Crustal motion and block behaviour in SE-Asia from GPS

advertisement

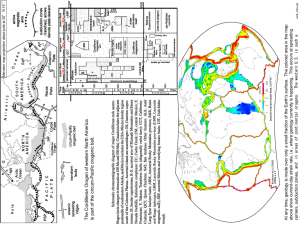

Crustal motion and block behaviour in SE-Asia from GPS measurements Gero Michel*, Christoph Reigber*, Matthias Becker†, Herman Seeger†, Wim Simons‡, Boudewijn Ambrosius‡, Christophe Vigny§, Nicolas ChamotRooke§, X. Le Pichon§, Peter Morgan||, Saskia Matheussen|| * GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Germany †Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ‡Delft Institute for Earth-Oriented Space Research, Delft, Netherlands §École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France ||University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia Current deformation of SE-Asia has been discussed controversially. The eastern margin of Eurasia, from North China to Indonesia, has been successively considered as rigidly attached to Eurasia1, continuously deforming2, or formed by a mosaic of blocks deforming mainly at their boundaries3-6. Modern space geodetic tools can resolve these controversies by quantifying crustal deformation. Here we show results acquired using GPS data taken over a large part of SE-Asia, that indicate that Sundaland, i.e. Indochina along with the western and central part of Indonesia, constitutes a stable tectonic block moving approximately east with respect to Eurasia at a velocity of 12±3 mm yr1. With respect to India and Australia this block moves due south. Significant motion has not been detected along the northern boundary to S. China i.e. along the Red River Fault, whereas nearly 50 mm yr-1 of right lateral motion has to be accommodated between India and Sundaland in the Andaman-Myanmar region. Cenozoic deformation in SE-Asia has been related to the ongoing convergence of the Indian, Australian, Pacific and Philippine Sea plates towards Eurasia (Fig. 1). Recent GPS results indicate that North and South China are decoupled from Eurasia7,8 and move eastward with a velocity of 5 to 11 mm yr– 1 . Further south, previous geodetic results over Sundaland (i.e. Indochina, the Sunda Shelf, Borneo, Sumatra, and Java) suffered from ill-defined global reference system9, network restricted to a small region10,11, or concentrated on seismically active boundaries10,12. Repeated measurements were made of a GPS network extending over an area of 4000 by 4000 km (Fig. 1), covering Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. This geodynamics of S and SE-Asia (GEODYSSEA) network was measured in 1994, 1996, and 1998. Data were analysed independently by 5 different groups and combined to reach the final solution mapped into ITRF9713 (see methods section). Strain and rotation rates obtained by Delauney triangulation (Fig. 2a-b) show a remarkably simple pattern: high straining regions are restricted to the Philippine Mobile Belt to the east and the Sumatra shearing zone to the west, both areas having opposite sense of rotation. The central part of the network covering Sundaland shows no deformation and no rotation, and accordingly displays a coherent velocity field. We chose a subset of 10 stations defined by small baseline variations (<4 mm yr-1) and small interstation strains (<2x10-8 yr-1) to define a “rigid” Sundaland platelet. Motion of these sites can be modelled to within 3 mm yr-1 with a single Euler vector (56.0°S, 77.3°E, - 0.339°Myr-1 in ITRF97) significantly distinct from the NNR-NUVEL1A frame Eurasian vector14. Both vectors were combined to derive the Sundaland/Eurasia vector (63.6°S, 107.4°E, - 0.112°Myr-1). To further explore the accuracy of the obtained Sundaland/Eurasia pole, we also computed Euler vectors for each individual solution obtained by the four analysis groups (Fig. 3). Clearly the longitudinal position of the pole is well constrained whereas the latitudinal position is not. These independent solutions place constraints on the accuracy of our combined solution and suggest that although the average east component of Sundaland motion with respect to Eurasia is distinct at 10 to 13 mm yr-1 (Fig. 3), a small and systematic variation of this component with latitude and an associated small north component shift cannot be ruled out. This implies two interpretations: Sundaland platelet escapes due east with respect to Eurasia at an average rate of 12±3 mm yr1, or Sundaland rotates clockwise with respect to Eurasia at a velocity increasing from 10 mm yr-1 in the south to 15 mm yr-1 in the north. Differences between the extreme solutions represent the uncertainty of our solution in terms of GPS measurements reduction and reference frame realisation in this area of the world, where ionospheric noise is high and fiducial stations are scarce. Moreover part of these discrepancies originate from transient effects, not yet understood, indicated by the time series in the station velocities at BALI and BUTU. Velocities of these stations are lower (1994-1996) and higher (1996-1998) than predicted by the other 8 stations of the Sundaland block. This new geodetic solution demonstrates that a large piece of the eastern Eurasian margin behaves to first order as a single block, as suggested previously by the results of the two first rounds of GEODYSSEA measurements 9,15,16. To the north, relationship of this Sunda block with the adjacent and previously defined South China block is still to be established, but in any case differential motion is small and at the detection limit of our data. Predicted rates on their assumed boundary, the Red River Fault, are at the 0 to 5 mm yr-1 level. To the south, the Sundaland block is bounded by the Great Sumatran Fault and the Sunda Arc. Relative motion between Sundaland and Australia is approximately north suggesting similar eastward component of motion for both plates along this boundary. The apparent difference between the NUVEL1A convergence direction and earthquake slip directions discussed in the literature17 thus appears to have been resolved. Convergence rates between Australia and Sundaland reach values between 66 and 72 mm yr-1. Relative velocities of sites on the fore-arc sliver on Sumatra with respect to Sundaland suggest strike-slip motion of between 20 and 30 mm yr-1 along the Great Sumatran Fault. Along the Australian and/or Indian plate interface with Sundaland, intraplate shortening and/or high rates of elastic strain accumulation at Sumatra is in contrast to localised deformation on Java and Bali where sites appear to be significantly less affected by elastic loading and follow the motion of “stable” Sundaland. Along the Banda Arc, collision occurs between the Australian continental lithosphere and a complex blocks assemblage in the area of the triple junction between the Pacific/Philippine Sea plate, the Australian plate and Sundaland. Here deformation is transferred from the Timor Trench to the north where it is concentrated on the back-arc thrust system12 as well as influencing motion of sites within the Banda Sea and Sulawesi area. In this region, a large portion of the deformation is accommodated by small-scale block rotations at rates of up to 4° Myr-1. To the east, convergence between the Philippine Sea plate and Sundaland partitions within the complex Philippine Mobile Belt where transcurrent motion as well as highly distributed deformation and block behaviour18 have been observed. To the west, motion of India with respect to Sundaland is roughly north at a rate of 45 to 52 mm yr–1. Relative motion is accommodated by opening of the Andaman Sea, strike slip motion on the Sagaing fault system, oblique shortening along the Andaman and Burma subduction arc, and rotation about the eastern syntaxis of India. During the Tertiary19 the Sundaland region was divided into a small number of distinct provinces each with distinct boundaries and motion. The apparent change from this regime to one of relative homogeneity that accommodates the eastward component of the motion of the Indian and Australian plates is remarkable. One plausible explanation is the general change in the boundary conditions of E and SE Asia with the onset of subduction and subsequent roll-back along the Philippine trench in the late Miocene19. The alternative is that Sundaland eastern motion relates to eastward motion of India appearing about 8.5 to 10 Ma20, when the Indian equatorial zone of deformation was initiated and India plate was detached from Australia plate. In any case, this new evidence for a rather homogeneous motion of E and SE-Asia definitely rejects any model that includes either intense deformation within the blocks or large transcurrent displacements between them. Methods Data analysis GPS observations were conducted simultaneously at 42 stations and included data from the Australian Survey and Land Information Group (AUSLIG) and the International GPS Service for Geodynamics (IGS). Five analysis groups (BKG, DEOS, ENS, GFZ, and UC) computed daily station coordinate solutions for the individual campaign data sets. Each group used the latest version of one of four GPS software packages (i.e. BERNESE v4.0 21, EPOS v3.022, GAMIT v9.923, and GIPSY-OASIS II v2.524) and applied their favoured analysis strategy9,25. Processing included the following: fiducial-free network solutions, ionosphere-free linear combinations of GPS data, tropospheric modelling, and IGS antenna phase centre tables. Consequently this solution differs from earlier solutions9 by virtue of the additional epoch and the use of additional global IGS stations. Additionally precise GPS satellite orbits/clocks and corresponding earth rotation parameters from the IGS, GFZ, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and UC were applied. For the 1994 and 1996 campaigns these data were newly computed using the ITRF97 reference frame. The daily solutions of each group were combined into multi-day averaged solutions with the 3D-motion software26. These were then combined into averaged coordinate solutions for the individual campaigns that had formal errors about half that reported earlier 9. Accuracy The daily coordinate repeatabilities of the GEODYSSEA stations for each campaign range between 2.5 and 6.5 mm for the horizontal components and between 6 and 15 mm in height. The internal consistency of all contributing multi-day averaged group solutions is 2, 4, and 7 mm in the north, east and up components. A precise estimate of the horizontal station velocities was obtained by mapping each campaign solution into the ITRF97 13 frame using 12 global IGS sites, with long and stable time series that operated during each campaign. This was done using linear models for all stations not affected by nearby large earthquakes (i.e. Biak and Tomini in Indonesia). The 1-sigma quality of these models was 2 mm yr-1 in north-south and 3 mm yr-1 in the east-west direction. Transient effects Abundant large earthquakes suggest that transient seismic deformation processes may have significantly influenced some of the observed site motions15,18. Seismotectonic methods, together with dislocation modelling were therefore applied to estimate the influence of coseismic deformation release and interseismic elastic loading on the site motions27. Results indicate that apart from the eastern perimeter of the study area, where the transition zone between the adjoining plates and Sundaland extends for up to 1000 km, and the fore-arc sliver at Sumatra, the sites appear to be almost unaffected by seismic elastic loading and release phenomena. Acknowledgements References 1. Tregoning, P. et al. First geodetic measurement of convergence across the Java Trench. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 2135-2138 (1994). 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. Kreemer, C., Holt, W.E., Goes, S. & Govers, R. Active deformation in eastern Indonesia and the Philippines from GPS and seismicity data. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 663-680 (2000). Peltzer, G. & Saucier, F. Present-day kinematics of Asia derived from geologic fault rates. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 27943-27956 (1996). Molnar, P. & Tapponier, P. Cenozoic tectonics of Asia: Effects of continental collision. Science 189, 419-426 (1975). Avouac, J-P. & Tapponier, P. Kinematic model of active deformation in central Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 20, 895-898 (1993). Houseman, G. & England, P. Crustal thickening versus lateral expulsion in the India-Asian continental collision. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 12233-12249 (1993). Heki, K. et al. The Amurian Plate motion and current plate kinematics in eastern Asia. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 29147-29155 (1999). Shen, Z. et al. Contemporary crustal deformation in east Asia constrained by Global Positioning System measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 5721-5734 (2000). Simons, W. J. F. et al. Plate Motions in South East Asia: results of the GEODYSSEA Project. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 2081-2084 (1999) Puntodewo, S. S. et al. GPS measurements of crustal deformation within the Pacific-Australia plate boundary zone in Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Tectonophys 237, 141-153 (1994). Yu S.-B., Kuo, L-C., Punongbayan, S., & Ramos, E.G. GPS observation of crustal deformation in the Taiwan.Luzon region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 923-926 (1999). Genrich J. et al. Accretion of the southern Banda arc to the Australian plate margin determined by Global Positioning System measurements. Tectonics 15, 288-295 (1996). Boucher, C., Altamimi, Z. & Sillard, P. The 1997 International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF97). IERS Technical note 27, Observatoire de Paris (1999). De Mets, C., R. Gordon R.G., Argus D.F., & Stein, S. Effects of recent revisions to the geomagnetic reversal time scale on estimates of current plate motions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 2191-2194 (1994). Wilson, P. J. et al. The GEODYSSEA project: An investigation of the geology and geodynamics of South and South-East Asia. EOS 79, 545, 548-549 (1998). Chamot-Rooke, N. & Le Pichon, X. GPS determined eastward Sundaland motion with respect to Eurasia confirmed by earthquakes slip vectors at Sunda and Philippine trenches. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 173 (4), 439-455 (1999). McCaffrey, P. Slip vectors and stretching of the Sumatran fore arc. Geology 19, 881-884 (1991). Rangin, C. et al. Plate convergence measured by GPS across the Sundaland/Philippine Sea Plate deformation boundary: Philippines and eastern Indonesia. Geophys. J. Int. 139, 296-316 (1999). Hall, R. Reconstructing Cenozoic SE Asia. in Tectonic Evolution of SE Asia (eds. Hall, R. & Blundell, D. J.), Geol. Soc. Spec. Pub. 106, 153-184 (1996). Royer, J.-Y., Gordon, R.G., DeMets, C. & Vogt, P.R. New limits on the motion between India and Australia since chron 5 (11 Ma) and implications for lithospheric deformation in the Equatorial Indian Ocean. Geophys. J. Int. 129, 41-74 (1997). Rothacher, M. & Mervart, L. Bernese GPS Software Version 4.0. Astronomical Institute, University of Bern, Bern (1996). Angermann, D., Baustert, G., Galas R., & Zhu, Z.H. EPOS.P.V3 (earth parameter & orbit system), Software user manual for processing of GPS networks, STR. 97/14, GFZ Potsdam (1997). King, R. W., & Bock, Y. in Documentation for the GAMIT GPS software analysis version 9.9 (Mass. Inst. of Technol., Cambridge, 1999). Blewitt, G., et al. GPS geodesy with centimeter accuracy. in Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences (eds E. Groten, E. & Strauss, R.) (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1998). Angermann, D. The datum definition of the GEODYSSEA network. in The Geodynamics of S and SE Asia (GEODYSSEA) Project (eds Wilson, P. & Michel G.W.) STR 98/14, 113-119 (Potsdam, 1998). Noomen, R., Ambrosius, B.A.C., & Wakker, K.F. Crustal motions in the Mediterranean region determined from laser ranging to LAGEOS. Contributions of Space Geodesy to Geodynamics. 23, 331-346 (1993). 27. Michel, G. W., Becker, M., Angermann, D., Reigber, C., & Reinhart, E. Crustal motion in E and SE-Asia from GPS measurements. Earth, Planets and Space (2000) in press. Figure legends Figure 1 SE Asian GPS velocity vectors in the Eurasian reference frame. Grey arrows: permanent stations from IGS and AUSLIG, white and red (stable Sundaland) arrows: GEODYSSEA. Inset map: triple junction densification area (vectors relative to Sundaland). Error ellipses are 99% confidence level. White circles: seismicity from the CMT catalog (1977 to present). Black lines show main SE Asian faults. Figure 2 Strain and rotation rates in Delauney triangles within the GEODYSSEA network. a, Strain rates, horizontal principle axis of the deformation tensor (red for compression and blue for extension). b, Rotation rates (red wedges for clockwise rotations and blue for anti-clockwise rotations) with associated uncertainties (grey wedges). Green dots show rigid Sundaland sites. Figure 3 Sundaland motion with respect to Eurasia. a, Positions of plate rotation poles with associated uncertainty ellipses (99% confidence): Eurasia in NNR-NUVEL-1A (black star), Sundaland in ITRF97 (open stars), and Sundaland relative to NUVEL-1A Eurasia (open dots). Group solutions GFZ (orange), ENS (green), DEOS (yellow) and UC (violet), and combined solution (grey) are shown. Poles are connected by corresponding great circles (dashed lines). b, Sundaland stations east velocity sorted by latitude. For each of the individual solutions and the combined solution, we show actual values (symbols) and trends (solid lines) predicted by the various Sundaland/Eurasia poles (same color coding as a). c, Sundaland stations north velocity sorted by latitude.