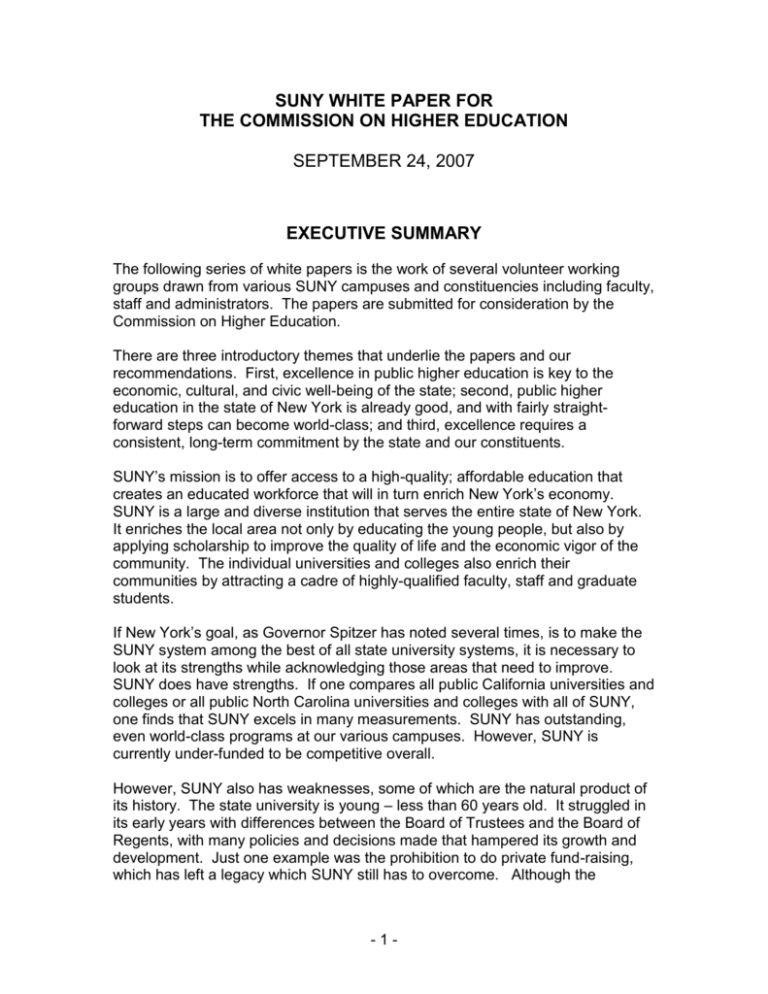

Proposed Tuition Policy for SUNY System

advertisement