“From Arithmetic to Algebra and Beyond:

advertisement

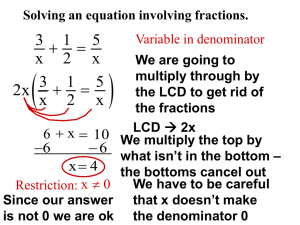

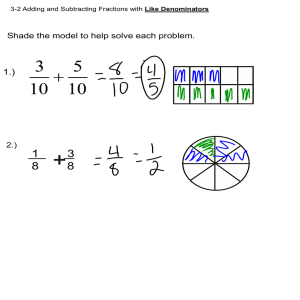

“From Arithmetic to Algebra and Beyond: ‘The Jealousy Method’ for Addition and Subtraction of Fractions” by H. Paul McGuire San Diego Miramar College Email: phyl.hil@gmail.com Phone: (858) 578-3421 Do you have students who flunk tests on Least Common Multiple? …who don’t make the transition from learning LCM to using LCM as LCD? …or who confuse what to do in multiplication and division with what to do in addition and subtraction of fractions? Don’t worry, skip LCM and go straight to LCD. LCM has little practical use (especially not in college mathematics) other than to get LCD and there’s another way to get LCD which is so unusual that it helps students distinguish addition and subtraction from multiplication and division. Furthermore this method focuses on the meaning behind the words Least Common Denominator and generalizes well to reveal the true nature of algebraic thinking. I developed this method while teaching all three middle school grades in the heart of the barrios of East Los Angeles. Desperate to rouse students’ interest in math and realizing they would play a favorite song over and over, I wrote the adjoining poem and set it to rap and pop music. I never claim that this is the only or best way to explain LCD, but students who do not understand the typical method of teaching and even many who do, can profit from “The Jealousy Method for Addition and Subtraction of Both Arithmetic and Algebraic Fractions”. Leaping straight into Least Common Denominator, we focus on the names (denominators) of the fractions being added. We don’t add dogs to horses. If we have 5 dogs and 3 dogs, we get 8 dogs. But 3 dogs plus 2 horses can’t be added. They remain just 3 dogs and 2 horses. Thus 5/7 + 3/7, like 5 dogs and 3 dogs, give 8/7. So for addition we need denominators to be the same. Subtraction is nothing more than adding a negative. So for both addition and subtraction we must have the same denominators. Another word for “same” is “common”. Now what’s this about a LEAST common denominator? Well, in numeric denominators and especially later in algebraic expressions, smaller is better. So we want our denominators to be the smallest (least) possible. Getting the prime factors of the denominators gets us down to their nitty-gritty, minimum constituents. Once there, we can compare the factors of one fraction with those of another to get the LCD. Here’s how. Say that student Joe notes that he has factors of 2 and 3 in the denominator of his fraction 5/6. Perhaps he looks at his friend Pete who has factors of 3 and 3 in the denominator of his fraction 2/9. Now if Joe has a jealous or envious streak, he might say, “Hey, I have factors of 2 and 3 but Pete has a PAIR of 3’s. I want another 3 for my denominator.” One of the beautiful things about mathematics is that we can satisfy any fraction’s jealousy without costing ourselves or the taxpayers anything. By the multiplicative identity law (a.k.a., multiplication property of 1) we can multiply top and bottom of a fraction by the same thing and still have identically the same original fraction. 1 So if Joe is jealous about Pete’s fraction having a 3, which Joe doesn’t have, we can multiply both numerator and denominator of Joe’s fraction by a 3 since 3/3 is one of the infinite number of forms of the multiplicative identity element, 1. Now Joe’s 5/6 looks like (5/6)(3/3) or 15/18. That is, he has 2 factors of 3 as well as a 2 in his denominator. His jealousy is assuaged! But Joe’s friend Pete is similarly afflicted by the most beautiful jealousy in the world (one which doesn’t harm anyone or any relationship). Pete sees that Joe’s denominator has a factor of 2. “I want a 2 too,” Pete pouts. Wonderful mathematics can comply easily. We multiply his 2/9 by 2/2 changing the looks of 2/9 into 4/18, but not its value. Pete is proud of his larger look. 4/18 impresses the girls more than 2/9 did! This transformation makes Joe and Pete better buddies than ever. Since they both have the same denominators, one can add to or subtract from the other: “Joe minus Pete” is 5/6 – 2/9 or 15/18 – 4/18 = (15-4)/18 which gives 11/18. Or “Joe plus Pete” = 15/18 + 4/18 = (15+4)/18=19/18. Of course all of this gets a bit heavy for Joe and Pete so I try to make it a bit more palatable with a “rapable” poem. You say my friends that Jealousy is bad? Well I’m tellin’ you it’s the latest fad. For any two fractions to add or subtract, “The Jealousy Method” is powerfully packed. First prime factorize the denominators. This will help us out a little later. Prime factorization too complicated? Don’t get weak; 2 Prime factorization is always unique. Next the denominators look at each other, Get just as jealous as a sister and a brother Each one wants what the other one’s got, But what you give to the bottom must go to the top. The reason for that’s got a terrible name Which you don’t need to know to play the game. [But if you really want to know, it’s the Multiplicative Identity Law which says that “one” times anything gives that same anything.] Now the denominators are common, The same for each one. Just one step more And we’re soon to be done. Write the denominator just once; [Why write it just once? Because it’s “common,” the same for each numerator. If Joe and Pete have a common hat, it belongs to both of them.] Write the denominator just once, Add ‘em up on top. Now there’s the answer So you can finally stop. If that’s not the most beautiful jealousy in the world, At least it may help some boy and some girl. 3 Younger (less inhibited) students and/or teachers can get into singing or rapping the poem. Some of my students and I have made a music video of sorts which I lend to students who miss class or who want to share the method with parents or siblings. Even though the example above is arithmetic, “The Jealousy Method” generalizes well for students of algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. This is the essence of algebraic thinking: Algebra is generalization of arithmetic. So we need to teach arithmetic in a way which generalizes easily to algebra and other courses. To add or subtract any fractions of whatever type, we prime factorize denominators then let them be jealous of each other. The Jealousy Method is an elephant gun (a generalizer) that dispatches both the simplest and the largest fractions. As the poem says, “For any two fractions to add or subtract, The Jealousy Method is powerfully packed.” Admittedly this approach is mathematically equivalent to what good mathematical practice has always dictated, but it emphasizes dissection of and then understanding of the term “Least Common Denominator”. Prime factorization provides leastness and jealousy leads to commonality. Furthermore this presentation is in terms of something every student recognizes as being part of life: jealousy. Let us bring math to life by bringing life to math for our students. 4