Retention and Institutions - Supporting students at a distance

‘RETENTIONEERING’ HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE UK: ATTITUDINAL

BARRIERS TO ADDRESSING STUDENT RETENTION IN UNIVERSITIES.

Veronique Johnston, Academic Development Adviser & Teaching Fellow,

Napier University, Edinburgh;

Ormond Simpson, Senior Lecturer in Institutional Research, Institute of

Educational Technology, Open University

Abstract

This article argues that universities’ attitudes to student retention are essentially ambivalent. For example, increased retention can be seen as a sign of lower academic standards and thus lower institutional status. The authors suggest that this need not be the case and that retention can be increased with no effect on standards. However ‘retentioneering’ an institution in this way is likely to require substantial changes in institutional structures and staff attitudes. This article suggest ways in which such attitudes can be understood and possibly changed.

Address for correspondence

Ormond Simpson ormond.simpson@gmail.com

‘RETENTIONEERING’ HIGHER EDUCATION IN

THE UK: ATTITUDINAL BARRIERS TO ADDRESSING STUDENT

RETENTION IN UNIVERSITIES.

Introduction

Universities are curious entities. Individual universities have existed longer than almost any form of social structure other than the Church. Yet arguments about their functions continue as fiercely as ever (Denman, 2005). Central to their

1

existence for example is the tension between research and teaching, which is still the subject of debate. This article will argue that there is also a fundamental tension in institu tions’ attitudes towards one of their other important functions – the successful production of graduates.

This tension is most clearly manifested in attitudes to student retention and is perhaps illustrated in the comment made by the Managing Director of a small manufacturing enterprise in a survey undertaken by one of the authors

(Simpson, 2003):

“Our businesses are not that different. We both take in tested raw materials and turn out a finished product. The difference is that I have to aim for at leas t 99.99% success rate for my products otherwise I’ll go out of business.

You people in universities only have a success rate of 70% and seem happy with that.”

This may not be a fair comparison. But are universities sanguine about the waste of human resources involved in current educational policies? If raw materials in the shape of students are tested before they arrive then how far is it the responsibility of universities if substantial numbers of them then fail? An average of 23% of United Kingdom students starting during 1996/97 to 2003/4 will not gain a degree according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency

(HESA) performance indicators. And if government widening participation strategies succeed, then what implications will this have for future student retention and success?

Institutional Attitudes to Retention – Anderson’s model

2

Institutions’ attitudes to the enduring and complex problem of improving student retention are ambivalent (The Guardian, 5 October 2004). Allen and Fifield

(1999) note that Universities generally lack customer-orientation in their processes, partly as a consequence of entrenched values and institutional politics. Similarly, Newton (2002) warns that ‘there are dangers in viewing organisations as entirely rational entit ies’. With respect to attitudes to students,

Anderson (2003) maintains that there are two kinds of higher education institution

– the ‘Survival of the Fittest’ or ‘Survivalist’, and the ‘Remedialist’. He suggests that the two types of institution are distinguishable by their attitudes and policies towards new students at admission, support after starting their course and the overall outcomes that are desired

– see Table 1.

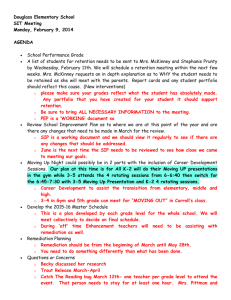

‘Survivalist’ Institutions ‘Remedialist’ Institutions

1. Admissions

Policy

2. Support

During

Courses

3. Expected

Outcomes

Retention strategy centres on a strict admissions policy

Essentially ‘hands-off’ with the expectation that students will be self-motivated and self starting and only need support when faced with extreme pressures

High retention and the production of independent, confident and competitive graduates

Emphasis on marketing and recruitment and a flexible attitude towards entry qualifications

Committed to students’ remedial support. But students are expected to identify their own weaknesses and to be sufficiently assertive to ask for help.

Expectation that remedial support will reduce student wastage.

Table 1. Contrasting Features of ‘Survivalist’ and ‘Remedialist’ Institutions

1. Admissions policy.

In ‘survivalist’ institutions, Anderson argues that student retention strategy centres on admissions policy. The key is to refine selection procedures to identify those most likely to succeed. This usually means selecting the very top

3

grades of the entry qualifications, a strategy which is demonstrably successful as research points to a clear relationship between students’ educational qualifications on entry and their subsequent retention (Simpson 2003, House of

Commons Education & Skills Committee 2003, Woodley et al 1992). Of course, such selection can never be entirely accurate; there are always likely to be false positives – students who are selected but fail, and false negatives – students who are not selected but could have achieved as well or better than those admitted.

This remains a serious problem for survivalist institutions.

‘Remedialist’ policies on admissions are rather more complex. Ostensibly fulfilling the same criteria as survivalist institutions, the actuality can be rather different. The emphasis is heavily on marketing and recruitment in order to stimulate demand (The Guardian, Wednesday February 8, 2006) and the attitude towards entry qualifications can be flexible:

“[I have just offered a place to a student] …with two D grades. Normally two

C’s are required but he’s local and that helps” (University Admissions Officer quoted in the Guardian 19 th August 2003).

2. Support during courses.

Anderson maintains that the approach of ‘survivalist’ institutions to support poststart is simply ‘hands off – it’s up to the students’. Whilst this is an oversimplification, such institutions have very high expectations of their students, amongst which are that students will be self-motivated and self starting and only need support when faced with extreme pressures resulting perhaps from external events. Even then, it is expected that students will be sufficiently perceptive to recognise their needs and sufficiently assertive to seek help when they need it.

4

‘Remedialist’ institutions are committed to students’ remedial support as they have admitted students with lower entry qualifications than survivalist institutions and therefore likely to generate more ‘false positives’ and a considerably lower retention rate. However, the support offered is generally reactive in nature – students are still largely expected to identify their own weaknesses and to be able to ask for help.

3. Expected outcomes.

As a result of its admissions and support policies the ‘survivalist’ institution expects to have very high retention and to produce independent, confident and competitive graduates. The consequence of the production of such graduates is that the institution expects to be seen as having high status and academic standards.

‘Remedialist’ institutions expect lower retention but that remedial support will reduce student wastage ( Yorke & Thomas, 2003).

Institutional attitudes to retention - other models

Whilst Anderson’s analysis is taken from US higher education there may be similarities to the UK worth examining. There may for instance be links between his analysis and the increasing divide in the UK between research and teaching intensive universities. There is certainly a close resemblance between

Anderson’s model and Martin Trow’s (1973) distinction between ‘elite’ and ‘mass’ higher education where the attitude of elite institutions to issues such as access to higher education is that it should be seen as a privilege whereas mass institutions are supposed to perceive it as a right. There may be similar links

5

between Anderson’s model and attitudes and concepts derived from psychological theories of the self (Dweck, 2000); that is between ‘entity’ theorists of intelligence who believe that intelligence is fixed and immutable and might therefore be identif ied with survivalist attitudes, and ‘incrementalists’ who believe that intelligence can be changed through effort and support, and who therefore might be seen as remedialists.

Institutional attitudes to retention

– an essential ambivalence

The factors influencing student retention are inherently complex and problematic

(Tinto, 1993). Curiously, it is where institutions are successful in reducing drop out rates that institutional ambivalence to retention is most keenly felt as

‘remedialist’ institutions may already suffer relatively low status. Read et al

(2003) comment that ‘institutions which receive a large number of non-traditional students are subsequently constructed as ‘sub-standard’ and to some extent, therefore, ‘inauthentic’ institutions. As higher drop out is linked to a poorer quality student intake, a fall in drop out places an institution in danger of being accused of lowering its academic standards (THES, 19 November 2004). Thus there will be pressures on ’remedialist’ institutions to adopt the strategies associated with

‘survivalist’ institutions as well as their ethos. This will not be true of all staff in the institution but in general ‘remedialist’ institutions may very well be infused by staff with ‘survivalist’ attitudes.

As Peter Scott (1995) notes, the British have found themselves with a mass system of higher education in terms of ‘public structures’ but with an elite one in terms of ‘private instincts’. Thus some staff may maintain that students should be offered help but that if they do not take it up then the institution is not

6

obliged to make further effort. For by not taking up help, students reveal themselves to be those who are destined to dropout anyway and thus in effect, be part of the dropout needed to maintain standards. So institutions offer help reactively to those students who seek it but do not necessarily see the need to give support proactively to those students who do not respond immediately to offers of help. Such an institution is illustrated in the quote below:

‘In the first year at X University students are not closely monitored. There are few coursework marks available before late in the year and what does exist is not used to identify weak or unmotivated students. Staff started taking attendance data this year but have yet to decide what to do with it, tutorials sessions with academics are available weekly but most students choose not to attend. The general ethos is that staff make available learning and support opportunities but if students don’t take advantage of them there is little comeback’ (from a UK listserv 2003).

Of course, as universities are made up of individuals, no institution is entirely survivalist or remedialist. Institutions will fall somewhere in the spectrum between these two approa ches. A ‘survivalist’ institution will certainly support those of its students who are experiencing external difficulties. Students experiencing academic difficulties will also receive help although a point may soon be reached where they will be deemed beyond help. But, as suggested above, there will also be ambivalent attitudes in ‘remedialist’ institutions which may also be subject to survivalist attitudes (THES, 19 November 2004), even if the point at which students will be deemed to be beyond help is later in their progress than in ‘survivalist’ institutions.

7

This ambivalence is central to shaping efforts to increase student retention in UK higher education institutions and it may be the biggest single barrier to developing appropriate strategies. But such ambivalence is increasingly difficult to sustain in the face of the Government’s determination to widen participation in higher education, evidenced by the Higher Education Statistics

Agency’s participation performance indicators (HESA, 2006), the recent establishment of the Office for Fair Access (OFFA, 2005) and high profile media rewards for widening participation activity such as the annual Times Higher

Educational Supplement (THES) ‘Widening Participation Initiative of the Year’.

Indeed, there appears to be growing recognition amongst some of the principle

‘survivalist’ institutions that relying only on entry qualifications and interview, may be producing false negatives amongst students from relatively deprived educational backgrounds who have lower entry grades (The Guardian, 18

December 2002, The Scotsman, 10 November 2004). They are therefore exploring the possibility of adjusting their admissions processes. However, evidence suggests that this is likely to be accompanied by a decrease in retention unless the issues of attitudes and policies are addressed at the same time (Furlong & Forsyth, 2003).

Improving retention

If institutions are to merely maintain current retention levels, let alone increase them, then new approaches will be necessary. Anderson (2003) argues that reactive contact with students is not enough to affect retention rates significantly

– “Student self-referral does not work as a mode of promoting persistence.

Students who need services the most refer themselves the least. Effective

8

retention services take the initiative in outreach and timely interventions.” In other words there is a need to recognise that many students at risk of dropping out are likely to have a limited ability to recognise and diagnose their own weaknesses, and are also likely to be insufficiently assertive to respond to offers of help. In essence, institutions will need to move beyond ‘survivalist’ and

‘remedialist’ reactive modes of student support to ‘retentionist’ proactive modes.

There is considerable evidence that proactive modes of support has marked retention effects (Simpson, 2003).

Both remedialists and survivalists may argue that this is ‘force-feeding’ students. The thesis of this article is that proactive support is a response to the fact that new students from widening participation backgrounds will need more active support if they are to survive. It may no longer be possible to rely on such students being sufficiently assertive to seek support (Yorke & Thomas 2003).

Zepke et al (2006 ) conclude that improving student retention requires the institution to accept and recognise diverse learners goals and cultural capital and adapt their mores and practices to accommodate these in a learner-centred way.

It is also a thesis of this article that retention can be increased without any reduction in academic standards. There is evidence of this from various sources such as the work carried out at Napier University (Johnston, 2001) where despite increasing diversity increases in retention of 9% have been achieved in first year pass rates without any effect on course standards. In part-time higher education, increases in retention of 3-4% have been made at the United Kingdom Open

University (UKOU) by proactive contact with students, again without any effects on course standards (Simpson, 2003). Whilst such retention gains may seem

9

small there is evidence that they may be significant in terms of the positive benefits for students, institutions and society as a whole (Simpson, 2005).

Of course some dropout is inevitable through illness, employment domestic circumstances and so on. This is ‘institutionally unavoidable dropout’ and, for example, from considerations of the entry characteristics of UKOU students Simpson (2003) suggests that the maximum possible increase in retention in the UKOU lies somewhere between 7 to 12%. Thus 3% may represent nearly half of the maximum increase that could be achieved through institutional action. Different institutions will have different levels of ‘unavoidable’ dropout that may be similarly calculable and thus allow the setting of realistic targets for improved retention.

In addition many staff in higher education will argue that there will always be students for whom dropping out is the ‘right’ decision. This is undoubtedly true, but there seldom seems to be any estimates of how much this ‘rightful’ dropout should be, and there is the uneasy feeling that such a phenomenon is something of an excuse for the application of survivalist policies. Given that there is evidence of the negative effects of dropping out of university such as increased levels of depression, lower pay, higher unemployment, physical illhealth and partner violence (Bynner et al 2001) it would seem unwise to accept the current level of ‘rightful’ dropout uncritically.

Barriers to retention

If the case for increasing retention is accepted then what are the barriers to that objective? If it thought desirable to convert universities from ‘survivalist’ and

‘remedialist’ institutions to ‘retentionist’ institutions, we suggest that there will

1

0

need to be a change in sectoral and institutional attitudes. Critically, institutions have to recognise retention as a priority (Beatty Guenter, 1994) and to believe that change is possible. However, there is great comfort to be drawn from inertia and existing cultures are extremely tenacious. The status quo may not be perfect but does represent a form of agreement. Change that benefits the institution does not necessarily bring benefits to all the individuals in that institution and critically can disrupt the distribution of power. Those threatened with loss of power are unlikely to give it up lightly (Trowler et al, 2003).

Efforts to stimulate change are further complicated by the unique features of each institution. ‘The size, stage of development, strategic priorities, blend of organisational politics and even the particular vulnerabilities of a college are key considerations. They represent a complex combination of constraint and opportunity.’ (Newton, 2002).

The most important route to retentioneering an institution and its staff may be to identify implicit ‘survivalist’ attitudes and unwrap them so that they can be recognised and addressed with a view to transforming them. For example in the period of writing this article one of the authors was in correspondence with an administrator in his institution over a decision, made on grounds of economy, to withdraw the paper application form from its brochures and require applicants to apply online or by phone. In response to a query suggesting that this decision might disadvantage potential students who did not have easy internet or phone access, the administrator responded that perhaps these then were students we did not want – an archetypal survivalist attitude.Transforming attitudes

Transforming such attitudes will probably have to be achieved through processes of motivation and empowerment at sectoral and institutional levels. (Table 2)

1

1

Critical Factors Sectoral Level

Motivation Finance

Environment

Reputation

Performance Indicators

Empowerment ‘National Centre for

Retention Studies’

‘Retention awards’

Institutional Level

Leadership

Institutional Values

Finance

Reputation

Institutional Learning /Feedback

Planning Process

Resource

Challenging entrenched values

Rewarding individual endeavour

Table 2: Critical factors in Transforming Institutional and

Individual Attitudes to Student Retention

1. Sectoral Level Motivation and Empowerment

The ambivalence felt by many institutions about improving retention is in part due to its complexity and means that while there may be institutional will for change, it may be insufficient to overcome inertia without substantial pressure from the government through funding councils. Motivation to widen access to higher education has been strongly enhanced through wider access monies, the articulation of an inclusive agenda (DfES, 2003, Universities UK, 2003) and the development of HESA access indicators (2003) to measure institutional performance against benchmarks. Where financial carrots have been insufficient, the government has used the press to wield sticks to beat any

‘prestigious’ institution that has failed to meet their access benchmarks. (The

Guardian, Wednesday December 18, 2002).

1

2

The sectoral response to improvements in retention has been more equivocal, but increasingly access monies have become explicitly linked to retention (Scottish Higher Education Funding Council Joint Corporate Plan 2003-

06). Further motivation exists in terms of published dropout and graduation rates (HESA, 2003) and moves to reduce the per capita funding for students in the early years of HE in line with FE funding. However the government and funding councils need to do more to motivate institutions to work harder at improving student success. For example, there is little co-ordinated activity to support institutions developing retention strategies or guidance as to which retention strategies will work. A National Centre for Retention Studies could be of considerable help in bringing together and developing resources based on international experience, supporting institutional learning and sharing of good practice.

The government also needs to shape the environment in which improvement is likely to take place and to be realistic about what is achievable as institutional efforts rarely lead to step changes in drop out rates (Barefoot, 2003).

Universities will need to be encouraged to make retention an important aspect of their reputation and recruitment so tha t ‘high standards and high retention’ become marketing tools. For example in the US there are annual ‘Retention

Awards’ offered by an educational consultancy which can then become part of an institution’s reputational promotion equipment.

However, while MPs and the press complain about ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees it is hard to envisage universities being encouraged out of survivalist attitudes (The Telegraph, 14 January 2003).

2. Institutional Level Motivation and Empowerment

1

3

Whereas the sector can shape the environment for change, it is the institution which must transform strategy into action. Given the level of ambivalence,

‘retentioneering’ can only be realised with the whole-hearted support of senior management both in terms of setting retention goals and developing the strategies, motivators and rewards to achieve them (Elton, 1993). Consequently improving retention has to be a key strategic priority and an integral part of the planning process at all levels. Such leadership is also invaluable to keep momentum going when the ‘easy’ issues have been addressed.

Not only do institutional attitudes and values have to change, they have to be seen to have changed. Regular opportunities to reinforce the retention message are essential

– in particular measurements of student success should be incorporated into the key performance indicators set for academic departments on an equal par with applications. Failure to retain should cause the institution just as much alarm as failure to recruit. And while senior management may be aware of the link between the institution's government grant and retention, it is unlikely that this has been communicated to the rest of the institution in any simple way. That will need to be a priority. One possibility may be to convert the consequences of drop out into the resultant financial loss for academic departments. It should be possible to make it much clearer that increasing retention is to the institution’s advantage thereby enhancing security and opportunities for individuals.

Along with the new emphasis on tracking and monitoring, there should also be a willingness to use persuasion and debate in preference to diktat. The involvement of staff is critical to developing solutions and engendering a sense of ownership. However empowering institutional change requires considerable

1

4

energy and is linked to institutional learning and feedback, planning processes, resource, a willingness to challenge entrenched attitudes and rewards for individual endeavour (Elton, op cit). Taking these in turn:

(i) Institutional Learning and Feedback . A critical first step in addressing retention is understanding which factors are both influential and capable of being influenced (Yorke, 2000). Not all student drop out can be prevented and, as recognised earlier, neither is it desirable that students continue in higher education against their choice or best interests. The advice to build institutional learning comes with a caveat, however. Black (2001) notes that common retention initiative pitfalls include both failing to gather retention data to identify problem areas but also getting lost in data gathering and not moving onto solutions.

The annual production of comparative performance statistics is vital to show long term trends. Much retention data is too complex to be easily interpreted so simple measures have to be found. Individuals will need access to retention data in a way that provides clear feedback on the retention effects of their teaching. But given the limitations suggested above this may need to be over some lengthy period. A research-informed approach is essential if academics are to be persuaded that firstly there is an issue to be addressed, secondly that the retention data are reliable and thirdly that the academic context is understood and incorporated into any solutions (Johnston, 2003).

(ii) Planning Processes . The importance of retention as a strategic goal has been discussed above. At the operational level, all institutional departments

(including non-academic departments) should be required to develop plans to articulate how they will support the institution in achieving its retention goals and

1

5

evaluate impact. However, the existence of a retention plan does not necessarily imply anything beyond minimum compliance. It is essential that the plans are the product of broad consultation with staff and that strategies are adapted to reflect the departmental context.

(iii) Resource . Many institutions respond to retention by setting up a committee to frame the problem. These committees often have very little in the way of resource or power to implement solutions. To be effective, ‘retentioneering’ should be championed by a senior member of management with the help of at least one staff member to drive the work forward. Additional resource should be identified for evaluating initiatives and disseminating any resultant good practice.

However, every solution should be evaluated not only for effectiveness but also for return on investment.

(iv) Challenging entrenched values and attitudes . The mindset that retention is beyond the power of the institution and is connected with decreasing academic standards or has a ‘natural’ rate which can’t be changed, will have to be met through gathering evidence to demonstrate that increasing retention through institutional action is possible without compromising academic standards. Such research should enable realistic targets to be set.

For example, in the UKOU attempts to increase retention are often met with the argument that the re are students who weren’t interested in passing courses anyway and students who transfer out. So it is necessary to estimate what those effects might be compared with the overall dropout. Such estimates have subsequently suggested that those effects only account for about 8% of the overall 50% dropout (OU Institute of Educational Technology 1999).

1

6

However, attitude changes also have to be accompanied by process changes because ‘bad systems wear out good people’ (Black, 2001)

(vii) Rewarding individual endeavour . Higher Education does not generally reward staff for abilities with students or their administrative expertise. And yet it is these characteristics which are most likely to lead to improved retention (Yorke

& Thomas, 2003). Institutions must find ways of rewarding staff financially or reputationally for improvements they make to the student experience. As long as research is the primary promotion criterion, staff will continue to expend their greater efforts in that direction. Institutions must incorporate a retention focus into their promotion structures. For example, promotion to Senior Lectureship at

Napier University is based on excellence in 2 out of 3 strands: teaching, administration and research. And the Teaching Fellowship scheme, which combines both financial and reputational reward, provides some counterbalance to the demands of the RAE.

However, institutions should also keep in mind that individuals may well feel powerless to effect noticeable change because their locus of control is relatively small. Improvements in retention are largely due to the combined effects of a group of individuals, and small retention increases may not lead to noticeable outcomes in small teaching groups. For example in the UKOU

Associate Lecturers who increase their retention by 4% will only see one student

‘saved’ every year because the number of students in their individual groups each year is about 25. It will be very hard to detect this amongst the statistical noise. Consequently it is important to help the individual value their contribution to both the student experience and the achievement of students over the lifetime

1

7

of their course. At this level, emphasising student success is more effective than emphasising retention.

Conclusions

The evident ambivalence to addressing student drop out is a consequence of both the inherent complexity of the issues involved and the ‘survivalist’ values which suffuse higher education and society generally. Concerns about perceived lowering of academic standards and university status, linked to a lack of unambiguous government and media support for improving retention, has lead to equivocal institutional responses.

Increasing student retention will not be an easy task as it involves addressing deep-seated attitudes in institutions and staff which may need considerable work to change. Above all there will need to be a recognition that widening participation means that new forms of institutional strategy will be necessary to ensure that the door to higher education will not simply be a revolving door. These new strategies will need to be proactive to ‘reach the quiet student’ (Bogdan Eaton and Bean) and to avoid the educational equivalent of the

‘inverse care law’ (Simpson 2004) which it has been suggested applies in health care – that is that the care provided goes proportionally to the more articulate and assertive whose needs are often less than those of the poor and disempowered.

References

Anderson, E. (2003) ‘Retention for Rookies’ - presentation at the National

Conference on Student Retention San Diego, Calif.

1

8

Allen, D.K. & Fifield, N. (1999), Re-engineering change in higher education.

Information Research , 4(3), http://informationr.net/ir/4-3/paper56.html

Barefoot, B. (2003) ‘ Higher education’s revolving door: confronting the problem of student dropout in US colleges and universities’ – paper presentation at the

Student Retention in Open & Distance Learning Symposium, May 27 th -28 th ,

Madingly Hall, Cambridge.

BBC, Tuesday, 14 January, 2003, 15:24 GMT

'Irresponsible' Hodge under fire. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/2655127.stm

accessed 2 June 2006

Beatty-Guenter , P. (1994), ‘Sorting, supporting, connecting and transforming:

Retention strategies at Community Colleges’,

Community College Journal of

Research , 18(2), pp113-129.

Black, J. (2002), presentation at AUA Conference: Recruitment & Retention , 30-

31 January, London.

Bogdan Eaton, S. & Bean, J. P. (1995), ‘An approach/avoidance behavioural model of college student attrition’, Research in Higher Education , 36(6) pp617-

645.

Bynner, J. and Egerton, M. (2001) ‘The wider benefits of Higher Education’ http://www.hefce.ac.uk/pubs/hefce/2001/01_46.htm

accessed 20 November 2006

De Rome, E & Lewin, T. (1984), ‘Predicting persistence at university from information obtained at intake’, Higher Education ,13, pp 49-66.

Denman, B.D. (2005), What is a university in the 21 st century?, Higher Education

Management and Policy , 17(2), pp9-28.

DfES, (2003) Widening Participation in Higher Education. www.des.gov.uk/highereducation/docs/wideningparticipation.pdf

accessed 2 June 2006

Dweck, C. (2000) ‘Self theories: their role in Motivation Personality and

Development’ , Psychology Press, Philadelphia

Elton, L. (1998) Managing Change in Universities , paper prepared for an Society for Research in Higher Education/Times Higher Education Supplement

/Committee of Vice Chancellors and Principals seminar, 30 April 1998.

Furlong, A. & Forsyth A.J.M., (2003) ‘ Losing out? Socio-economic disadvantage and experience in further and higher education’, Bristol/York: The Policy Press/

Joseph Rowntree Foundation

1

9

The Guardian, (2002) ‘Top universities still failing working class: Targets for wider access not met by elite campuses’ Wednesday December 18, 2002, http://education.guardian.co.uk/print/0%2C3858%2C4569663-

108229%2C00.html

accessed 2 June 2006

The Guardian, (2002) ‘University offers automatic places to local students’

Wednesday February 8, 2006, http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/news/story/0,,1705208,00.html

accessed 17

November 2006.

The Guardian, (2004) Access targets 'dumbing down' degrees, Tuesday October

5, 2004, http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/news/story/0,,1320357,00.html

accessed 17 November 2006.

HESA (2005) 00/40. ‘

Performance indicators in higher education . http://www.hefce.ac.uk/learning/perfind/ accessed 17 November 2006

House Of Commons Education & Skills Committee (2003), The Future of Higher

Education, Fifth Report of Session 2002-3, HC425-I, The Stationery Office,

London

Johnston, V. (2001) ‘By Accident or Design?’, Exchange 1 pp9-11 Open

University Milton Keynes

Johnston, V. (2003), ‘ Monitoring & Tracking Widening Participation Students’

,

LTSN Generic Centre Guide (Autumn 2003)

Newton, J. (2002) ‘Barriers to effective quality management and leadership: Case study of two academic departments’. Higher Education . 44, pp185-212.

Office for Fair Access (OFFA) (2005), ‘ Strategic plan, 200510’ , http://www.offa.org.uk/about/publications/ accessed 17 November 2006.

Open University (2000) ‘Student Survey Results’, Student Research Centre,

Institute of Educational Technology

Read, B., Archer, L. & Leathwood, C. (2003) ‘Challenging cultures? Student conceptions of ‘Belonging’ and ‘Isolation’ at a post-1992 university’. Studies in

Higher Education , 28(3), pp261-278.

The Scotsman (2004), ‘The university challenge’, Wenesday10 November 2004, http://news.scotsman.com/education.cfm?id=1296532004 accessed 17 November

2006

Scott, P. (1995) ‘ The Meanings of Mass Education’ , Open University Press

London.

2

0

Select Committee On Education & Employment, Sixth Report (1998) www.parliament.the-stationeryoffice.co.uk/pa/cm199798/cmselect/cmeduemp/264/26402.htm

accessed 2 June 2006

Scottish Higher Education Funding Council (SHEFCE) (2003) Consultation on a

Joint Corporate Plan 2003-06 Consultation paper HEC/02/03 www.shefc.ac.uk/library/06854fc203db2fbd000000f5274b21f5 accessed 2 June 2006

Simpson, O (2005) ‘The costs and benefits of student retention for students, institutions and governments’. Studies in Learning Evaluation Innovation and

Development (Australia) 2 (3) http://sleid.cqu.edu.au/viewissue.php?id=8 pp34-43 accessed 2 June 2006

Simpson, O (2004) ‘Democracy and Online Learning’ in ‘E-learning and

Democracy – critical perspectives on the promise of Global Distance Education’

Ed. Carr-Chelman, A. Sage Publications US

Simpson, O. (2003) ‘ Student Retention in Online Open and Distance Learning’

RoutledgeFalmer.

Simpson, O. (2003) ‘The future of Distance Education – will we keep on failing our students?’ Presentation at a conference ‘ The Fut ure of Distance Education’

Cambridge UK.

The Telegraph (2003), 'Mickey Mouse' degrees to vanish, 14 January 2003, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/main.jhtml?xml=/education/2003/01/28/tepAdegre1

4.xml

accessed 17 November 2006

Times Higher Education Supplement (2004), ‘ Poll reveals pressure to dumb down’ , 19 November 2004, http://www.thes.co.uk/search/story.aspx?story_id=2017750 accessed 17 November 2006.

Times Higher Education Supplement (2006), ‘ Widening participation award’ , www.thes.co.uk/search/tory.aspx?story_id=2019603 accessed 17 November 2006

Tinto V. (1993) ‘ Leaving college: rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition’ The University of Chicago Press, 2nd Ed, London

Trow, M. (1973) ‘Problems in the Transition from Elite to Mass Higher Education’,

Carnegie Commission on Higher Education.

Trowler, P., Saunders, M. & Knight, P. (2003) ‘ Change thinking, change practices: A guide to change for Heads of Department, Programme Leaders and other change agents in Higher Education’ . LTSN Generic Centre, York.

Universities UK (2003) ‘ Fair Enough? Wider access to university by identifying potential to succeed ’. www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/fairenough/#report accessed

2 June 2006.

2

1

Woodley, A., Thompson, M. & Cowan, J. (1992), ‘ Factors affecting noncompletion rates in Scottish universities’ , SRC Report No. 69. The Open

University.

Woodley, A. & Simpson, C. (2001) ‘Learning and Earning: Measuring 'Rates of

Return' Among Mature Graduates from Parttime Distance Courses’ Higher

Education Quarterly 55 (1) pp 28-41.

Yorke M. (2000), 'The quality of the student experience: what can institutions learn from data relating to non-completion?' Quality in Higher Education . 6(1) pp

61-75.

Yorke M. & Thomas L. (2003) ‘Improving the retention of students from lower socioeconomic groups’, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management ,

25(1), pp64-74.

Zepke, N., Leach, L. & Prebble, T (2006) ‘Being learner-centred: one way to improve student retention?’, Studies in Higher Education , 31(5), pp587-600.

2

2