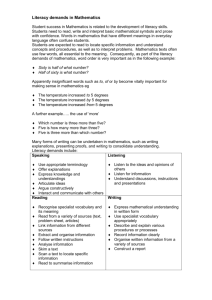

Mathematics Teaching and Learning

advertisement