In order to measure economic dynamism in economy , an indicator

advertisement

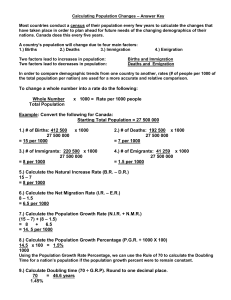

18th Roundtable on Business Survey Frames Beijing, China October 18 – 22, 2004 Session 8: Enterprise Demography Patrizia Cella and Caterina Viviano, ISTAT, Italy Register entries/exits and demographic flows: some comparisons for statistical aggregates 1- Introduction In order to respond to the need of indicators on Business Demography (BD) at national and international level, the work carried out from the Eurostat project launched in 2000 together with the NSIs is already well known. To achieve the highest possible comparability of data, the main objective of this project is to develop an harmonised methodology to identify those demographic aggregates having the major priority (births, deaths, survival)1. The identification process of real enterprise births and deaths is based on the application of a complex and expensive procedure; it is build up on a set of automated and manual steps aiming to eliminate (that is to identify) non real components from the set of entries and exits units into the BR2. The use of registration and deregistration of units into the BR does not allow to have comparable statistics among Countries for different reasons (different units, different national legal framework etc.). But at national level, which are the differences in the production of demographic statistics using registration and deregistration instead of identifying the real births and deaths by the harmonised methodology? Italy has implemented this common methodology and started to produce data on enterprise demography in official way with reference to years 1998-2002. This paper aims to verify whether the application of this methodology changes demographic information provided to users with regards to dynamics of the economic system. Raw data on entries/exits in/from the BR and “real” data, obtained after the application of methodology, are compared and the impact of using such different subsets is measured through calculation of some indicators. These indicators concern enterprise births rates, average size of enterprises, gross and net turnover rates in terms of enterprises and persons employed. Results confirm the usefulness of the methodology for identifying different demographic components; moreover they give some elements to reflect on how to allocate resources and in which steps of the process to address efforts. 2 - Business Demography methodology – summary of the main steps of the identification process Users that want to know how many new enterprises have been created in a specific year, they usually compare populations of active enterprises referred to two adjacent years (t, t-1). Once a year the BR department produces a frozen file of active enterprises that internal users can access at micro level. This file contains in addition to the identification and structural variables even 1 Business Demography-Recommendations Manual. ‘Business Demography statistics in the EU –first results and way forward’, paper presented by Eurostat at Session 7, 17th roundtable on BSF, Rome 2003 2 See definitions of enterprise birth and enterprise death, European Commission Regulation N.2700/98 1 demographic information such as the state of activity of each unit 3. A registration unit into the BR is tested according to the methodology determining whether it is active or not active on the basis of some signals of activity (presence of turnover or employment); on the basis of this information entries can be identified in a population of active units. A formalisation of the demographic flow is given by the following equation : P(t ) P(t 1) E (t ) U (t 1) = A E (t ) where: P (t ) =population of active units in year t P(t 1) = population of active units in year (t-1) E (t ) = entries in year t U (t 1) = exits from year t-1 A = active units both in year t and t-1 Entries (and exits) are affected only by the structure of signals of activity (coming from the integration of administrative files) and by the methodology of attribution of the state of activity4. The identification process, as described by the BD methodology, is carried out for the two demographic components separately. With regards to the new enterprises (entries) some steps are followed to reach the final result i.e. the real enterprise births (data on enterprise deaths is produced with a “mirror” process). We summarise all the process into 3 steps each determining a relative subset of data on which analyses are carried out. STEP 1 -The first step consists in comparing 3 subsequent populations of active enterprises (Pt, Pt-1 e Pt-2 ). This operation allows to eliminate reactivated units. The resulting equation becomes: P A [ E1 Er ] where: E1 =units not active both in year t-2 and t-1, and active in t E r =reactivations: units active both in year t-2 and t, but not active in t-1 E1 is the subset of entries cleaned from reactivations. Since reactivations represent a small percentage of the overall entries and their distribution does not influence the economic activities structure, E1 constitutes the first subset of data to be analysed for following comparisons. STEP 2 - Mergers and other events of structural changes involving enterprises’ re-organisation cause creations of new units into the register. Exclusion of such events (break-ups, split-offs, mergers and take-overs) from the E1 is possible because of the availability of a data set of integrated information coming from administrative and statistical sources. These events affect mainly larger enterprises which data are monitored from profiling activities carried out by skilled staff working at the BR maintenance. The link between firms involved in the events is recognised. In the previous equation E1 is split into two components according to the following formula: P A [( E2 Eev ) Er ] ‘The use of administrative sources to model the activity status of enterprises’, paper presented at Session 4, 16th roundtable on BSF, Lisbon 2002 4 For larger enterprises the status of activity is identified by profiling activities. 3 2 where: E2 = entries not due to events of structural changes E ev = creations due to events of structural changes E2 represents the second subset of data to be analysed. STEP 3 – The further step consists in identifying and excluding those false entries because continuing the activity of some other units. Continuity rules are assigned through a (automatic) Record linkage process5, that matches units according to economic activity and location, name and location, economic activity and name, and the use of other nationally available information 6. This step contains also the results of manual controls for large enterprise births, that is those births with more than 20 employees. E2 component is split as follows: P A [( E3 Econt ) Eev Er ] where: E 3 = Real births Econt =creations due to the continuity rules application The E 3 component identifies the subset of real enterprise births. On the basis of the above formalisations, E1 (entries of units into the population of active enterprises without reactivations), E2 (entries cleaned by events) and E3 (real births, i.e. entries cleaned by events and for the application of continuity rules) represent the three subsets of data that will constitute the basis to calculate indicators. Analysis will focus on the impact that such indicators have on the economic sector distribution. In year 2002 the number of units in the three data sets totalled 352, 350 and 295 thousands respectively. 3 – Some results from the comparisons of demographic indicators. 3.1 – Enterprise births rates The three enterprise birth rates distributions, each one calculated on the basis of the three subsets of data (E1, E2 and E3), show not a significant difference (Box1). From displayed data the 3 distributions present similarities both in terms of variability, having very close interquartile range values (around 4.3 for every distribution), and in the distribution shape (skewness Fisher index is approximately 1.2). The statistical median is equal in distributions E1 and E2 (7.7), but it goes down of around 25% in the E3 highlighting an overall reduction in enterprise birth rates level for each sector (6.1). 5 A detailed description of the Record linkage procedure is presented in Annex to methodological report, Italy, first harmonised data collection, year 2002. 6 The Chamber of Commerce archive on links between partnerships and partners. 3 BOX-plot 1: Enterprise birth rates (%) for economic activity, year 2002 17.8 15.8 13.8 14.4 14.3 11.8 10.8 9.8 7.8 7.7 6.5 4.9 5.8 12.0 9.3 10.8 7.7 6.4 4.9 6.1 3.85.0 3.8 E1 E3 E2 Looking at the employment creation of new enterprises, the three distributions of birth rates in terms of number of persons employed show interesting differences, above all for some economic activities (Box2). BOX-plot 2: Enterprise birth rates (%) for economic activity in terms of persons employed, year 2002 8.2 8.9 6.2 8.1 5.9 4.2 4.0 2.2 2.4 1.2 4.7 2.5 1.4 0.3 0.2 E1 6.5 5.7 E2 1.8 0.21.0 E3 There is a change towards lower levels from distribution E1 versus E3; in fact range varies from 8.6 to 6.3 and median reduces from 4.0 to 1.8; variability is increasing in distribution E2 (the interquartile range amounts to 4.4) while it returns to a lower value in E3 (around 3.5). In detail, there are sectors that change position in the distribution moving from quartile Q3 to Q1: across industry this shift is shown by coke refined petroleum products and chemicals, transport equipment and energy; for the services by financial intermediation, insurance & pension funding. As expected birth rates in terms of enterprises reduce mainly because of the application of continuity rules while birth rates in terms of employment change mainly for the exclusion of events. These results are confirmed looking at the size of units. 4 Figure 1 – Average number of persons employed in population of active enterprises and enterprise births for E1, E2 and E3, year 2002 Total Services Trade Construction Industry 0,0 2,0 4,0 Pop E1 6,0 E2 8,0 10,0 E3 The average size of new enterprises is very small in all the main economic sectors; this is particularly evident when comparing the average size of new enterprises with the average size of active enterprises. Industry reports higher average sizes in comparison to the other sectors (Figure 1). Looking at distribution E1 and E2 industry sector shows the highest gap due to the greatest impact of events. 3.2 – Demographic turnover Both demographic indicators, births and deaths rates, give on the whole an indication of enterprise turnover that is a proxy for dynamism of economy. The gross turnover rate, obtained as the sum of the number of enterprise births and deaths divided by the population of active enterprises, is a measure of turbulence of a system of enterprises and an index of renewal of markets. Figure 2 - Enterprise gross turnover rate - year 2001 40,0 35,0 30,0 25,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 E1 E2 5 E3 total resea rc h other busin ess hotels transport aux. Tran sp ort post, teleco m. financi al int. aux. fin anc. real e state rentin g computer retail trade mineral meta ls mac hin ery el ectric al eq . transport eq . manu fact.o thers energy construc tio n sale,repai r wholesale tr ade pape r coke rubber wood mining food textile le ather 0,0 In year 2001 enterprise gross turnover rate, calculated on real enterprise births and deaths, amounts to 15% for the total. Across sectors, values range from 34.1% (post & telecommunications) to 8.9% (mining and quarrying) (Figure2, distribution E3). The three distributions are very similar except for some economic activities. In fact the energy and financial intermediation sectors present differences in level and trend of gross turnover rate due to the impact of events (it is evident by comparing E1 with E2 distribution); instead for hotels and computer activities the reduction of rates is to be attributed mainly to the continuity rules assignment effect (it is evident by comparing E1 with E3 distribution). Figure 3 - Employment gross turnover rate - year 2001 20,0 18,0 16,0 14,0 12,0 10,0 8,0 6,0 4,0 2,0 E1 E2 total resea rc h other busin ess hotels transport aux. Tran sp ort post, teleco m. financi al int. aux. fin anc. real e state rentin g computer retail trade mineral meta ls mac hin ery el ectric al eq . transport eq . manu fact.o thers energy construc tio n sale,repai r wholesale tr ade pape r coke rubber wood mining food textile le ather 0,0 E3 These considerations are more evident looking at dynamism across economic sectors in terms of job created and destroyed. In 2001 gross turnover rate in terms of persons employed decreases from 9.2% for E1 to 5.9% for the real enterprise births and deaths (E3). Because of the exclusion of events, the turnover rate distribution (E2) shows peaks downward; in sectors like paper, coke, rubber, transport equipment and energy the trend has gone into reverse; for some activities in services such as transport, post & telecommunications and financial intermediation there is a drop in values. Hotels and retail trade are affected by the continuity rules applications; in fact turnover rates of E3 differ from those of the other two distributions. From these results it seems that sectors highly concentrated record a major number of events of structural changes; on the other hand, there are activities characterised by low entry barriers where it is likely to find links for continuity (i.e. change in the legal form, inheritance succession). In fact sectors characterised by small size present simpler structure in organisation that facilitate changes in ownership and localisation. To measure the strength of the association between the three rates, it is calculated a rank-order correlation index (r-Spearman 7 ) on the gross turnover rate in terms of enterprises and persons employed (Table 1). This index, based upon the difference between ranks held by different sectors with respect to the turnover rate, measures agreement/disagreement between ranks, the closer it is to 7 The r-Spearman is a non-parametric (distribution-free) rank statistic, r= 1 6 statistical rank of the indicator values 6 d2 N ( N 2 1) , where d is the difference in 1 the higher the correlation. In this context the r-Spearman index is used to understand whether dynamism of economic activities changes when measured by three different subset of data. Table 1- Ranking of economic activities according to gross turnover rates in terms of enterprises and persons employed Economic activities Enterprise gross turnover rate E1 E2 Employment gross turnover rate E3 E1 E2 E3 Mining 30 29 30 29 23 23 Food 20 20 22 20 18 18 Textile 11 10 10 18 13 14 Leather 13 12 17 16 12 15 Wood 29 27 26 22 16 16 Paper 19 19 19 14 20 21 Coke 27 28 28 13 27 27 Rubber 26 25 25 26 24 24 Mineral 24 23 22 27 22 22 Metals 23 22 24 24 19 20 Machinery 22 24 22 25 25 25 Electrical eq. 18 18 18 17 21 19 Transport eq. 15 15 13 12 26 26 Manufact.others 21 21 20 23 17 17 energy 25 30 29 21 29 29 6 6 6 6 5 5 sale,repair 28 26 27 15 11 12 wholesale trade 10 9 9 10 9 7 retail trade 16 14 16 7 8 8 7 7 15 8 6 10 construction Hotels transport 17 16 12 11 14 11 aux. Transport 9 11 8 19 15 13 post, telecom. 1 1 1 30 28 28 14 17 11 28 30 30 financial int. aux. Financ. 5 5 5 1 1 1 12 13 14 3 3 4 Renting 4 4 4 2 2 3 Computer 2 2 3 5 10 9 Research 3 3 2 4 4 2 other business 8 8 7 9 7 6 real estate The three r-Spearman values, that compare each ranking in pairs, indicate that data are homogeneous; in fact between E1 and E3, the r index calculated for enterprises is around 0.96 (between E1 and E2 is about 0.98). Comparing the r index calculated on employment, there is a relative significant change: between distributions E1 and E2 the value drops to 0.81 and then between E2 and E3 it does not change. This fact confirms how dynamism of economic sectors is influenced by the different impact of takeovers and mergers. Another way to analyse dynamics is to measure the growth/decline of a system. The chosen indicator is the net turnover rate, given by the difference between the number of enterprise births and deaths divided by the population of active enterprises. Net turnover rates are calculated both in terms of enterprises (Figure 4) and persons employed (Figure 5) by aggregated economic sectors. With reference to enterprises, apart from the used subset of data, net turnover rate is negative for industry and trade, close to zero for construction and high for services activities; the overall growth is positive for E3 in comparison to the very close to zero values of E1 and E2 rates. The most significant changes arise looking at growth in employment. It is more evident from Figure 5 a decrease in loss of employment strongly in industry (from –8% to –2.3%) and slightly in trade. 7 The overall net employment turnover rate without applying the methodology would be negative indicating how demographic flows would destroy more jobs than created. The real demographic component gives signals of a growth. Figure 4 - Enterprise net turnover rate - year 2001 3,0 2,5 2,0 1,5 1,0 0,5 0,0 -0,5 -1,0 Industry Construction Trade Services Total -1,5 -2,0 E1 E2 E3 Figure 5 - Employment net turnover rate - year 2001 6,0 4,0 2,0 0,0 -2,0 Industry Construction Trade Services Total -4,0 -6,0 -8,0 -10,0 E1 E2 E3 4 – Conclusions This paper confirms the necessity to apply a methodology for the treatment of data in order to identify the real demographic components. The identification process of new enterprises has been summarised into three main steps that allow to obtain three different subsets of data on which indicators are calculated. The first set is constituted by entries (exits) in the population of active enterprises (reactivations are excluded); the second subset is obtained by excluding units involved in events of structural changes; the third subset, the real enterprise births (deaths), is the result of the application of continuity rules through record linkage procedures and manual checks. With regards to enterprises the BD methodology impacts on levels of indicators whereas there are not significant changes in the economic activity distribution. In terms of persons employed indicators decrease in level and cause changes in the ranking of sectors that contribute to the job turnover; this result is mainly attributed to the exclusion of events. Moreover, the BD methodology application, especially for the adoption of continuity criteria, produces significant changes in the net turnover rate, the indicator of growth. Results demonstrate the importance to concentrate efforts in the identification of mergers and demergers; this means the necessity of more updated information on events and to increase the manual controls activities above all in presence of a large birth or death. 8