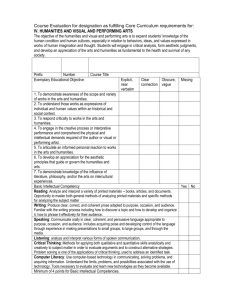

review of arts and humanities research funding

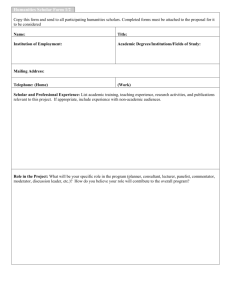

advertisement