Improving Hydropower Project Decision Making

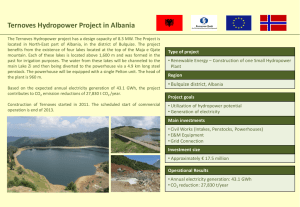

advertisement