BICS AND CALP

SESSION 2

The Needs of

English Language Learners and the

Process of Learning a New Language

Prepared by Illinois Resource Center

1

What are the specific needs of English language learners?

1. Connections to the knowledge, social/cultural values and experiences that they bring to the classroom.

2. Development of oral fluency and cognitive academic language proficiency (preferably in L

1 and L

2

)

3. Development of literacy skills (preferable in L

1

and L

2

)

4. Comprehensible instruction in social studies, science and math

5. Development of academic knowledge commensurate with their grade level peers

6. Instruction and assessment in a safe, low risk environment where their language and culture are valued

How do we address these needs?

Native language instruction and / or support with certified personnel

ESL instruction embedded in context – content based or sheltered” instruction

Purposeful interaction with English-speaking peers

Content curriculum alignment with district and state learning (in L

1

and

L

2

)

Student centered instruction which utilizes and connects the prior knowledge of English language learners to classroom activities

Fair and appropriate assessment procedures

Becoming a multicultural school through meaningful staff development

2

Comprehensible Input: when learners understand the message in the targeted language

Message vs. Form: when there is a focus on what is said, rather than on how it is said

Meaningful Communication: when language is used for communicating real ideas

Low Affective Filter: when the level of stress in the child’s environment/s is low

Source: Steve Krashen

3

BICS, CALP and CUP:

SECOND LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY AND LEARNING THEORY

Bilingual and English as a Second Language (ESL) educators commonly refer to two types of English language proficiency: Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills ( BICS ) and

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency ( CALP ). These terms were coined by Jim Cummins

(1980). Cummins found that while most students learned sufficient English to engage in social communication in about two years, they typically needed five to seven years to acquire the type of language skills needed for successful participation in content classrooms. Limited English proficient (LEP) students’ language skills are often informally assessed upon the ability of the student to comprehend and respond to conversational language. However, children who are proficient in social situations may not be prepared for the academic, context-reduced, and literacy demands of mainstream classrooms. Judging students’ language proficiency based on oral and/or social language assessments becomes problematic when the students perform well in social conversations but do poorly on academic tasks. The students may be incorrectly tagged as having learning deficits or may even be referred for testing as learning disabled.

The terms BICS and CALP tend to be imprecise, value-laden, simplified, and misused to stereotype English language learners (Baker, 1993). Cummins (1984) addressed this problem through a theoretical framework which embeds the CALP language proficiency concept within a larger theory of Common Underlying Proficiency ( CUP ). The three terms are discussed below.

Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS)

The commonly used acronym BICS describes social, conversational language used for oral communication. Also described as social language, this type of communication offers many cues to the listener and is context-embedded language. Usually it takes about two years for students from different linguistic backgrounds to comprehend context-embedded social language readily. English language learners can comprehend social language by:

observing speakers’ non-verbal behavior (gestures, facial expressions and eye actions);

observing others’ reactions;

using voice cues such as phrasing, intonations, and stress;

observing pictures, concrete objects, and other contextual cues which are present; and

asking for statements to be repeated, and/or clarified.

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP)

CALP is the context-reduced language of the academic classroom. It takes five to seven years for English language learners to become proficient in the language of the classroom because:

non-verbal clues are absent;

there is less face-to-face interaction;

academic language is often abstract;

literacy demands are high (narrative and expository text and textbooks are written beyond the language proficiency of the students); and

cultural/linguistic knowledge is often needed to comprehend fully.

4

Common Underlying Proficiency ( CUP )

Cummins’ common underlying proficiency model of bilingualism can be pictorially represented in the form of two icebergs. The two icebergs are separate above the surface. That is, two languages are visibly different in outward conversation. Underneath the surface, the two icebergs are fused such that the two languages do not function separately. Both languages operate through the same central processing system.

Social Language

L

1

Surface level

C ommon U nderlying P

(Central Operating System)

L roficiency

2

Language proficiency alone will not determine when English language learners are prepared to use their second language (L

2

) to learn with their grade level monolingual Englishspeaking peers. Previous schooling, academic knowledge, and literacy skills that second language learners have in their first language (L

1

) are also strong determiners (Cummins, 1984,

Baker, 1993 ). Cummins’ framework may be summarized as follows:

Regardless of the language in which a person is operating, the thoughts that accompany talking, reading, writing, and listening come from the same central engine. When a person owns two or more languages, there is one integrated source of thought.

Bilingualism and multilingualism are possible because people have the capacity to store two or more languages. People can function in two or more languages with relative ease.

Information processing skills and educational attainment may be developed through two languages as well as through one language. Cognitive functioning and school achievement may be fed through one monolingual channel or equally successfully through two well developed language channels. Both channels feed the same central processor.

The language the child is using in the classroom needs to be sufficiently well developed to be able to process the cognitive challenges of the classroom .

Speaking, listening, reading or writing in the first or the second language helps the whole cognitive system to develop. However, if children are made to operate in an insufficiently developed second language, the system will not function well. If children are made to operate in the classroom in a poorly developed second language, the quality and quantity of what they learn from complex materials and produce in oral and written form may be relatively weak.

Sources:

Baker, C. (1993). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J. (1980). The construct of language proficiency in bilingual education. In J.E. Alatis (ed.) Georgetown

University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

Cummins, J. (1984). Wanted: A theoretical framework for relating language proficiency to academic achievement among bilingual students. In C. Rivera (ed.), Language Proficiency and Academic Achievement. Clevedon: Multilingual

Matters.

Teacher Today, IER, Volume 5, No. 4, 1990

5

Levels of Language Proficiency -

Paired with Cummins’ Iceberg

Farquar came from Iraq a year ago at age 9. He only has about a year of formal education due to the war and subsequent closing of schools. Since entering school in the USA he has made little progress academically. What does his iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

Rosa was educated in Mexico City. She reads and writes at grade level in Spanish but has little to no academic skills in English nor does she speak English. What does her iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

Born in Los Angeles, Rafael speaks a mix of Spanish and English at home and school. He can converse quite well in both languages but is not making academic progress in either language. What does his iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

Sho-Win does fairly well in her bilingual class. She reads and writes at grade level in Chinese. She plays mostly with English-speaking children at recess and is understood by them although she has no English academic skills.

What does her iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

Rona’s mother reads to her at home each night in Romanian. At the age of ten she reads at grade level in Romanian and is beginning to read some English books. What does her iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

Lucia is able to converse with others fluently in both English and Spanish. She has moved quite frequently in her young life and is experiencing difficulty in all content areas including reading in both languages. What does her iceberg look like? What educational recommendations would you make?

6

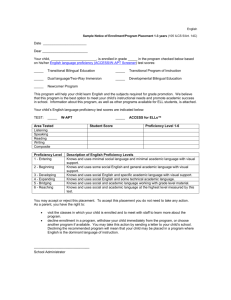

General Pattern of K-12 Language Minority Student Achievement on

Standardized Tests in English Reading

Compared Across Six Program Models

(Data aggregated from a series of 3-7 year longitudinal studies from wellimplemented, mature programs in five school districts)

© Wayne P. Thomas and Virginia P. Collier, 1997

Program 1: Two-way developmental bilingual education (BE)

Program 2: Late-exit bilingual education and ESL taught through academic content

Program 3: Early-exit bilingual education and ESL taught through academic content

Program 4: Early-exit bilingual education and ESL taught traditionally

Program 5: ESL taught through academic content using current approaches

Program 6: ESL Pullout-taught traditionally

1

2

Average performance of native-English speakers making one year’s progress in each consecutive grade.

3

4

5

6

1 3 5

GRADE

7 9 11

7

Program

Name

Two-way developmental bilingual

(Two-way

Immersion or

Dual

Language)

Developmenta l Bilingual

(Maintenance or Heritage

Language)

Duration

K-6

(K-8 or K-12 would be even better)

Language of

Instruction

L1 & L2

K-6

(K-8 or K-12 would be even better)

L1 & L2

Bilingual/ESL Program Models

Participants Setting

Language

Minority and

Language

Majority

Self-contained classroom

Comp/

Enrichment

Enrichment

Language

Minority

Self-contained classroom

Enrichment

Immersion K-8 L2 (L1 gradually) Language

Majority

Self-contained classroom

Enrichment

Pull-out or

Self-contained classroom

Compensatory

Staffing

Bilingual teacher Or

Team teach

(Eng. Dominant teacher &

Bilingual teacher)

Bilingual teacher

Or Team teach

(Eng. Dominant teacher &

Bilingual teacher)

L2 teacher

L1 teacher

Bilingual/ESL teacher

Linguistic

Outcome

Bilingualism

Biliteracy

Multiculturalism

Bilingualism

Biliteracy

Higher cognitive abilities

Biliteracy

Monolingual L2 Transitional

Bilingual

Sheltered

English

ESL Pull-out

English

Submersion

3 years test out or continued support if necessary

Any grade level as long as needed, test out

According to need, test out

L2

K-12

Begin with L1, transition to L2

(English) as quickly as possible

L2 (maybe some

L1)

Language minority

(same language)

Language minority

L2

Language minority

(different languages)

Language minority

Pull-out or

Self-contained classroom

Compensatory

Compensatory Resource room

Mainstream classroom

Compensatory

ESL teacher

Mainstream, content area teacher

ESL teacher

Mainstream

Mainstream teacher

Monolingual L2

Monolingual L2

Monolingual L2

8

BENEFITS OF USING STUDENTS’ NATIVE LANGUAGE

IN MULTICULTURAL SCHOOLS AND CLASSROOMS

The use of the native language:

Provides students access to academic content.

Allows students to have meaningful social interactions with their peers and adults.

Provides access to the students’ prior knowledge and experiences and connects their prior knowledge to current lessons.

Promotes (rather than detracts from) second language development.

Promotes self-esteem and identity and confirms to students that their home language and culture have value.

Allows students’ openness to learning by reducing language and culture shock.

Helps students develop their first language communication skills.

References: Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Reexamining English only in the ESL classroom.

TESOL Quarterly , 27, 9-32.

Lucas, T., Katz, A., (1993). Reframing the Debate: The roles of native languages in

English- only programs for language minority students. TESOL Quarterly, 28, 537-561.

Suzanne Wagner

1995

9

Role of Paren ts When They Don’t Speak English

Foster literacy development by reading books and telling stories to children in home language.

Work with their children with home writing materials stored in one accessible location.

Draw pictures, write stories, and make lists with their children.

Write letters to grandparents and other family members still in native country.

Provide print-rich environment in home language and English as much as possible.

Provide experiences of reading and writing for different purposes.

Talk with their children about work, values, religion, and daily activities.

Make learning experiences out of every day activities (sorting mail, sorting socks, shopping with lists, etc.)

Widen their children’s world through learning experiences in the community

(touching animals at the children’s zoo, crunching leaves, taking the bus, etc.)

Take their children to community events and activities designed for families.

Ask their children to tell them what they are learning in the classroom.

Suzanne Wagner

1998

MY GRANDPARENTS MADE IT; WHAT’S WRONG WITH YOU?”

(FACTS ABOUT U.S. IMMIGRANTS AND EDUCATIONAL SUCCESS)

In 1908, in New York City, only 13% of children whose parents were foreign-born went on to high school.

Only 32% of white children whose parents were native-born went on to high school.

Of those who had started high school in New York, 0% of Italian-Americans and

0.1% of Irish-Americans received a diploma in 1911.

Only 20% of the adult population (both immigrant and native-born) had completed high school.

6/30/99

10

Stages of Language Acquisition - Sample Teaching Strategies at Each Stage of

Language Development

Note: The Stages of Language Proficiency were copied from an online tutorial “English Language

Learners: ELLs in the Mainstream”, “Part Two The Theory of Second Language Acquisition” http://www.njpep.org/tutorials/ell_mainstream/part_two/acquisition.html

NJPEP: Virtual Academy, NJ Department of Education, 100 Riverview Plaza, Trenton, NJ 08625-0500

Stage I: Preproduction

Definition : Students at this stage tend to be non-verbal. Most of what is spoken in

English is completely incomprehensible. Students will exhibit some level of frustration, anxiety, and withdrawal, characterized as “culture shock.” Students will focus intensively on listening and viewing what is happening in the classroom. They will copy from the board and repeat what they hear with little or no comprehension at first. Please note:

Students may exhibit inattentiveness at times. However, it should be noted that the language overload of second language learning can be exhausting. Suggestions for the classroom are:

Use of visuals, real objects, manipulatives.

Response through physical movement or manipulation of objects.

Allow students to listen, observe. Do not force students to speak. Provide many listening opportunities.

Group students with more advanced ELLs or cooperative mainstream peers for group activities.

Provide reading materials with simplified text and numerous pictures.

Stage II: Early Production

Definition : Students will begin to repeat language commonly used in social conversation and will be able to use routine expressions. They will make statements and ask questions with isolated words or simple phrases. They will decode according to the phonetic rules of first language. Students can identify people, places, and objects and can participate in class activities by relating information to this type of information.

Students may continue to exhibit inattentiveness at times, but not to the frequency and intensity noted for students at Stage One. Suggestions for the classroom are:

Use simplified, abbreviated text materials, focusing on the main idea[s].

Continue to provide listening activities with visual support.

Begin writing activities, such as dialogue journals for reflection and response to learning materials.

Ask yes/no questions, or questions requiring a 1-3 word response.

Response to assessments can take the form of actions, manipulation of materials and/or simplified response.

Introduction of predictable books with limited words, more pictures and/or graphics for primary age ELLs.

Introduction of structured retelling activities, with the use of physical responses, visuals, manipulatives for primary age ELLs.

Stage III: Speech Emergence

Definition : Students will exhibit increased proficiency in decoding and comprehending second language words and text. Students will begin, with or without phonics instruction, to decode according to second language rules and from expanded experiences with oral interactions and text. Students will demonstrate an increased understanding of conversations, dialogues, simple stories containing a few details and factual or simple procedural information from content area texts. Teachers will note that written expression will include an expanding vocabulary and the emergence of a writing style. Students can edit writing with guidance [e.g. checklists, peer editors, teacher assistance] and will be able to self-evaluate writing. Suggestions for the classroom are:

Develop activities with content and context embedded practice in all four skill areas.

Ask open-ended questions, but provide models for response orally or through word banks.

Shared or partnered reading and writing activities.

Expanded use of predictable books containing more text, with primary-age ELLs.

Use of content area picture books, with expanded text [fiction and non-fiction] to support learning of content [e.g. science and social studies, such as Adler, David

A. A picture book of Sacagawea; illustrated by Dan Brown. New York: Holiday

House, 2000. ISBN 082341485X. A biography of the Shoshone woman who joined the Lewis and Clark expedition. See “Resources” for a short list of other suggested content area picture books.

Expanded writing opportunities in a variety of genres —descriptive, narrative, instructive, etc.

Introduce learning strategies instruction examples. [See CALLA in Part Four.]

Stage IV: Intermediate Fluency

Definition: There is a marked increase in listening, speaking, reading, and writing comprehension and accuracy of response. Students will demonstrate an increased use of strategies for word attack and comprehension of content reading materials. In addition, the student can read and understand a wider variety of genres in literature.

He/she can summarize, make simple inferences, and can use language to express and defend opinions. First language background knowledge and strategies become a

12

resource for the student. Overall, the student, at this stage, can perform well in the classroom, but teachers will need to provide structure, strategies, and guidance.

Suggestions for the classroom are:

Provide guided instruction in the use of reference/research materials for middlehigh school ELLs.

Expand learning strategies instruction.

Provide practice in making inferences from content reading.

Model appropriate language for expressing abstract concepts from content learning by providing students with response “stems .” ( See examples on the site.)

Move toward expanded text reading to include supporting details and extended reading activities.

Expand writing repertoire to include various types of letters, newspaper journalism, and creative writing experiences.

Can begin to work in collaborative groups for content activities.

Stage V: Advanced Fluency

Definition : At this stage of development, the student performs “almost” like a native speaker. He/she can produce language that is highly accurate, incorporating more complex vocabulary and grammatical structure in his/her communicative discourse. The student’s reading interests broaden and he/she can read independently for information and/or pleasure. His/her writing skills are at a near native English level. The student continues to use his/her native language as a source to enhance comprehension of

English. Although most English Language Learners are exited at this level of performance, students may still need a “lifeline” for clarification of new concepts and/or vocabulary. Suggestions for the classroom are:

Continue to build concepts through advanced content area reading.

Continue to expand on learning strategies instruction.

Continue to provide enriched writing activities.

Help to build an expressive vocabulary to match the strength of the receptive vocabulary development.

Work in collaborative groups for content activities.

13

CONTENT INSTRUCTION FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

1.

(Known as Sheltered Instruction and Content-based ESL)

Target the “big ideas” of the content.

Identify main principles, achievable objectives, and key vocabulary.

Align instructional activities to objectives and district and state learning standards.

Locate appropriate materials.

2. Access and build upon students’ prior knowledge.

Connect students’ knowledge and experiences to new lesson.

Get everyone “on the same page”.

Ask appropriate questions to facilitate student interaction about their prior knowledge and experiences.

Use the native language as a tool.

3. Make sure that the new information is comprehensible.

Speak clearly without using the slang or idioms

Model language just above the language competence of the learners.

Retell, clarify, and give examples.

Use visuals, manipulatives, gestures, and hands-on experiences, modeling, and demonstrations.

Move from the concrete to the abstract.

Revisit and review previously taught lessons and vocabulary.

4. Use a variety of literacy and vocabulary activities.

Teach vocabulary before, during, and after reading

Develop comprehension strategies before, during, and after reading.

Improve students’ reading fluency through a variety of approaches

Respond to readings through meaningful writing activities.

5. Organize purposeful interactions.

Utilize peers to facilitate learning and sharing ways of thinking.

Implement paired and buddy reading activities.

Teach through cooperative learning activities.

Encourage native language support from peers and adults.

6. Use fair and appropriate assessment strategies.

Encourage students to creatively use the English language they know.

Be easy on the red pen with emergent English writers, focusing on message rather than form.

Use a variety of assessment strategies tied to instructional strategies.

Use rubrics to compare student performance to objectives and benchmarks

.

7. Provide instruction in a low-risk environment.

S. Wagner, Illinois Resource Center, 1999 References: Collier, 95: Cummins, 94: Peregoy and Boyle, 97:

Richard-Amato, 96: Snow, 92

14

AN OVERVIEW OF TEACHING STRATEGIES

FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS

Second language learners learn their second language from anyone who provides them with an opportunity to develop proficiency in the new language. So whether you’re an

English-as-a second-language (ESL) teacher, a science teacher, or a reading specialist, you can help those students become proficient in English.

NATURAL APPROACH

As the name implies, the Natural Approach (Krashen and Terrell 1981) focuses on developing language skills in a natural context. Students acquire language through interaction in authentic and meaningful learning experiences. Teachers provide input in the target language that students can understand (comprehensible input) and add new learning to that base. The principles behind the Natural Approach are:

1. Comprehension precedes production.

2. Production emerges in stages.

3. A syllabus based on communicative goals is more effective.

4. The student’s anxiety level must be low in order for learning to happen.

The following are some of the strategies that are practiced within the Natural Approach:

Total Physical Response (TPR)

TPR, developed by James Asher (1982), was designed primarily for students in the early stages of language acquisition. Since commands can be made comprehensible to students with very limited langauge, Asher used commands as the basis for TPR. The teacher gives a command, demonstrates the command, and then students respond physically to the command. Because students are actively involved and not expected to repeat the command, anxiety is low, and student focus is on comprehension rather than production. Hence, they demonstrate comprehension before their speaking skills emerge. The imperatives, such as “Bring me the book” or

“Pass your paper to the right,” bring the language alive by making it comprehensible and fun. TPR is a well-known beginning ESL method, but TPR-based activities can be adapted to almost any level and incorporated into mainstream or multi-level classes, particularly in areas where visible directions can be given. TPR also provides a base for literacy development in the second language as students learn to read the commands they followed.

Language Experience Approach (LEA)

The LEA is an effective method to help promote literacy development. Students recount stories based on their own interests and activities, such as a trip, a movie, a story, or a project in which they all participated, and the teacher writes their words.

These student-produced stories are then used for reading material and language development. Application of LEA can be used with many different activities and proficiency levels.

15

Literature-Based Approach

In a literature-based approach, stories and literature are used as the base and context for language learning. This is a valuable means of developing oral language and literacy skills. Pattern books are especially beneficial for younger learners because of rhyme, rhythm, repetition, easily identifiable situations, predictability, high frequency vocabulary, and a strong correlation between the printed text and the use of visuals.

Authentic quality materials should be chosen, with a heavy inclusion of multicultural books. Some children’s literature, such as historical fiction or stories related to social problems can also be used very effectively with older learners.

Use of Graphic Organizers

The use of semantic webs and graphic organizers is a very helpful way for students to simplify the reading and writing process. Besides helping students to plan and organize material, they can also promote insight into cultural variations. As they are used to elicit students’ thoughts and background knowledge, they also help t promote higher-level thinking. Some common examples of graphic organizers are Venn

Diagrams, web diagrams, and story maps.

Use of Cooperative Structures

In cooperative structures, students work together in small groups, dependent on each other to reach goals. These activities are very effective with ESL students because they allow for interaction in a non-threatening situation. Students participate and contribute to the group according to their proficiency levels. Some exampoles that work well in mainstream contentarea classes are “Numbered-Heads-Together,” “Think-

Pair-

Share,” and “Jigsaw.”

CONTENT-BASED APPROACH

According to the most recent research, one of the most effective methods of ESL instruction is the content-based approach, where language instruction is integrated with the content areas. Rather than developing an ESL program that is focused on the language needed for social interactions or the structure of language, this method incorporates language into the context of academic content. The core curriculum is the basis for teaching language. Instructors focus on the key principles and concepts and use visuals, hands-on activities, simpler language, adapted readings, graphic organizers, and so forth to help make the most important academic content comprehensible. Thus, language skills develop as children work on math, social studies, science or language arts at their appropriate age and grade levels.

The examples given in this article are recommended because they work with English language learners. These methods include learning situations that provide for the following critical factors:

Comprehensible input

Low anxiety for the students

Many opportunities for interaction and language use

Meaningful communication and natural language

16

Language-learning situations that are fun and motivational

Development of higher-order thinking skills

In summary, there is not a single correct method to follow in second language instruction. However, when planning lessons and choosing activities, teachers should ensure that the strategies used incorporate the elements most needed by students. It is always important to keep abreast of theoretical concepts and current research in order to develop a personal philosophy and teaching style. Teachers should then vary activities and select strategies according to students’ needs and goals.

References:

Asher, J. (1982). Learning another language through action: the complete teacher’s

Guidebook.

Los Batos, CA: Sky Oaks.

Krashen, S. & Terrell, T. (1983). The natural approach: language acquisition in the classroom.

Engliwood Cliffs, N.T.: Alemany/Prentice Hall.

Beverly Ben-David, 2000. Illinois Resource Center (847)803-3112

SUGGESTED FOLLOW-UP

For resources, related in-district support options, workshops and courses, visit www.thecenterweb.org

and select the Illinois Resource Center or call (847) 577-2748.

The Illinois Resource Center is funded to serve linguistically and culturally diverse learners in Illinois. There is no charge for public schools in Illinois outside of Chicago.

Workshops and courses are open to all interested teachers.

Select Illinois Resource Center (IRC)

Select resources and scroll to recommended materials if seeking materials

Select Ekits for other support resources prepared by the IRC

Select professional links in the sidebar for multiple links and resources

For a copy of the English Language Proficiency Standards for English Language

Learners in Kindergarten through Grade 12 that apply to Illinois go to the online resource at http://www.isbe.net/bilingual/pdfs/elps_framework.pdf

For a four-part tutorial related to serving ELLs in the Mainstream see the online resource developed by the New Jersey Department of Education: New Jersey

Professional Education Port

“English Language Learners: ELLs in the Mainstream” at the following site. http://www.njpep.org/tutorials/ell_mainstream/intro.html

“Part Two The Theory of Second Language Acquisition” is the most applicable to the content of this workshop.

17