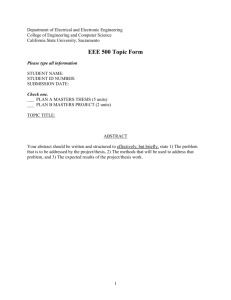

Theoretical Framework

advertisement