There are six kinds of theory building

advertisement

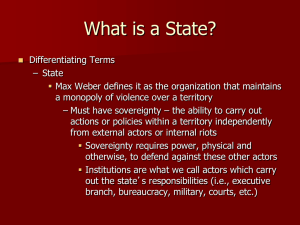

Some notes on case study methodology for Action COST project Draft (06-08-08) Salvador Parrado Table of contents CASE STUDIES AND THEIR RATIONALE .................................................................................... 1 CASE STUDY DESIGN ..................................................................................................................... 2 Research question ............................................................................................................................ 2 Research objectives .......................................................................................................................... 4 Specification of variables ................................................................................................................. 5 Case selection ................................................................................................................................... 6 Describing the variance in variables ................................................................................................ 8 Formulation of data requirements and general questions ................................................................ 8 CONSIDERATIONS FOR CASE STUDY DESIGN ......................................................................... 8 Causal mechanisms and process tracing: clarification notes ........................................................... 8 Typological theory: clarification notes ............................................................................................ 9 APPENDIX - RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM COST ACTION PARTICIPANTS...................... 9 LITERATURE ................................................................................................................................... 15 CASE STUDIES AND THEIR RATIONALE This note sets some options for discussing a case study methodology for COST Action project CRIPO. The note is subject to discussion (COST session in Rotterdam 5- September 2008) not only on the methodological aspects to be followed but also on the applied options for COST project. This section is devoted to justify the usefulness of case studies. Those who are already persuaded may skip it. Case studies are helpful in numerous ways. The definition offered by (Seawright and Gerring, 2008 p. 296) is useful: “the intensive (qualitative or quantitative) analysis of a single unit or a small number of units (the cases), where the researcher’s goal is to understand a larger class of similar units (a population of cases). There is thus an inherent problem of inference from the sample (of one or several) to a larger population. By contrast, a very different style of case study (so-called) aims to elucidate features specific to a particular case. Here the problem of case selection does not exist (or is at any rate minimized), for the case of primary concern has been identified a priori.” (Barzelay, 2007) identifies the first group as instrumental case studies (they are used to understand a bigger sample) and the second group is considered as intrinsic (or atheoretical driven and aimed at focusing on the richness of the case per se). This note focuses on the instrumental case studies, not on the intrinsic case studies. The use of case studies can be suited for well quantitatively explored areas (i.e. analysis of agencies through COBRA methodology) and for less statistically explored areas (i.e. role of agencies in policy-making). Firstly, in areas where statistical analysis has been undertaken (for instance, relation between agency autonomy and performance or agency autonomy and meritocracy of staff recruitment in Latin American countries), case studies may serve several purposes. In some instances, one might select deviant cases in order to understand their anomaly and their contribution 1 to theory. For example, Mexico has not a meritocratic general civil service; however, unlike all Latin American countries, four regulatory Mexican agencies are fully meritocratic. The question here would be: Why is this deviant case happening? And what does it tell of the general theory from which it derives? In other instances, one might select the most typical case (following the terminology by (Seawright and Gerring, 2008)in order to explore and understand causal mechanisms that are not apparent in the quantitative analysis. For instance, one might state that there is a causal (varying in degree) relationship between autonomy and agency performance. A typical case would be a representative case in relation to any kind of used cross-model. Basically, as the case is explained by the model (causal relationship between autonomy and performance), the researcher wants to dig into the case study in order to explore and understand the causal mechanisms at work (autonomy allows for selecting and paying more qualified staff / autonomy allows for using the best performing contractors… / autonomy allows for the use of more managerial techniques …). Those causes can be arranged in a single path (less likely) or in multiple paths (equifinality or multiple causes) (see some paragraphs on this below in the section Causal mechanisms and process tracing). Deviant and typical cases are just illustration of the use of case studies; there are other possibilities not explored here. Secondly, in an area not very well explored from the quantitative point of view, case studies can be useful in order to generate hypotheses or to test hypotheses derived from theoretical frameworks aimed at other research topics. For instance, cases studies on the role of agencies in policy-making could be crafted as generating hypotheses out of well selected cases or as testing hypotheses from frameworks of policy-making stemming from other areas (i.e. politicians-bureaucrats relationships; intergovernmental relationships…). A case study typically covers three phases: design, carrying out the empirical work and drawing the implications of case findings for theory. This note focuses on the first phase and it draws materials from (George and Bennett, 2005). For more practical questions on sampling cases and the empirical work, (Gerring, 2007) and (Seawright and Gerring, 2008)will be selected. While the focus is on design, the text will also refer some theoretical aspects and concepts to be used in the case study. The materials are organised as follows. For each task to be undertaken in the case study design there is a distinction between what is meant in this task (inserted in a Table) and what options or application of that meaning can be found for the COST Action project. CASE STUDY DESIGN Research question What is the research question (RQ) or puzzle to be solved? This is common to any methodology. In this case, the application will try to take into account what has already been done by COST Action participants. The participants of COST Action project have focused implicitly or explicitly (see also APPENDIX for more specific questions) on research questions related to the agencification process, the degree of autonomy, the control-coordination exerted by the parent ministry, the impact of agency autonomy on performance, and issues of accountability (also combined with control). For the case study, some of these research questions could be pursued in order to find the underlying causal mechanisms or process tracing (see the concepts below in the section on Causal mechanisms and process tracing). Derived from the research from COST Action participants, other research questions related to trust between parent ministry and agency (see Van Thiel and Yesilkagit 2008) or the influence of public agencies in policy making could be explored. Other items could be added to this additional list. For the sake of simplicity and only as an illustration, this note will focus on one research question 2 related to the role of agencies in policy-making that has been under explored. If the final selected RQ is different, some adjustments will be needed for the different parts of the case study methodology. The background for the research question on the role of agencies in policymaking is very similar to the literature on the relationships between politicians and bureaucrats and the role of bureaucrats in policy making. The rationale behind the implementation of agencies sets a more or less clear cut division between operations or delivery (agencies) and policy or decision making (parent ministry and? Parliament), although (Pollitt, 2004) argue that there are doctrinal and practical examples showing that this is not a universal trend. In any case, there is a widely shared view whereby agencies should not have an important role in policy making. This issue has not been intensively researched. A research question related to this could be: What is the role of agencies in policy making and how can it (or the different roles) be explained? This research question is relevant because it deals with: Accountability, transparency and legitimacy issues The role played not only by the agencies themselves, but also by parliament, professionals, interest groups, and civil servants from the ministry is highlighted Likely influence that agencies will have in how their performance and operations are undertaken, controlled, measured… Other arguments? What is the phenomenon or type of behaviour that is being singled out for examination? As (Barzelay, 2007) suggests, case studies should focus on processes (operating the Brazil in Action programme) and not on entities (tax agency). Further efforts should be devoted to define scoped (not to broad) “class” or subclass of phenomenon. The case studies would be of “the role of agencies in policy-making”. Probably, more specification would be required here to distinguish between policies related to the internal organisation of the agency and policies related to the field in which the agency operates. Is the goal to explain the lack of or an observable variation in the dependent variable? Depending on the ambition of the project, there are at least two options here: a) An expected lack of variation in the dependent variable should be found in agencies that are operating in: the same policy field, the same functions, with the same tasks, or belong to the same category according to different classifications. This implies in practical terms to select one field, function or task and analyse that role in different countries. In this case, the State tradition will have the explanatory burden. b) An expected variation of the dependent variable should be found in agencies belonging to different milieu (as described in a). What theoretical framework will be employed? If not, what provisional theories will be formulated by the researcher or what theory-relevant variables will be considered? There are also several possibilities here for which already implicit (or explicit) selection of independent and dependent variables are already made. a) One theoretical framework refers to the impact of types of policies on policy-making. Lowi (1964) and Wilson (1973, 1980) establish a classification of policies according to their purposes and consequences. They further argue that particular types of policies determine 3 the way in which decision-making and implementation of those policies are made. In Lowi’s typology distributive, redistributive, constitutional and regulatory policies are distinguished. In Wilson’s typology, the focus is on the dispersion or concentration of costs and benefits of different policies. There are other applications and even mergers of those typologies. Cases studies should be selected in relation to the cells produced by a table with types of policies and policy-making style. b) Another theoretical framework is referred as ‘bureau-shaping’ crafted by (Dunleavy, 1991 pp. 183-188). In this framework, agencies are classified as regards to their core and bureau budget into: delivery, regulatory, transfer and contract agencies. Dunleavy’s argument focuses on the relevance of the core budget for the maximization strategy of bureaucrats. In our case, the budget could be argued to have influence in the way in which the role of agencies in policy-making changes. c) A third theoretical framework has been recently labelled as Task-Specific Path Dependency by (Pollitt, 2004). In this collective effort there is a mixture between functions (forestry, meteorological services, prisons, social security benefits) and tasks using the typology from (Wilson, 1989). Wilson offers a typology of agencies as regards to the tasks that an agency performs. He takes into account the degree to which the outputs and outcomes of an agency can be observed giving birth to production organisations (tax agency), craft organization (inspection agencies), and procedural organizations (mental health counselling service). The implications of this could be derived from how the agency is managed and how they play a role in decision-making. Other possible theoretical frameworks could be added to this. The case study could either use one specific framework to be tested or use at least two of them as alternatives. If alternatives are chosen, it would require further care in the selection of the cases. Finally, some additional independent variables will have to be included in the framework (see below). From the specified theories, what aspects will be singled out for testing, refinement, or elaboration? This issue should be decided once a theoretical framework has been chosen. Research objectives There are at least six kinds of theory building-research objectives using (Lijphart, 1971) and (George and Bennett, 2005 75-76). A.- Descriptive or intrinsic (1) Atheoretical case studies / configurative idiographic. These cases provide thick description to be used for other studies for theory building (2) Interpretative case studies / disciplined configurative. These cases are selected because of the relevance or interest of the case and they use theories to explain it. The theory is used to shed light on the case rather than improve the generalization. The case study can be used to: a. Impugn the theory b. Highlight the need of new theories in some areas B.- Theory-building or instrumental case studies: (3) Hypothesis-generating case studies / Heuristic. In this type, new variables, hypotheses, causal mechanisms, and causal paths can be drawn out of the case study. 4 (4) Theory-confirming-infirming case studies / Theory testing. Case studies “assess the validity and scope conditions of single or competing theories”. According to (Lijphart, 1971 p. 692), the theoretical value of both types of case studies is enhanced, however, if the cases are, or turn out to be, extreme on one of the variables: such studies can also be labeled "crucial experiments" or crucial tests of the propositions.” (5) Plausability probes are used in order to check whether untested theories and hypotheses require more intensive testing. (6) Deviant case studies. These cases show why some cases deviate from the theory. (Lijphart, 1971 692) adds that “they weaken the original proposition, but suggest a modified proposition that may be stronger. The validity of the proposition in its modified form must be established by further comparative analysis.” A case study design could aim at achieving two or more purposes in some cases. The exemplified RQ for this note would be placed between point (4) Theory-confirming and point (3) Hypothesis-generating case studies Specification of variables The classical question of any research will be answered here. The dependent variable to be explained There are several options in order to analyse and make typologies of the dependent variable. Typologies would be of value if the case study aims at drafting typological theories (see the section below on Typological theory). A set of options stems from the analogy of distinguishing between decision making (policy) and delivery (operations) functions among ministries and agencies and the distinction between policy (ministers) and implementers (civil servants). Two possible frameworks are the following ones: “images” from (Aberbach, Putnam and Rockman, 1981) and “public service bargains” from (Hood and Lodge, 2006). In these cases, we should adapt the typologies replacing politicians through ministries and civil servants through agencies. a) (Aberbach, Putnam and Rockman, 1981 pp. 4-23) reduce the universe of possible relations among politicians and bureaucrats to four images: “policy-administration (politicians make policy; civil servants administer; facts-interests (both groups participate in policy making, but civil servants bring facts and knowledge and politicians values and interests); energyequilibrium (both groups engage in policy making and are concerned with politics, while politicians articulate broad, diffuse interests of unorganized individuals, bureaucrats mediate narrow, focused interests of organized clienteles); and, pure hybrid (virtual disappearance of the Weberian distinction between the roles of politician and bureaucrat”). b) (Hood and Lodge, 2006) use public service bargains. They are simply understood (p. 6) as the “explicit or implicit agreements between public servants – the civil or uniformed services of the state- and those they serve”. The authors identify 8 types of public service bargains (p. 21) out of the two main types: ‘trustee’ bargains and ‘agency’ bargains. These in turns are duplicated in two pairs (representational, tutelary) and (delegated, directed respectively). This framework could be adapted to the relationships between the ministry and the agency. Other different ways to look at the dependent variable come from policy analysis. c) The work on policy styles from (Richardson, 1982) offers one possibility for this. Richardson and co-authors focus on the likely convergence of “standard operating procedures for policy-making” (and also for implementation). They tried to capture the 5 universe into four different styles: (consensual, imposition relationship); (anticipatory-a active, reactive problem solving). d) A more dichotomous option is offered by (Gehring, 2004) when analysing regulatory agencies using Habermasian theory of communicative action. The author distinguishes between interest-based bargaining interactions and deliberative arguing. Of course there are other options that could be explored. The listing has stopped here until an agreement is made on the RQ. A crossing between the theoretical framework and the likely effects will produce numerous cells (depending whether variables are dichotomous or not). Most variables considered here are not dichotomous. This implies that the number of cells for which a case study can be made increases. However, there are techniques for reducing the number of cells, and we should also consider the trade-off between parsimonious explanations or more rich explanation including equifinality or multiple causes. Furthermore, the proposed typology will not be final until some preliminary empirical work has been undertaken. After a preliminary stage, the typology should be refined. The independent (intervening) variables considered in the theoretical framework. The independent variables will depend on the selected framework from above. Additionally, other variables should be considered like the role of Europe, the role of particular communities of professionals, just to name two clear examples that are absent from the theoretical frameworks from above. In general terms, the case studies should be selected on the independent variable (different or same sector; different or same function or task) and not on the dependent variable (instances in which policy-making is consensual according to the typology of (Richardson, 1982)) because it could otherwise lead to selection bias. Variables that will be held constant serving as parameters across case studies in different settings (countries, sectors…) and variables that will vary across cases. This issue is to be decided. One could set as constant the fact that all agencies comply to a similar degree with the three features that an agency might have according to (Pollitt, 2004). This degree of autonomy should be constant across countries and sectors; otherwise, they cannot be chosen for the study. Another different way to look at it is to choose sectors for which there are quasi-autonomous delivery units (agencies) and dependent units (ministries) in order to track differences in their role in policy making. Case selection The cases should be selected: On the basis of their relevance to the research objective of the study: theory development, theory testing, or heuristic purposes. On the variation- non-variation of the subclass to which case studies belong to. On a typology of processes to be researched. This will help to identify how many subclasses are available and whether all case studies should belong to one subclass or all subclasses should be analysed through a case study. For this section, the typology of (Seawright and Gerring, 2008) will be used. They distinguish the following case studies as being typical, diverse, extreme, deviant, influential, most similar, and most different cases. Each one entails a different quantitative or qualitative selection procedure. For instance, in order to select a typical case study, they look “for the smallest possible residual—( the distance between the predicted value and the actual (measured) value) —for all cases in a multivariate analysis.” (p. 299). A typical case can also be qualitatively identified. 6 Let’s imagine, for the sake of illustration, that we would like to select the most diverse cases. According to (Seawright and Gerring, 2008 p. 300), these case studies have the objective of achieving the maximum variance along relevant dimensions in the independent variable (X) or the dependent variable (Y) or a particular relationship between X/Y. If the focus is on one of the variables (it would be hypothesis seeking and exploratory), and if the focus is the relationship (it is hypothesis testing and confirmatory). According to this, one design would be of exploratory nature by trying to link agencies operating policies of distributional, redistributive and regulatory nature with policy styles. One caveat should be born in mind. It is almost impossible to categorize an agency, given the vast array of their tasks in many of them, according to a single category. Therefore, if a category is given, the particular task should be applied. For instance, the tax agency behaves in a domain with concentrated costs and diffused benefits (VAT) and in another domain with diffused costs and diffused benefits (income tax). So, the tax agency would fit two cells in Wilson’s typology (this labelling could also be controversial). In a very simplified way, in option 1, (hypothesis seeking), case studies should help to generate hypotheses about the relationship between policy types and policy style in the way in which agencies interact with ministries. After the case study, one may say that in distributive policies style of policy making is consensual (this should be tested – and hopefully confirmed - in other agencies within the same distributive type of policies) between the agency / ministry / parliament… while in regulatory areas it is an “imposition relationship”. Cells will be filled after the case study. Option 1: RQ: What is role of agencies in policy-making? How can differences be explained? Policy domain Distributive Example of an agency Tax agency special taxes) Policy style Redistributive Regulatory (VAT, Agency in charge of Regulatory agency on social benefits telecommunications Consensual Imposition relationship Fictional example. Attribution of examples is controversial.. In option 2, the theoretical framework already gives the options for other arenas (intergovernmental relations, for instance) and one has to confirm the hypotheses for the ministry-agency relationships. Cells are filled previous to the study. In both cases, the theoretical implications of the model as well as the likely results of crossing the independent variable with the dependent variable should be refined after a primary familiarisation with the case study materials. Option 2: RQ: What is role of agencies in policy-making? How can differences be explained? Policy domain Distributive Redistributive Regulatory Example of an agency Policy style Tax agency special taxes) Consensus-imposition Consensual Consensual Imposition Action-reaction Active Reactive Active (VAT, Agency in charge of Regulatory agency on social benefits telecommunications 7 Fictional example. Attribution of examples is controversial. Describing the variance in variables The description of the variance is useful for furthering the development of new theories or the assessment or refinement of existing theories. The process of describing the variance could be iterative and be modified after some preliminary research has been undertaken. Some relevant dimensions are: The variance can be described in quantitative and qualitative terms. In any case, a decision should be made in order to establish dichotomous or multi-category variables. The differentiation of types can be applied to the independent or the dependent variable It has not been applied to the Action COST project. Formulation of data requirements and general questions Data requirements should take the form of general questions to be asked for each case. Questions should not be crafted in specific terms that are only relevant to the case study in question. In addition to this, the researcher should bring to the case those idiosyncratic that help to explain the case, to be of interest for theory development or for future research. In order to look for adequate data and to frame general questions, the following concepts might be of help. It has not been applied to the Action COST project. CONSIDERATIONS FOR CASE STUDY DESIGN Causal mechanisms and process tracing: clarification notes The definition of (Mahoney, 2001 p. 580) suggests that “a causal mechanism is an unobserved entity that-when activated-generates an outcome of interest.” Casual mechanisms will be of interest in case studies because these unobserved entities (distribution of power for instance) will be responsible for outcomes. Ideally, we should be able to identify a difference in the outcome previous and after the causal mechanism took place. For that reason, it is important to define first the causal effect or outcome. The causal mechanism works as “X leads to Y through steps A, B, C”. Among the numerous problems linked to causal mechanism, one of them is to decide at what (micro) level stops the search for the causal mechanism (rational choicers stop at the individual level!). Causal mechanisms depend on the presence of other mechanisms or on the context. Context, then, should be specified in order to understand when a particular causal mechanism is taking place. A change of outcome might be produced by different causal mechanisms, and not always by a single causal pattern. This is known as equifinality (or multiple causality): when different causal patterns can lead to similar outcomes. (George and Bennett, 2005 206) also define process tracing as an important way to dig into case studies. “Process tracing is a method that attempts to identify the intervening causal process – the causal chain and causal mechanism- between an independent variable (or variables) and the outcome of the dependent variable.” (p. 207) “Process-tracing forces the investigator to take 8 equifinality into account, that is, to consider the alternatives paths through which the outcome could have occurred, and it offers the possibility of mapping out one or more potential causal paths that are consistent with the outcome and the process-tracing evidence in a single case. With more cases, the investigator can begin to chart the repertoire of causal paths that lead to a given outcome and the conditions under which they occur- that is, to develop a typological theory.” “In process tracing, all the intervening steps in a case must be as predicted by a hypothesis, or else that hypothesis must be amended- perhaps trivially or perhaps fundamentally- to explain the case. It is not sufficient that a hypothesis be consistent with a statistically significant number of intervening steps.” Typological theory: clarification notes (George and Bennett, 2005 pp. 235-ff.) maintain that, “in contrast to a general explanatory theory of a given phenomenon, typological theory provides a rich and differentiated depiction of a phenomenon and can generate discriminating and contingent explanations and policy recommendations.” Typological theory is “a theory that specifies independent variables, delineates them into categories for which the researcher will measure the cases and their outcomes, and provides not only hypotheses on how these variables operate individually, but also contingent generalizations on how and under what conditions they behave in specified conjunctions or configurations to produce effects on specified dependent variables.” “These categories of the variables for which the cases are to be measured could be nominal (such as democracy or nondemocracy), ordinal (such as high, medium, or low ranking of states in their protection of human rights), or interval (such as ranking percentiles of states by GNP per capita).” (p.238) “In a typology, in contrast to a typological theory, the constituent characteristics or combinations of factors are not necessarily theoretical variables. This is likely to be the case when the typology has not been developed within a theoretical framework. Nor does a typology itself link independent and dependent variables in a causal relationship. Types and typologies are at best only implicit theories or starting points for theory construction.” (p. 239) Case studies can contribute to the inductive development of typological theories in the early stages of a research program by identifying an initial list of possible theoretical variables. (p. 244) “In contrast to the inductive method, the deductive approach requires that the investigator first construct a theory-based map of the property space by defining variables and the types these variables constitute through all their mathematically possible configurations. Such a framework can then be reduced to the most useful types for the purposes of research design, case selection, and theory development”. APPENDIX - RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM COST ACTION PARTICIPANTS 1. When was the ‘autonomous agency model’ introduced in the country under study? How can we explain the adoption of this model in this country, at that time? For example, what was the political and economic context at the time? Did NPM ideas play a role? To what extent does agencification fit with existing politico-administrative traditions? 2. Why and under which conditions do politicians choose to create autonomous agencies? How can their decision be explained, e.g. is it a paradigm shift, or was it induced by self-serving motives? 3. How many and what type of autonomous agencies exist in the countries under study? And at which levels of government do agencies exist? 4. How can the institutional design of autonomous agencies be described, for example in comparison to other countries? For example, what is their legal status, hierarchical subordination, legal position of staff, way of financing, supervision arrangements, etc.? 9 5. What types and degrees of autonomy are attributed to autonomous agencies? How can this be measured? Are there different types and degrees of freedom for different types of agencies (task, size, policy sector, legal status), and if so how can these be explained? 6. How do politicians and parent departments steer/control/manage autonomous agencies? What kind of steering instruments are used or have been developed for this purpose (ex ante, ex post, performance indicators, contracts, and so on)? 7. How do agencies and parent departments balance the trade-off between autonomy and control (accountability, steering, audit, board, patronage)? What (new) instruments are developed for this purpose (e.g. new forms of accountability)? How do agencies cope with the actors and pressures of their environment (‘fit’)? 8. What coordination trajectories have been followed in several countries? 9. How specialisation affects coordination? 10. What is the impact of autonomy on performance? Most questions above can be summarised in the three questions that (Pollitt, 2004) have used for their research: Why has the agency form become so popular? How can agencies be best steered? Under what conditions do agencies perform best? 10 Main research questions and more specific subquestions of the Cost Action Table 1 presents the broader research framework and refers to the 5 basic research questions. In table 1 we have tried to elaborate these research questions in more specific subquestions for the two basic themes (autonomy and control on the one hand and proliferation and coordination on the other hand). General and specific research questions General and specific research questions on Autonomy, control and on Proliferation, coordination and organisational performance (WG1) systemic performance (WG2) 1. Descriptive WHAT-question: What is happening ? over time, space and tasks. 1.1. On the level of ideas 1.1. On the level of ideas When was the ‘autonomous agency model’ (or models) introduced in the country under study? What are the characteristics of this model? On what kind of normative ideas is this model based? What are the normative ideas about autonomy and control of public sector organisations? What are the normative ideas about proliferation and coordination of public sector organisations? (e.g. Is there a preference for more hierarchical ways of governance and coordination, or rather market- or network-based ways?). How does this evolve over time? document and discourse analysis, interviews with key respondents … document and discourse analysis, interviews with key respondents … 1.2. On the level of general mapping of agencies and agency-related reforms 1.2. On the level of general mapping of agencies and agency-related reforms How many and what types of autonomous agencies (or more general public sector organizations) exist in the countries under study? How does their institutional design look like1? In which policy fields and with which tasks? What is their importance in the state apparatus? What is the proliferation of public sector organisations and agency-like bodies (in general, in different policy fields, with different tasks) ? What is the evolution of agencies over time? document respondents … analysis, interviews with key document respondents … analysis, interviews with key answers to these questions can be largely based on the mapping van public sector organisations/agencies (see question 1.2. within the theme on autonomy and control) 1.3. On the level of individual agencies 1.3. On the level of groups of agencies What is the level of autonomy of these bodies? How are these bodies controlled by their political How are these bodies coordinated by their political principals/parent department/ central departments/ other actors (vertical coordination)? How do they 1 How can the institutional design of autonomous agencies be described, for example in comparison to other countries? For example, what is their legal status, hierarchical subordination, legal position of staff, way of financing, supervision arrangements, etc.? 11 General and specific research questions General and specific research questions on Autonomy, control and on Proliferation, coordination and organisational performance (WG1) systemic performance (WG2) principals/parent department/ other actors? How does this change over time, policy fields and tasks?2 survey (e.g. COBRA) or case studies … coordinate and collaborate among themselves (horizontal coordination)? What instruments and mechanisms of coordination are used to join up actors in a specific policy field? How does this change over time and tasks? survey (e.g. COBRA) or case studies … 2. Explanatory WHY-question: Why is this happening? – Why is this like that? 2.1. On the level of ideas 2.1. On the level of ideas How can we explain the adoption of the ‘autonomous agency’ model in this country, at that time? For example, what was the political and economic context at the time? Did NPM ideas play a role? To what extent does agencification fit with existing politico-administrative traditions?3 document and discourse analysis, interviews with key respondents … How can we explain the adoption of a specific coordination model in this country, at that time? For example, what was the political and economic context at the time? Did NPM ideas play a role? To what extent does the type and shift of coordination fit with existing politico-administrative traditions? 2.2. On the level of general mapping of agencies and agency-related reforms - document and discourse analysis, interviews with key respondents … Why and under which conditions do politicians choose to create autonomous agencies? How can their decision be explained, e.g. is it a paradigm shift, or was it induced by self-serving motives4? document analysis, interviews respondents, case studies … with key 2.3. On the level of individual agencies 2.3. On the level of groups of agencies Which factors (e.g. task, date of creation, policy field...) help to explain the level of autonomy and the kind of control of these bodies ? Why are specific instruments and mechanisms of vertical/horizontal coordination used in specific circumstances (e.g. in different policy fields)? How 2 What types and degrees of autonomy are attributed to autonomous agencies? How can this be measured? Are there different types and degrees of freedom for different types of agencies (task, size, policy sector, legal status), and if so how can these be explained? (See review note of WG leaders on autonomy and control for the meeting in Madrid written by van Thiel, Barbieri and Yesilkagit) How do politicians and parent departments steer/control/manage autonomous agencies? What kind of steering instruments are used or have been developed for this purpose (ex ante, ex post, performance indicators, contracts, and so on)? How do agencies and parent departments balance the trade-off between autonomy and control (accountability, steering, audit, board, patronage)? What (new) instruments are developed for this purpose (e.g. new forms of accountability)? How do agencies cope with the actors and pressures of their environment (‘fit’)? (See review note of WG leaders on autonomy and control for the meeting in Madrid written by van Thiel, Barbieri and Yesilkagit) 3 See review note of WG leaders on autonomy and control for the meeting in Madrid written by van Thiel, Barbieri and Yesilkagit. 4 See review note of WG leaders on autonomy and control for the meeting in Madrid written by van Thiel, Barbieri and Yesilkagit. 12 General and specific research questions General and specific research questions on Autonomy, control and on Proliferation, coordination and organisational performance (WG1) systemic performance (WG2) survey (e.g. COBRA) or case studies … can we explain shifts over time with regards to the mechanisms and instruments of coordination used? case studies or survey … 3. Evaluative EFFECT-question: What are the effects of this? 3.1. What is the effect of agencification on the functioning and performance of agencies? What is the effect of autonomy and specific ways of control? What are strengths and weaknesses? survey (e.g. COBRA) or case studies (document analysis, interviews) … 3.1. What is the effect of proliferation and coordination on the performance at the level of policy sectors or groups of organisations? What is the effect of specific ways of coordination? What are strengths and weaknesses? case studies (document analysis, interviews) or surveys… 3.2. How to measure organizational performance? 3.2. How to measure systemic performance? Elements like COBRA)5: Elements like (see e.g. literature on coordination and on network performance): • • • • • • • (see Boyne 2002/2003; see Internal management Outputs: quantity and quality of services Efficiency: input/output ratios Effectiveness: achievement of formal goals Responsiveness: including satisfaction by users, citizens, staff Democratic outcomes: accountability, equity, probity, participation Impact • • • • • • Degree of actual level of cooperation and collaboration between actors Strengths of networks Extent of well-coordinated policy / uniformity in implementation Policy impact and effectiveness.... Accountability at the level of policy sectors Stability / flexibility of the system 4. Normative question: How should it optimally be? What can we learn for practice? 4.1. What lessons can we learn for the practice of agencification, agency autonomy and control? 4.1. What lessons can we learn for the practice of agency coordination? 5. Conceptual and theoretical question: What theories have most explanatory power in this regard? 5.1. What concepts and theories are appropriate to interpret and explain 5.1. What concepts and theories are appropriate to interpret and explain - changes in ideas - changes in ideas - creation of agencies - proliferation of agencies - level of autonomy and control - (changes in) level and kind of coordination - effect of agencification, autonomy and control - effect of proliferation and coordination Table 1. detailed research questions 5 See the review note on performance related research by Hammerschmidt and Randma for the meeting in Madrid 13 14 LITERATURE Aberbach, J. D., Putnam, R. D. and Rockman, B. A. (1981) Bureaucrats and politicians in western democracies. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Barzelay, M. (2007) 'Learning from Second-Hand Experience: Methodology for ExtrapolationOriented Case Research', Governance, 20 (3), 521. Dunleavy, P. (1991) Democracy, bureaucracy, and public choice : economic explanations in political science. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Gehring, T. (2004) 'The consequences of delegation to independent agencies: Separation of powers, discursive governance and the regulation of telecommunications in Germany', European Journal of Political Research, 43 (4), 677-698. George, A. L. and Bennett, A. (2005) Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Gerring, J. (2007) Case study research : principles and practices. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press. Hood, C. and Lodge, M. (2006) The politics of public service bargains : reward, competency, loyalty - and blame. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. Lijphart, A. (1971) 'Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method', The American Political Science Review, 65 (3), 682-693. Mahoney, J. (2001) 'Beyond Correlational Analysis Recent Innovations in Theory and Method', Sociological Forum, 16 (3), 575. Pollitt, C. (2004) Agencies : how governments do things through semi-autonomous organizations. Hounmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan. Richardson, J. J. (1982) Policy styles in Western Europe. London ; Boston: Allen & Unwin. Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) 'Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options', Political Research Quarterly, 61 (2), 294. Wilson, J. Q. (1989) Bureaucracy : what government agencies do and why they do it. New York: Basic Books. 15