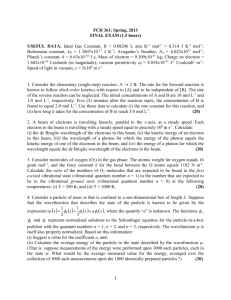

PHYSICS 495: QUANTUM MECHANICS & OPERATOR THEORY

advertisement

QUANTUM MECHANICS & OPERATOR THEORY

Dr. John Varriano

References:

Eisberg & Resnick, Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (2nd ed.),

Wiley, 1985.

Gasiorowicz, Quantum Physics (2nd ed.), Wiley & Sons, 1996.

Cohen-Tannoudji, Diu, & Laloe, Quantum Mechanics (Vols. 1 & 2), Wiley & Sons, 1977.

Martin, Basic Quantum Mechanics, Oxford Univ. Press, 1981.

Outline:

1. Review

A. Time-Dependent Schroedinger Equation

B. Wavefunctions

C. Time-Independent Schroedinger Equation

D. Example: Infinite Square Well

2. Operator Theory & Dirac Notation

A. State Vectors

B. Observables & Operators

C. Wavefunctions & Schroedinger Equation

3. Simple Harmonic Oscillator

4. Angular Momentum

5. Spin

6. Time-Independent Perturbation Theory

A. Introduction

B. Nondegenerate State Perturbation

C. Almost Harmonic Oscillator

D. Stark Effect for Ground State Hydrogen Atom

E. Degenerate State Perturbation

F. Stark Effect for Excited Hydrogen Atom

7. Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory

8. Variational Method

2

1. Review

NOTES:

A. Schroedinger Equation

Time-Dependent Schroedinger Equation

Let us begin by stating the one-dimensional time-dependent Schroedinger equation:

2 2 ( x , t )

( x, t )

V ( x, t ) ( x, t ) i

2m

t

x 2

(1.1)

Recall that we derived this equation by combining the Law of Conservation of Energy with the

deBroglie postulates and the assumption that a free particle (a particle which has a constant potential

energy) can be described by a wavefunction that is harmonic (sinusoidal).

We can extend this equation to three dimensions by simply replacing the second partial derivative with

respect to x to the Laplacian ( 2 ), and writing the wavefunction and potential energy as functions of the

three spatial variables x,y,z which we symbolize by vector r . This gives the three-dimensional timedependent Schroedinger equation:

2 2

(r , t )

( r , t ) V ( r , t ) ( r , t ) i

2m

t

(1.2)

Operators

Examining (1.1) shows that it retains the form of the Conservation of Energy Law. The first term on

the right is associated with the kinetic energy, the next term with the potential energy, and the left side

term with the total energy. We view each term as an energy operator that operates on the wavefunction

(x,t). We can identify the operators as follows:

kinetic energy operator

potential energy operator

total energy operator

{K}

2 2

2m x 2

{V}=V

{H } i

(1.3)

(1.4)

t

(1.5)

Why use the symbol H for the total energy operator? Borrowing from classical mechanics, the total

energy operator is called the Hamiltonian of the system. In fact, we will refer to the total energy operator

as the Hamiltonian. Since the Hamiltonian is the sum of the kinetic and potential energy operators, we

can also write that

3

{H}

2 2

V

2m x 2

(1.6)

We can find other operators which operate on (x,t) that correspond to other physical quantities. For

example, since K p 2 2m , we can write

momentum squared operator

{ p 2 } 2

and

momentum operator

{ p} i

2

x 2

(1.7)

x

(1.8)

The position x can also be viewed as an operator. It simply multiplies (x,t) by the value of x, similar to

the how the potential energy operator simply multiplies (x,t) by the value of the potential energy.

Thus, we add

position operator

{x} = x

(1.9)

B. Wavefunctions

The standard interpretation of quantum mechanics is that all of the information that can be known

about the particle is derivable from the particle’s wavefunction. The way this information is obtained is

by using the probability density function which is the product of the wavefunction and its complex

conjugate. Recall that the probability of finding the particle in some small length is the probability

density times that length, i.e.

probability of finding the particle in some interval dx * ( x, t ) ( x, t ) ( x, t )

2

(1.10)

To measure a physical quantity of the motion, such as position, often the best we can do is to find the

average value of the quantity. Recall, for instance, that the average position in one dimension is given

by

x

* xdx

(1.11)

The first homework problem has you write down the expressions for other physical quantities.

4

C. Time-Independent Schroedinger Equation

Let’s keep working in one dimension and write down the one-dimensional time-independent

Schroedinger equation:

2 2 ( x)

V ( x) ( x) E ( x)

2m x 2

(1.12)

How does one get this equation? Recall that you can derive it from the time-dependent equation (1.1) by

making the following two assumptions:

1) the potential energy doesn’t change with time, V(x,t) = V(x)

2) the wavefunction is separable and can be expressed as the product of a spatial function and a

temporal function, ( x , t ) ( x )(t )

By making these substitutions into the time-dependent equation, the time-independent equation results,

and we also learn that (t ) e

i

E

t

which means that the wavefunction is harmonic in time.

Using the Hamiltonian operator notation allows us to write (1.12) as

{H} E

(1.13)

Recall that this equation is an eigenvalue equation. The Hamiltonian operates on the wavefunction and

gives back the wavefunction times a number (the energy). We call the wavefunction an eigenfunction or

eigenstate of the Hamiltonian operator and the energy an eigenvalue.

D. Example: Infinite Square Well

We have already analyzed a particle in a one-dimensional infinite square well. Homework problems

[1.2] and [1.3] review the important details of the system. The infinite square well serves as a good

example of how the time-independent Schroedinger equation is used to solve a quantum mechanical

system.

We take the potential energy to be zero inside the well which extends from x=-a/2 to x=+a/2 and to be

infinite outside this region. The well is centered on x=0.

5

PROBLEMS:

[1.1]

Consider a particle moving in one-dimension characterized by the wavefunction (x,t). Write

expressions for the following quantities:

(a) probability of finding particle in some small interval dx

(b) probability of finding particle between x=a and x=b

(c) the normalization condition for the wavefunction

(d) average value of its position

(e) average value of the square of its position

(f) average value of its momentum

(g) average value of the square of its momentum

(h) average value of its potential energy

(i) average value of its kinetic energy

(j) average value of its total energy

(k) uncertainty in its position

(l) uncertainty in its momentum

[1.2]

Consider a particle in a 1-D infinite square well of width a.

(a) Verify that (x) = Ansinknx + Bncosknx satisfies Schroedinger’s equation for the region inside the

well. Write down the expression for the energy.

(b) Apply the boundary conditions at x=-a/2 and x=+a/2. Show that you obtain the following two

classes of solutions:

n 1,3,5,...

Bn cos k n x

n ( x)

n 2,4,6,...

An sin k n x

(c) Show that the particle’s energy is

E n2

22

2ma 2

[1.3]

Consider the ground state of the particle in Problem 1.2.

(a) Sketch the well and the wavefunction.

(b) Sketch the well and the probability density

(c) Show that the average position of the particle is x=0

(d) Show that the average momentum of the particle is zero.

(e) Show that the normalization constant is B1 2 a .

. 0.57

(f) Show that xp 018