooth running of the organization that embraces the components of organizational behavior (Pugh & Hickson,

1997, pp. 62-62; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). Without multidimensional or free flow of information and sophisticated technology, modern organizations face difficulty surviving in the competitive market place.

So, they have to depend on information and technology resources.

Resource dependency theory reveals the fact that organizational behavior is influenced by information and technology (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p.

62; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), in the absence of which organizational goals are impeded and productivity is hindered.

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS

Organizational behavior is largely affected by the amount of money invested in the organization. The more money invested in organization, the larger the size of the organization is and the less dependent it will be upon the external environment. The amount of money invested in organization also determines the quality and standards of goods and services as well as the quality of personnel. Resource dependency theory also says that those organizations that depend on other organizations or environments for resources are controlled by those organizations on whom they are dependent. In such process of dependency, the behaviors of dependent organizations are regulated by the organizations on whom they depend (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, pp. 62-63; Pfeffer & Salancik,

1978). As organizations cannot be self-dependent and autonomous, they have to depend upon other organizations. In this way, the dependent organizations need to balance their dependency with other organizations in order to get rid of the control of the other organizations on which the dependent organizations rely (Pugh & Hickson, 1997; Pfeffer &

Salancik, 1978).

It goes without saying that the decision making process is an important ingredient of organizational behavior through which administrators/decision makers set relevant strategies or devices to solve organizational conflicts or problems for attaining its goals. In this respect, the “resource dependency theory” of Pfeffer & Salancik (1978) advocates four kinds of strategies that an organization may use to balance its dependencies (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 63). The four possible strategies that have an effect on organizational behavior through balancing its dependencies are as follows:

1.

Adapting to or altering external constraints

2.

Altering the interdependencies by merger, diversification or growth

3.

Negotiating the environment by interlocking directorships or joint ventures with other organizations or by other associations; and

4.

Changing the legality or legitimacy of environment by political action.

The first strategy--adapting to or altering external constraints-- suggests that organization can either accommodate or adjust to the external constraints or difficulties on a priority basis. This strategy also suggests that if the organization does not comply with external

359

360 ISLAM environments or constraints because of legal restrictions or any difficulty, it can minimize its dependence by stocks of material or money

(Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Pugh & Hickson, 1997).

The second type of strategy indicates that the organization can either alter its interdependent relationships by merging with other organizations or diversifying its dependencies or expanding the size and power of the organization. In the process of its merging with other organizations the resources are controlled by the single organization. Diversification helps an organization reduce its over-dependence in any particular field.

Growth in size increases the power of an organization relative to others that improves its stability and survivality than profitability (Pfeffer &

Salancik, 1978; Pugh & Hickson, 1997).

The third type of strategy that “resource dependency theory” advocates is negotiating the environment either by interlocking directorship or joint ventures with other organizations, which is a more common strategy than total absorption by merger. Interlocking directorship is a process whereby boards include members of the boards of other organizations, trade agreements, memberships in trade associations and coordinating industry councils and advisory bodies

(Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Pugh & Hickson, 1997). On the other hand, joint venture is a system in which two or more organizations work together based on their mutual commitment (Oliver, 1990; Pan & Li,

2000; Pugh & Hickson, 1997).

The fourth and final strategy that “resource dependency theory” suggests about organizational behavior for balancing dependency is changing the legality or legitimacy of organizational behavior by political action. By and large, organizations resort to political action when all other strategies are closed to them. They seek to get and sustain favorable taxation, or tariffs or subsidiaries, or licensing of themselves or other members, or they charge others with violating regulations. In their

“resource dependency” theory, Pfeffer and Salancik suggest that in order to balance interdependency, organizations can adopt political action by means of executive succession- that is, removal of executives and their replacement by others (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).

HOW DOES RESOURCE DEPENDENCY THEORY APPLY TO TNCs?

Resource dependency theory can apply to transnational corporations

(TNCs) in a variety of ways. According to resource dependency theory,

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS no organization can operate without resources. Organizations have to depend on the environment or other organizations for resources. So does the TNC. TNCs are established beyond their national boundaries in collaboration with other organizations of the host countries (Lecraw &

Morrison, 1991, p. 22). Through their diverse networks of interdependencies, TNCs invest money, machineries and technical knowhow in the host countries. In return, they have to depend on the markets and raw materials of the HCs. However, by introducing their integrated and cooperative strategies and perspectives of dispersed and interdependent assets and resources, TNCs try to maximize the performance in its worldwide operations (Pugh & Hickson, 1997; Ulrich

& Barney, 1984).

In dependency relationships, TNCs possess a set of ownership advantages, such as proprietary product and process technology, an international or national distribution system, brand names, trademarks and marketing expertise, information sources, and an information control evaluation system, production expertise, access to capital, broadly defined management skills and expertise in operating in different HCs. In exploiting these ownership advantages, TNCs are faced with a varied opportunity set, including investing in different countries (including the home country) and accessing HC markets through a host of operating modes. In this process, the HCs have to depend on the TNCs for experts, for economic and trade diversification, for investment capital, and for increasingly sophisticated product and process technology. Indeed, the goal of HCs in their relationships with TNCs is to maximize the country development (Encarnation & Vachani, 1985; Lall & Streeten, 1990;

Lecraw & Morrison, 1991).

Resource dependency theory suggests that organizations can balance their dependency with other organizations/environment by applying appropriate and feasible strategies (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 63; Pfeffer

& Salancik, 1978). In this respect, TNCs generally balance their dependency through bargaining or negotiating with the HCs (Encarnation

& Vachani, 1985, p. 153; Lecraw & Morrison, 1991, p. 22). In this relationship, both the TNC and HC have reserve positions equal to the value to them of their next best alternative relationship. For a TNC its reserve position depends on the value of its ownership advantages in their next best alternative use. A TNC recognizes that ownership advantages are value creating and will strive to maximize value through

361

362 ISLAM effective negotiations with a HC (Encarnation & Vachani, 1985, p. 153;

Lecraw & Morrison, 1991, p. 22).

The application of bargaining/negotiating strategy is not a simple task. TNCs and HCs are likely to perceive the costs and benefits of their relationship on different dimensions and according to divergent assumptions (Fagre & Wells, 1982; Lecraw & Morrison, 1991). For instance, TNCs are largely concerned with the economic dimensions of their relationship with HCs, while HCs are more likely to be concerned with its social and political effects as well. More specifically, TNCs may want to maximize profits, while HCs may want to increase employment, technology transfer, increase tax revenues, increase exports and so on

(Fagre & Wells, 1982; Lecraw & Morrison, 1991; Mahini, 1988). In fact, the ultimate result of the bargaining/negotiation between the TNC and the HC relative to their maximum and reserve positions depends on their experience, abilities, skills and how they implement their policies and strategies during the negotiation process (Encarnation & Vachani, 1985, pp. 153-154; Lecraw & Morrison, 1991, 22; Fagre & Wells, 1982).

TNCs try to obtain the benefits of world-scale production for laborintensive products by building in a low wage economy while obtaining the benefits of technically sophisticated products. TNCs also require a considerable degree of functional and national specialization for balancing their dependencies. These interdependencies are designed to build self-enforcing cooperation among different units, such as when the

U.S. subsidiary depends on Japan for one range of products, while the

Japanese depends on the U.S. for another (Pugh & Hickson, 1997, p. 41).

However, it is difficult to understand whether, how or to what extent resource dependency theory can apply to TNCs since the nature and dimension of interrelationship and interdependence between the TNCs and the HCs are very complex and complicated.

APPLICABILITY OF RESOURCE DEPENDENCY THEORY TO TNCs

IN BANGLADESH

The following section attempts to answer this question: How does resource dependency theory apply to TNCs operating in Bangladesh? As mentioned earlier, resource dependency theory holds the idea of the interdependence between organizations and their environment based on resource availability. With a view to making profits, a large number of

TNCs from different countries including the U.S., Britain, Germany,

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS

Canada and Japan have been operating in Bangladesh since its independence in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI) based on equity ownership and portfolio investment based on non-equity participation. However, TNCs’ interdependence relations with the HC can be explained in terms of market size, economic growth, gross national product (GNP) and HC political conditions. If TNC is considered a dependent variable, then market size, economic growth and political conditions of the host country can be viewed as independent variables (Rashid, 1993, p. 56), because foreign investment by the TNC is affected by the political condition, market size, GNP and economic growth of the country. Market size is generally determined by the total number of consumers of a country and their purchasing capacity as well as economic growth of the country. However, this section of the paper examines foreign direct investment (FDI) by TNCs and its non-equity participation in the host country with special reference to Bangladesh as well as the factors that attract TNC investment in HC. When all these factors are considered collectively, they help explain how resource dependency theory applies to TNCs operating in HCs.

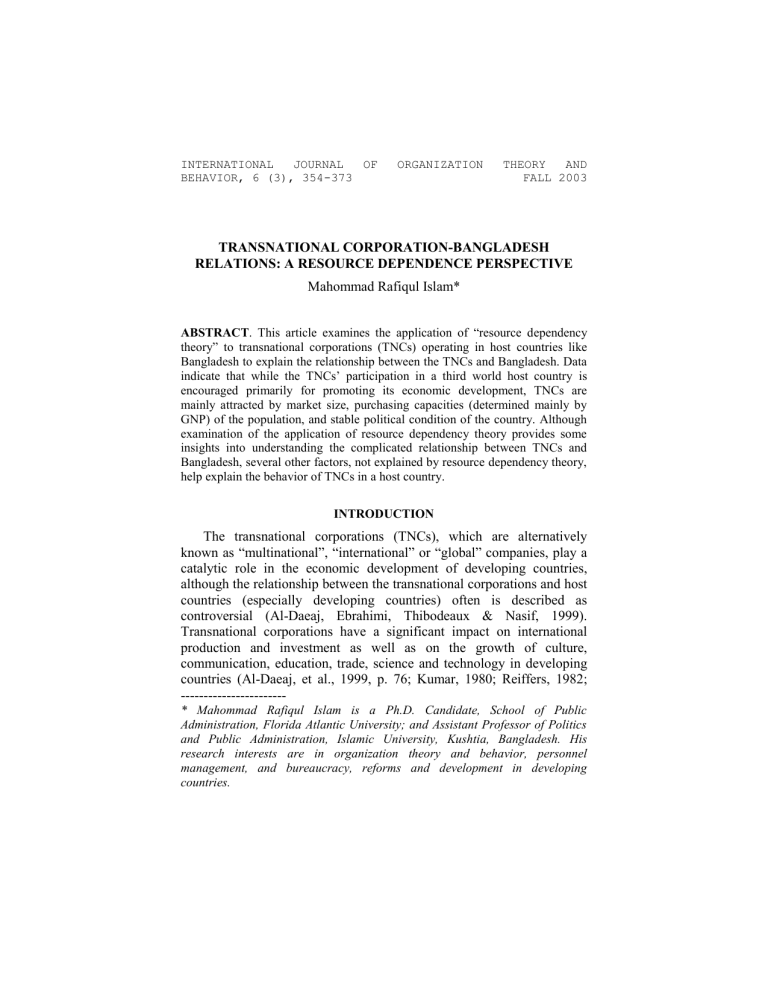

Foreign Direct Investment by TNC in Bangladesh

Since independence of Bangladesh in 1971 until today, multinational corporations (MNCs)/transnational corporations (TNCs) have been investing in different sectors of the economy in Bangladesh through foreign direct investment (FDI) with majority or minority equity participation. Table 1 of this paper indicates that from 1971 to 1996, the amount of sanctioned investments totaled about Tk.139674 1 million in current prices for a total of 575 sanctioned units. It is apparent from this figure that up to 1971 the amounts of investments were about Tk.383.69 millions in current prices for only 23 sanctioned units.

2 From 1971 to

1976, there was no trend of FDI flow in Bangladesh. This was because of the nationalization policy of industries of then government. During that period the political condition of the country was volatile; economic growth was damaged by both flood and drought, and per capita income of the population was severely decreased. So TNCs were discouraged from investing capital in the land of Bangladesh. But the political environment of Bangladesh changed after mid-August, 1975 following the downfall of the Mujib government. Therefore, from 1976 to 1982

TNCs invested about Tk.538 millions in current prices for a total of 21 sanctioned units in addition to the amount of sanctioned investment of about Tk.383 millions. Repeatedly, there was no trend in FDI flow in the

363

364

Year

Up to 1971

1972-73

1973-74

1974-75

1975-76

Sub-total

1976/77

1977/78

1978/79

1979/80

1980/81

1981/82

Sub-total

1982/83

1983/84

ISLAM country during 1981-82 due to the change of the government that occurred after assassination of President Ziaur Rahman through the fourth military coup-d’etat in the history of Bangladesh. During that time

TNCs were discouraged from investing capital for fear of incurring loss as a result of changes in the political environment in Bangladesh (Reza,

1995).

One significant feature visible from the table is that FDI by TNCs in

Bangladesh increased by leaps and bounds in 1993-1994 because of the liberalization procedures of the Industrial Policy 1991 and the stable political environment of Bangladesh (Reza, 1995).

During that time the amount of investments was about Tk.31,503 million in current prices for a total of 83 sanctioned units. During the democratic governance of

Begum Khaleda Zia from 1991 to 1996, about Tk.125,507.54 million in current prices was sanctioned through FDI by the TNCs for a total of 420 sanctioned units, almost 90% of total sanctioned investments in current prices from 1971 to 1996 (Board of Investment, Bangladesh, 2001). FDI by the TNCs in Bangladesh, which increased between 1996 and July

2001 during the regime of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, amounted to a total of Tk.466,527 million for 654 sanctioned units (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Flow of FDI in Bangladesh

Total

Sanctioned

Units*

23

0

0

0

3

2

12

0

0

23

2

2

21

9

18

No. of Units in

Production

3

2

11

0

0

23

2

1

23

0

0

0

19

8

14

Amount of Investment in the Sanctioned Units (in million taka)**

383.69

0

0

0

0

383.69

3.70

30.87

354.11

14.88

134.84

0

538.40

609.68

1,097.89

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Year

1984/85

1985/86

1986/87

1987/88

1988/89

1989/90

1990/91

Sub-total

1991/92

1992/93

Total

Sanctioned

Units*

6

5

16

17

19

NA

11

111

24

41

No. of Units in

Production

4

1

4

3

NA

NA

6

40

18

NA

Amount of Investment in the Sanctioned Units (in million taka)**

350.59

93.56

2,280.01

2,546.97

4,079.51

1,945.00

331.80

13,335.01

1245.31

954.65

1993/94

1994/95

1995/96

Sub-total

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

83

145

127

420

138

140

161

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

31,503.58

29,196.00

62,608.00

125,507.54

45,154.00

153,079.00

92,426.00

1999/00

2000/01

135

80

NA

NA

105,940.00

69,928.00

Sub-total 654 NA 466,527.00

Note: * Sanctioned units are number of units or sectors/functional areas allotted or planned for production/utilization of FDI by TNCs. ** Tk.1 million is equivalent to approximately U.S. $18,000. NA = Not available.

Source: Board of Investment (BOI), Government of Bangladesh, 2001. Also see

Reza, 1995.

FDI by TNCs is a major catalyst for the industrial growth of

Bangladesh. About 205 TNCs from more than 30 countries are making investments through FDI in different sectors and geographical areas of

Bangladesh. Data suggest that prior to independence, pharmaceutical and chemical industries, followed by petroleum companies, dominated the foreign capital inflow in Bangladesh in terms of attracting the bulk of

FDI (Reza, 1995, p. 30). But in post independent Bangladesh, the past scenario has been changed and the FDI scene is at present found to be dominated mainly by textiles (primarily ready-made garments), followed by chemicals and food processing industries. Between 1973 and 1994 these three industries together accounted for over three-fourths of the

365

366 ISLAM total FDI flowing into Bangladesh. The other industries that attracted

FDI flows are metals (3.49%), electrical goods (2.81%), paper and paper products (2.32%), leather and leather products (1.65%), pharmaceuticals

(1.21%) and plastic products (1.18%). Compared to the earlier trends,

TNCs now seem to be interested in making investments, not only import substituting, but also in a number of export oriented products like readymade garments, canning and preservation of fish, fruits and vegetables, shrimp culture and other food processing industries (Reza, 1995, p. 33).

From the start in 1978, the ready-made garments industry has emerged as a major export sector in Bangladesh. In 1992-93, garments alone accounted for 52% of total export earnings. Bangladesh now exports some 100 categories of garments to about 50 countries, including the

U.S., Germany, France, the U.K., Italy, the Netherlands, Canada,

Sweden, Belgium, and Norway. Bangladesh is now the seventh largest exporter to the U.S., ninth largest exporter to Canada, and the largest exporter of shirts and t-shirts to EC (Islam, 1994). Of 205 foreign firms in the country, 29 have invested in ready-made garments; 14 from Hong

Kong (presently China); six from South Korea; two each from Singapore and Netherlands; one each from India, the U.S., Switzerland,

Lichtenstein, and Japan (Islam, 1994). However, apart from the FDI inflow of TNCs, foreign investment in this country by TNCs have also taken other forms like technical collaboration, marketing/managerial collaboration, and licensing arrangement (Islam, 1994).

Factors Attracting TNC Participation in Host Country like

Bangladesh

TNC investments in Bangladesh are affected by several factors. One of the fundamental factors that affects the participation of TNCs in domestic economy is the market size. Bangladesh has limited natural resources, large population, low per capita income, low sectoral growth rate, and widespread poverty and unemployment. With a current per capita income of less than US $300 and a high degree of inequality characterizing its distribution groups, undoubtedly the size of the domestic market in Bangladesh is not considered to be very attractive for large-scale industrial investments, particularly by TNCs (Reza, 1995).

The rate of foreign investment in Bangladesh is lower than in other South

Asian countries including India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (U.S.

Department of State, 1998). Moreover, widespread administrative corruption, red tape, inefficiency, centralized authority in decisionmaking, etc. hinder the implementation of different developmental

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS programs that are also the stumbling blocks to the growth of TNCs in

Bangladesh. Despite all these difficulties, the number of TNCs and the amount of capital investment are increasing day by day, with some exceptions (Reza, 1995). So, naturally some questions arise: How are

TNCs increasing in Bangladesh? Why do TNCs invest more capital than in the past? What things attract TNCs to invest capital in Bangladesh and how are TNCs dependent on these things? If TNCs are dependent on

Bangladesh for resources, then what strategies do they adopt to balance the dependency? Answers to these questions lie in different factors.

First, the present political condition and liberalization of government’s industrial policies are encouraging TNCs to invest capital in Bangladesh. Presently, Bangladesh’s government has introduced broad-based reforms in the sectoral policies, i.e., progressive liberalization in trade and industrial policies, reduction in subsidies and market-oriented pricing policies for agricultural inputs and outputs, cuts in public expenditures to reduce budget deficits, privatization of government owned enterprises, implementation of reforms in the financial sector, increased efforts at domestic resource mobilization through tax reforms and reform in tax administration, strengthening the poverty-focused rural developmental effort and so forth, which are encouraging TNC investment in Bangladesh (Reza, 1995).

One of Bangladesh’s important resources that TNCs need is its labor market. According to a 1989 Labor Force Survey Report, the total labor force in the country stood at 50.7 million persons, of whom 29.7 millions were males and 21.0 millions females (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics,

1992; Reza, 1995). Due to the huge labor force, TNCs employ laborers from Bangladesh at low labor cost in comparison to their home countries.

This labor cost helps the TNCs to save their capital and further invest for production, which in turn brings more profits to them. From Marxist points of view, capitalists accumulate capital by exploiting the laborers/proletariats. The profits that capitalists make exploiting the laborers by offering lower pay is called surplus value that helps them accumulate more and more capital. This theory suggests that the rise of capitalism fully depends on the means of production i. e. the labor force.

So is the case of the TNCs in Bangladesh.

TNCs make profits through their investment in Bangladesh. On the other hand, Bangladesh depends on TNCs to bring about economic and social development through employment generation, technology transfer, increased tax revenue, increased exports and so on. TNCs use

367

368 ISLAM bargaining/negotiating strategy for balancing its dependency relationship

(Islam, 1994; Reza, 1995).

From these discussions, it is apparent that resource dependency theory is partly applied to TNCs operating in Bangladesh. An analysis of different factors reveals that Bangladesh is more dependent on TNCs than TNCs are dependent on Bangladesh. So, the resource dependency theory can be better applied to Bangladesh than to TNCs. Although presently TNCs are investing more capital in Bangladesh than in the past, it does not mean that TNCs are dependent on Bangladesh. Actually,

TNCs operating in Bangladesh are playing a monopolistic role. If TNCs break off relations with Bangladesh or do not invest in Bangladesh, then the economic growth of Bangladesh will be hampered. Developing countries like Bangladesh heavily depend on foreign investment for social and economic transformations of these countries (Al-Daeaj, et al.,

1999). TNCs also play a significant role in the Bangladesh government’s tax increases. Therefore, for a variety of reasons, it may be surmised that

Bangladesh is more dependent on TNCs than are TNCs on Bangladesh.

FACTORS THAT ARE NOT EXPLAINED BY RESOURCE

DEPENDENCY THEORY BUT HELP EXPLAIN THE BEHAVIOR OF

TNCs IN BANGLADESH

Resource dependency theory addresses the dependencies of one organization on the other organization. This theory gives more emphasis on how dependent an organization is and how the dependent organization can balance the interdependence by adopting prescribed strategies of the theory. One of the important factors of any organization is the vision and strength of making a cost-benefit analysis of that organization. By applying “resource dependency theory,” the performance of TNCs in

Bangladesh cannot be evaluated. In fact, the performance of any organization is evaluated by assessing the skills, abilities, traits and performances of the employees and analyzing the costs and benefits of the organization (Lecraw & Morrison, 1991; Oliver, 1990).

Needless to say, human beings are guided by their social, cultural and religious beliefs, values and norms. TNCs possess both positive and negative socio-cultural impacts for Bangladesh. On the positive side,

TNCs in Bangladesh sometimes undertake some social welfare projects— make donations to charitable organizations, sponsor games and sports and help promote cultural activities (Reza, 1995). On the other

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS hand, TNCs are seen as generating social tension by introducing differentiated pay structure between local and TNC enterprises. TNCs often hurt the feelings of the local people by not supporting their social, cultural and religious norms, values and beliefs (Reza, 1995; Al-Daeaj, et al., 1999; Lawler & Bae, 1998). For instance, Bata shoes allegedly violated the religious sentiment of the people of Bangladesh by introducing a new design (Reza, 1995). This behavior of the TNCs cannot be explained by resource dependency theory. It needs further explanations.

Resource dependency theory promotes balancing interdependency, but this theory ignores the repercussions that emerge when one organization eliminates its dependency on another organization.

However, it has been observed that a TNC breaking off negotiation or removing its operations from a host country like Bangladesh, has little effect on its other relationships. But if a host country like Bangladesh forces a TNC to terminate its operations in the HC, serious repercussions are likely to occur in its relationships with other TNCs or with the governments where the TNC is based (Lecraw & Morrison, 1991).

Why does it happen? Why is the TNC less dependent than the HC on the relationship? Unfortunately, answers to these questions are not fully addressed by resource dependency theory.

Data suggest that the large part of foreign investment in Bangladesh which is highly dependent on import has some adverse effects, including the following: the greater the extent of reliance on imports for production, the less the industry is linked with the local economy. In other words, the greater the direct foreign exchange cost (because of import dependence), the lesser will be the growth and spread effects of the investment. Second, the greater the reliance on imports, the larger becomes the scope for transfer pricing for firms controlled by foreign investors. Again, for firms that are locally controlled but technologically dependent on foreign firms, import dependence leads to a tying of imports to high cost sources (Islam, 1994; Reza, 1995). Despite these adverse effects, why Bangladesh encourages foreign investment in the country. Examining this complex issue helps understand the behavior of

TNCs in Bangladesh that cannot be explained by resource dependency theory.

369

370 ISLAM

CONCLUSIONS

Although resource dependency theory applies to TNCs operating in

Bangladesh, it does not explain all the factors that account for the behavior of TNCs. Analysis of the TNC investments reveals the fact that

TNCs’ participation in Bangladesh is mainly and most importantly affected by several factors, such as market size, economic growth, gross national product and political conditions of the country. Although the market size of Bangladesh is not considered to be very attractive for

TNC investments due to widespread poverty, unemployment and low per capita income, the country has improved as compared to the past decades after its independence. So, per capita income of the country with a population of about 130 million is increasing day by day. That is a significant reason for attracting TNCs in Bangladesh.

Since independence of Bangladesh in 1971, TNC investment through

FDI was deterred several times due to the political instability of the country. But because of a stable political atmosphere and liberalization procedures of the Industrial Policy 1991, TNC investment increased rapidly in 1993-1994. During the democratic governance of Begum

Khaleda Zia from 1991 to 1996, TNC investments by FDI increased 90 percent more than total sanctioned investments from 1971 to 1996.

Between mid-1996 and July 2001, total sanctioned investments by FDI in Bangladesh continued increasing. However, due to congenial political environment, about 205 TNCs of more than 30 countries are making investments through FDI in different sectors and geographical areas of the country (Islam, 1994; Reza, 1995, p. 126). Another reason for TNC investment in Bangladesh is that TNCs can employ laborers from

Bangladesh at low labor costs (Reza, 1995, p. 126; Islam, 1994).

In fact, due to technological backwardness and a relative lack of management skill and marketing experience, Bangladesh is more dependent on inflows of all types of foreign investments (Reza, 1995, p.

51). So, because of their control on capital and technology, TNCs possess stronger bargaining and political power that enables them to extract concessions and favorable terms from host governments like

Bangladesh, which may be denied to local firms (Reza, Rashid & Alam,

1987). Therefore, for a variety of reasons, resource dependency theory can better apply to Bangladesh than to TNCs operating in Bangladesh, because Bangladesh is more dependent on TNCs than TNCs are on

Bangladesh. That TNC investment during the last four years in

Bangladesh exceeds the investment of any time in the past does not mean

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS that TNCs are dependent on Bangladesh. Finally, it can be surmised that

TNCs are playing an oligopolistic role in the market economy of developing countries like Bangladesh.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is deeply indebted to Dr. Charles W. Washington, Dean,

School of Arts and Sciences, Clark Atlantic University for his valuable comments on the earlier draft of my manuscript.

NOTES

1.

Tk. (Abbreviation of Taka) is the Bangladeshi currency. Presently one U.S. dollar is equivalent to approximately 55 Taka (U.S.

$1=Tk.55). So, Bangladeshi Tk.1 million are equivalent to approximately U.S. $18,000.

2.

Sanctioned Units are the number of units/functional areas allotted or planned for production/use of FDI by TNCs.

REFERENCES

Al-Daeaj, H.S., Ebrahimi, B.P., Thibodeaux, M.S., & Nasif, E.G. (1999).

Perceptions of managers in Kuwait about multinational corporations’ role in changing that country’s business environment. International

Journal of Commerce and Management, 9 (3/4), 78-101.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (1992). Statistical Year Book of

Bangladesh . Dhaka, Bangladesh: Author.

Barnet, R.J., & Muller, R.E. (1974). Global reach: The power of the multinational corporations . New York: Simon and Schuster.

Board of Investment. (2001). Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh . Dhaka, Bangladesh: Author.

Daft, R.L. (2001). Organization theory and design . Cincinnati, OH:

South-Western College Publishing.

Encarnation, D., and Vachani, S. (1985, September-October). Foreign ownership: When hosts change the rules. Harvard Business Review,

63 (5), 152-160.

371

372 ISLAM

Fagre, N., & Wells, L. (1992). Bargaining power of multinational and host governments. Journal of International Business Studies , 13 (2),

9-23.

Harrison, A. (1994). The role of Multinationals in economic development: The Benefits of FDI. Columbia Journal of World

Business , 29 (4), 6-11.

Hellriegel, D, Slocum, Jr., J.W., & Woodman, R.W. (1998).

Organizational behavior . Cincinnati, Ohio: South Western College

Publishing, An International Thompson Publishing Group.

Islam, S. (1994). Foreign investment effects on balance payments: A

Bangladesh case study. Asian Survey , 34 (4), 343-354.

Kumar, K. (Ed.). (1980). Transnational enterprise: Their impact on third world societies and cultures . Boulder: Westview.

Lall, S., & Streeten, P. (1990). Foreign investment, transnational, and developing countries . London: Macmillan Press.

Lawler, J.H., & Bae, J. (1998). Overt employment discrimination by multinational firms: Cultural and economic influences in a developing country. Industrial Relations , 37 (2), 126-152.

Lecraw, D.J., & Morrison, A.J. (1991, September). Transnational corporation-host country relations: A framework for analysis. Essays in International Business, 9, 1-50.

Mahini, A. (1988). Making decisions in multinational corporations:

Managing relations with sovereign governments . New York: John

Willey and Sons.

Meleka, A.A. (1985). The changing role of multinational corporations.

Management International Review , 25, 36-45.

Newman, W.H. (1979, Summer). Adapting transnational corporate management to national interests. Columbia Journal of World

Business , 82-88.

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of interorganizational relations:

Integration and future directions. Academy of Management Review,

11 (2), 241-265.

Pan, Y., & Li, X. (2000). Joint venture formation of very large multinational firms. Journal of Business Studies , 31 (1), 179-189.

TRANSNATIONAL CORPORATION-BANGLADESH RELATIONS

Patel, S.J. (1974). The technological dependence of developing countries. The Journal of Modern African Studies , 12 , 1-17.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective . New York:

Harper and Row.

Pugh, D.S., & Hickson, D.J. (1997). Writers on organizations . Thousand

Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Rashid, S. (1993, March). The political environment and foreign direct investment decisions: The case of Sudan. Midwest Review of

International Business Research, 7 , 52-60.

Reiffers, J.L. (1982). Transnational corporations and endogenous development: Effects on culture, communication, education, and science and technology . Paris: UNESCO.

Reza, S. (1995). Transnational corporation in Bangladesh: Still at bay?

Dhaka, Bangladesh: University Press Limited.

Reza, S., Rashid. A., & Alam, M. (1987). Private foreign investment in

Bangladesh . Dhaka, Bangladesh: University Press Limited.

Ulrich, D., & Barney, J.B. (1984). Perspectives in organizations:

Resource dependence, efficiency, and population. Academy of

Management Review , 9 , 471-481.

U. S. Department of States, Bureau of South Asian Affairs. (1998, June).

Background note: Bangladesh . Washington, DC: Author.

373