Immediacy as Impacted by Race

advertisement

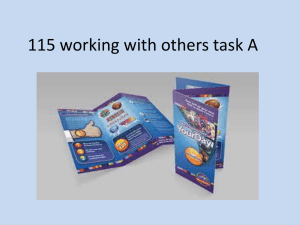

Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 1 RUNNING HEAD: Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race Multicultural Relations in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of College Professor Verbal Immediacy as Impacted by Race Kasey L. Serdar Westminster College McNair Scholars Program Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 2 Abstract As the percentage of minorities enrolled in education increases, it is vital to consider how the racial background of students and teachers impacts students’ capacity to communicate with their instructors. The present study examined whether students’ ratings of professors’ verbal immediacy differed based on both the race of the student, and that of the professor. Twohundred-seventy-eight college students (from White/Caucasian, Black/African-American, and Hispanic/Latino backgrounds) were surveyed about their perceptions of the verbal immediacy of a fictitious professor of a race either congruent or incongruent with their own. Results indicated that students viewed professors of an incongruent race to be less verbally immediate. This difference approached significance at trend level, and was strongest for the Black/AfricanAmerican group. These findings underscore the impact of racial relations and perceptions on interactions in educational settings, regardless of subject content and pedagogical style. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 3 Multicultural Relations in Higher Education: Students’ Perceptions of College Professor Verbal Immediacy as Impacted by Race The connection that develops between teacher and student has been shown to have critical effects on aspects of students’ school adaptation. Individuals’ ability to excel in an academic environment is impacted, at least partially, by the degree to which they are able to form concrete, open relationships with educators. As students progress through school, the academic culture transforms to a more formal, evaluative setting, in which students are expected to live up to strict standards of performance. In the wake of this transforming educational environment, the value of solid teacher-student relationships is not diminished. This is especially true for students from underrepresented minority groups (e.g. Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino), as these groups are not always encouraged to pursue educational goals with significant vigor. As the percentage of minorities enrolled in education increases, it is vital to consider how racial background (of both students and instructors) impacts students’ capacity to relate to and communicate with their instructors. While some research has been conducted to examine how teachers perceive and interact with students from underrepresented racial groups, less research has been performed to explore how multicultural issues affect students’ perceptions of professors. The purpose of the present study is to examine whether professors’ racial background (White/Caucasian, Black/African-American, or Hispanic/Latino) impacts students’ perceptions of verbal immediacy. The study also examines students’ racial background, with the assumption that such factors may affect his or her perceptions of professors of different races. Teacher-Student Interaction Research has indicated that the relationship between student and teacher is one that can have a profound influence on a student’s achievement, motivation, and aspirations for the future. Numerous studies have shown that high quality teacher-student interactions are linked to more Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 4 positive educational experiences for students (e.g. Birch & Ladd, 1996; Wentzel, 1997; Christophel, 1990). Research by Birch and Ladd (1996) demonstrated how the bond between teacher and student is established early in a child’s development, and how such critical connections have the power facilitate healthy adjustment in educational settings. This study hypothesized that students who felt support from adult figures at school (i.e. teachers) would be more likely to display positive adaptation in educational settings. Two hundred and six kindergarteners and their instructors were surveyed about students’ perceived closeness, dependency, and conflict with their teachers. In conjunction, measures were taken to evaluate students’ academic performance, school attitudes, and positive engagement in the classroom environment. Results indicate that closeness between student and teacher was related to students’ increased levels of academic performance. This suggests that teachers are powerful figures in the lives of most children; other studies indicate that when considered in conjunction with peers, parents, and other social influences, teachers have been found to have the most direct influence on children’s interest in school (e.g. Wentzel, 1997). Studies on the importance of the teacher-student connection in childhood (see Birch & Ladd, 1996) have been further developed by research examining the value of the teacher-student relationship in adolescence. As children move through their education, the structure of the school environment transforms from an informal, noncompetitive setting that is normally seen in elementary school, to the more formal, competitive, evaluative structure that is typical of middle school, high school, and college. This structural transformation in the educational environment is also frequently marked by increased reinforcement of extrinsic motivators (e.g. grades) over intrinsic motivators (e.g. personal interest in a topic; Harter, 1996). Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 5 As the academic setting transforms, so too does the relationship of students with their instructors. Teachers are a medium by which the changing attitudes, values, and expectations of the more formalized instructional environment of middle school and high school are communicated (Harter, 1996). In her summary of research about teacher influences on students’ scholastic achievement, Harter (1996) stated, “teachers not only instruct, but serve to represent and communicate a particular educational philosophy, including the standards by which students will be evaluated” (p. 11). As teachers indirectly clarify and enforce the standards of education, students’ perceptions of and relationships with their teachers change. Research has indicated that students perceive teachers to be more evaluative with each increasing grade level (Harter, Whitesell, & Kowalski, 1992). Further, the shift from elementary to middle school has been found to lead students to reevaluate their competence in the new educational setting. In a 7month longitudinal study, Harter, Whitesell, and Kowalski (1992) found that 50 percent of students experienced feeling more or less competent when entering middle school from elementary, while the remaining 50 percent reported feeling relatively stable in their perceptions of competence. Because students come to reevaluate their aptitude upon entering a more formalized academic setting, it seems clear that having encouraging relationships with educators would positively effect adolescents’ educational adjustment. Research supports a relationship between solid teacher-student relationships and students’ positive academic transition in adolescence (e.g. (Wentzel, 1997; Wentzel, 2002). Results of Wenzel (1997) indicate that there is a significant correlation between early adolescent students’ perceptions of their teachers’ level of caring and students’ drive for achievement. The study surveyed 375 eighth grade students (a subset of which were followed for 3 years) about perceived caring they felt from teachers. Results of the Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 6 examination indicate that young adolescent students (sixth to eighth grade) who feel supported by their teachers were more motivated to achieve their goals. Students’ perceptions of being cared for and valued, especially by teachers in a formal classroom setting, prompted students to become more involved in classroom activities. The study also suggested that a solid connection between student and teacher works to enhance students’ development by promoting positive feelings of self worth. Research has also been conducted to explore faculty-student relationships on college campuses. Many of the investigations about the dynamics of teacher-student relationships in higher education have been conducted within the context of verbal and nonverbal immediacy behaviors. Immediacy was originally defined by Mehrabian (1967) as the level of perceived physical and/or psychological closeness between individuals. Based on this construct, research examining teachers’ verbal immediacy has explored vocal behaviors that instructors use to decrease physical and/or psychological distance between themselves and their students (Christophel, 1990; Christophel & Gorham, 1995). Such verbal behaviors would include: addressing students by name, asking open-ended questions of students, encouraging students to talk, having conversations with students before and after class, and soliciting viewpoints from students (Christophel, 1990; Christophel & Gorham, 1995). Similarly, nonverbal immediacy behaviors are non-vocal behaviors that communicate an instructor’s openness and approachability (e.g. smiling, relaxed body position; Gorham, 1988; Christophel, 1990; Christophel & Gorham, 1995). Many studies have shown a positive relationship between perceived instructor immediacy and students’ motivation (Christophel, 1990; Christophel & Gorham, 1995; Richmond, 1990; Frymier, 1994), affective, and cognitive learning (Christophel, 1990; Gorham, 1988; Rodriguez Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 7 & Plax, 1996). Christophel (1990) surveyed undergraduate students about their instructors’ use of both verbal and nonverbal immediacy behaviors, while also administering measures to gauge students’ level of state motivation (engagement in current classroom setting). Results of the study indicated that teachers’ use of immediacy behaviors (both verbal and nonverbal) is positively correlated with students’ state motivation. In addition, this study also found that students’ level of cognitive and affective learning was positively related to teacher immediacy. Gorham (1988) also examined college students’ perceptions of instructors’ verbal immediacy and its impact on cognitive and affective learning outcomes. Results of this research also supported a link between an instructor’s level of verbal immediacy and learning for students. A variety of verbal behaviors, most specifically instructors’ use of humor, praise of students’ work, and frequency of initiating informal conversations with students seem to predict more positive cognitive and affective learning outcomes for students. Research has shown that, in addition to having a positive impact on students’ motivation and learning, instructor immediacy (verbal and nonverbal) is also related to students’ willingness to communicate with faculty members. Jaasma and Koper (1999) surveyed 274 students about both perceptions of instructors’ verbal and nonverbal immediacy and their levels of out-of-class communication with instructors. Findings from the study suggest that frequency and length of students’ out-of-class communication with their instructors was most closely linked to students’ perceptions of instructors’ verbal immediacy. Students spoke more frequently, and for longer periods of time, with professors they perceived to be more verbally immediate than professors they did not feel were verbally immediate. Thus, it seems that verbal immediacy helps students create more open, collaborative relationships with instructors by helping students feel at ease when communicating about various topics. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 8 This line of research has shown that students’ motivation and learning can be altered by student’s perceptions of an instructors’ verbal immediacy. The level of openness an instructor establishes, both inside and outside of the educational setting, can profoundly influence students’ desire to succeed in the course. Students’ perceptions of a professor’s verbal immediacy also influence students’ communication with faculty members, an often essential component to academic attainment. If students are not willing to interact with a teacher because they perceive that instructor to be less approachable and verbally immediate, such restraint could negatively impact students’ capacity to attain success in academic environments. Presence and Achievement of Minorities in Academic Settings It is critical to examine aspects of teacher-student relationships in relation to race, because certain racial groups (i.e. Hispanic/Latino) are among the fastest growing segments of the population of the United States. It is estimated that in 2000, approximately 12.7 % of the United States’ population was Black/African-American, and 12.6% was Hispanic/Latino. These percentages are expected to increase, with population projections estimating that Black/AfricanAmerican and Hispanic/Latino populations will comprise 13.5% and 17.8 % of the United States population in 2020. There has also been increasing representation of students from various racial backgrounds enrolled in higher education in recent years. In 2000, Black/African-American students comprised 14 % of student populations, and Hispanic/Latino students represented 9 % of students on college campuses. Further, statistics indicate that roughly 12 % of college students in the United States are foreign born. These estimates mark a dramatic increase in minority student enrollment when compared to statistics from 1979, when 84 % of college students were from White/non-Hispanic backgrounds, and Black/African-American students comprised only 10 % of student populations (U. S. Bureau of the Census, 2002). Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 9 While there has been an increase in minority populations and underrepresented college student enrollment in the United States, research has indicated that students from certain minority groups still display disproportionately high rates of dropout from academic settings (e.g. Rumberger, 1995; Steele, 1997; Griffin, 2002). For instance, statistics from Kaufman, Alt, and Chapman (2004) indicated that Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino students, ages 16-24, drop out of school at rates of roughly 10.9% and 27%. These rates are significantly elevated when compared to the 7% attrition rate for White/Caucasian students. Further, dropout rates among Hispanic/Latino students are 2 to 3.5 times higher than dropout rates of White/nonLatino students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000). The high incidence of drop is seen for certain groups in both secondary and post secondary education; studies indicate that approximately 62% of Black/African-American college students do not finish their college education as compared to the national dropout rate of 41%. In addition, only 16% of second generation Hispanic/Latino students who graduate high school earn their bachelor’s degree (Hispanics enroll in college at high rates, but many fail to graduate; American Council on Education, 1995-1996). There have been many proposed causes for the higher rates of dropout among students from particular racial groups. Numerous studies have indicated that the interaction of individual and social factors influence minority students’ attrition. In a multilevel analysis of students’ dropping out of middle school, Rumberger (1995) found that students from Black/AfricanAmerican, Hispanic/Latino, and other racial groups dropout of school largely as a result of family characteristics, such as lower socioeconomic status, limited parental academic support, limited parental supervision, and lower parental educational expectations. In addition, it was found that schools with the higher dropout rates educated more students from minority and lower Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 10 socioeconomic backgrounds. Research has also indicated that neighborhood characteristics (Vartanian & Gleason, 1999) and school characteristics (Rumberger, 1995) impact minority students’ likelihood of dropping out of school. Such research reveals that coming from lowincome neighborhoods (Vartanian & Gleason, 1999) and/or being held back in school, showing high rates of absenteeism, misbehavior, and poor academic performance (Rumberger, 1995) are predictive of a greater likelihood of drop out for minority students. Further research has indicated that Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino students’ rate of academic attrition seems to be related to decreased levels of academic identification (degree to which an individual’s self-esteem is affected by academic attainment). Numerous studies have shown that students from such underrepresented backgrounds are more likely to disidentify from academic endeavors than their White/Caucasian and Asian American counterparts. Such disidentification, in conjunction with other factors, provides some explanation for higher rates of drop out among students from these backgrounds. If students do not consider their educational attainment to reflect at least some aspects of their own self-worth, such students may be less concerned about limited achievement in academic settings (Steele, 1992; Osborne, 1997; Griffin, 2002). The Benefits of Concrete Teacher-Student Relationships to Minority Students The establishment of a concrete teacher-student relationship seems to be especially important for students of underrepresented racial backgrounds (i.e. Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino), as such relationships can often serve as a buffer to many of the other obstacles that such students face in their education. One of the major forms of extended teacher-student interaction has come through faculty mentoring of students. Research has shown that mentoring, an act in which a teacher or other role model works to provide “wise and friendly counsel,” is Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 11 relatively effective in helping minority students attain success in academic settings (see Redmond, 1990, p. 188). Studies also indicate that mentoring relationships most often develop informally, in which a mutual bond between teacher and student develops naturally, as both parties grow to know and like each other. While this type of teacher-student interaction is usually less structured than in formal mentoring (students are assigned a faculty mentor), students and professors benefit from informal mentoring because such relationships are usually based on similar interests and needs from both parties (Redmond, 1990). Informal mentoring relationships generally focus on the students’ long-range career aspirations. With the guidance and support that can come from a faculty mentor, students learn skills, behaviors, and attitudes that help them gain accomplishments in the academic realm (Trujillo, 1986). Redmond (1990) summarized the aspects and benefits of mentoring for underrepresented students in academic settings. Mentoring relationships, according to Redmond, address causes of minority student drop out by promoting closer contact between students and faculty, providing intervention when students experience academic difficulty, and by creating a “culturally validating psychosocial atmosphere” (p. 199). Despite evidence that mentoring helps underrepresented students succeed in academic settings, research indicates that the development of mentoring relationships between faculty and underrepresented students are somewhat rare (Blackwell, 1989; Redmond, 1989; Davidson & Foster-Johnson, 2001). Blackwell (1989) found that only one of every eight Black/AfricanAmerican students develops a mentoring relationship with a faculty member as an undergraduate. Further, even fewer (7%) Black/African-American students reported having opportunities to work with professors of the same racial background. While there are many factors that affect the development of mentoring relationships between students and instructors, Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 12 one of the major issues in the development of such critical connections is that the informal relationships are usually established between individuals who feel comfortable with each other (Trujillo, 1986). This reality is problematic for students from minority backgrounds, because such students may not feel as comfortable interacting with White/Caucasian instructors from White/Caucasian backgrounds (Redmond, 1990). Race as a Factor Influencing Student Perceptions of Professors While it seems clear that the teacher-student relationship has at least some impact on individuals’ academic achievement and motivation, it is not clear whether the racial background of both students and their instructors affects the quality and development of such critical relationships. Examination of how multicultural factors affect both students’ and instructors’ perceptions is critical, as such impressions can either foster or impede the establishment of a concrete teacher-student relationship. Some studies have examined how teachers interact with students of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds. Casteel (1998) examined treatment of both White/Caucasian and Black/AfricanAmerican students by middle school White/Caucasian teachers. The study explored many different types of interactions between students and teachers; instructors’ actions such as asking questions, praising, and helping students were observed in the classroom and coded to determine whether the frequency of such interactions differed based on the race of the student. Results of the study overwhelmingly indicate that Black/African-American students are not treated as favorably as White/Caucasian students in classrooms with a White/Caucasian teacher. The research revealed that teachers asked more questions of White/Caucasian students by name (both critical thinking and single answer) than of Black/African-American students. White/Caucasian students were also more likely to be praised after providing a correct answer, and given cues to Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 13 help when struggling with a question than Black/African-American students. Overall, White/Caucasian students in the study were found to receive a greater portion of positive interactions with teachers, while Black/African-American students were more likely to have negative encounters with teachers. Researchers have also tried to explore whether race impacts students’ perceptions of instructors in the classroom. Marcus, Gross, and Seedfeldt (1991) examined fifth-grade Black/African-American and White/Caucasian students’ perceptions of how their teachers treated them. Students of similar achievement levels were given the Teacher Treatment Inventory (TTI), a measure designed to gauge how students interpret their teachers’ treatment of them in the classroom. Results of the study did not reveal a significant main effect of race when examined independently, but significant results were found when race was analyzed in conjunction with gender. The group of students in the study that reported the most negative perceptions of teacher treatment was the Black/African-American male subgroup; such students reported feeling that teachers treated them as if they were lower achieving students. Black/African-American males were more likely to report that teachers held lower expectations for them and did not trust their actions in the classroom environment. They also reported feeling that teachers called on them less frequently for answers to questions. These results were not true for White/Caucasian male subgroup, thus indicating that such significant results are not simply an effect of gender. Rather, the study suggests that race may interact with other factors (e.g. gender, social class) to affect the way students perceive teachers in the classroom. Findings of the previous study are supported by Casteel (1998) which also indicated that Black/AfricanAmerican boys were treated more negatively by teachers than their White/Caucasian counterparts. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 14 Limited research has been conducted to examine how racial background (of both students and professors) impacts students’ perceptions of instructors’ verbal and nonverbal immediacy. One study done by Neuliep (1995) examined both Black/African-American and White/Caucasian students’ perceptions of immediacy of professors of the same race. The study also examined students’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning outcomes. The results of this study indicated that Black/African-American students perceive Black/African-American teachers to be more immediate than White/Caucasian students perceive White/Caucasian instructors to be. It was also found that teacher immediacy operates differently for students from Black/AfricanAmerican and White/Caucasian backgrounds, as there was a stronger connection between White/Caucasian students’ ratings of teacher immediacy and cognitive learning. Thus, White/Caucasian students felt they would learn less in a class with a less immediate instructor, while the Black/African-American students did not perceive that lower levels of immediacy would negatively impact their learning. Further, results of the study indicated that White/Caucasian students were more likely to associate immediacy with positive attitudes about instructors, course content, and enrollment in another course with the same instructor. Rucker and Gendrin (2003) further modified Neuliep’s (1995) research by examining how students’ racial identity influences their perceptions of Black/African-American and White/Caucasian instuctors’ verbal and nonverbal immediacy. The study examined 239 students from Black, African-American, African Hispanic, and Caribbean Black racial backgrounds, taken from a historically Black college. Results indicated that students felt stronger identification with Black/African-American instructors than White/Caucasian instructors when examining verbal immediacy and black identity. These findings suggest that not only do Black/African- Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 15 American students perceive professors of a similar racial background to be more open, approachable, and immediate, but also that they are more likely to identify with such professors. Overview of the Present Study While investigations conducted by Neuliep (1995) and Rucker and Gendrin (2003) are certainly critical additions to studies examining teacher immediacy, further research exploring the construct of immediacy in relation to race is warranted. Both of the previous studies have primarily examined students’ perceptions of immediacy of a professor of the same racial background; limited attention was given to students’ perceptions of instructors from a different racial backgrounds. Further, both studies examined only Black/African-American and Caucasian American students’ perceptions, thus, such results give no indication of how other racial/ethnic groups (e.g. Hispanic/Latino) perceive professors of both the same and different racial backgrounds on teacher immediacy. The present study sought to examine whether the racial background of both the student and professor impacts students’ perceptions of college professors’ verbal immediacy. It was hypothesized that students would perceive a professor of a different race to be less verbally immediate than a professor of the same race. This hypothesis was formulated based on conclusions of previous research examining students’ perceptions of teacher treatment (Marcus et al., 1991) and immediacy (Neuliep, 1995; Rucker & Gendrin, 2003) as affected by race. Another paradigm that indicates that individuals would rate professors of the same race to be more verbally immediate is the cultural contracts theory. This theory attempts to explore interracial relations, emphasizing how connections between people of different cultures influence individuals’ identity formation. On of the main arguments of this theory is that individuals interact with people from similar racial/ethnic backgrounds in order to maintain and confirm Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 16 their own identity (Hendrix, Jackson II, & Warren, 2003). Thus, it seems logical that students would want to approach professors of a similar racial background, because in doing so, they would be establishing their sense of self. This inclination may lead students to rate instructors of the same race higher on measures of verbal immediacy than professors of a different race. The study is valuable because a student’s perceptions of instructors’ verbal immediacy have an impact on whether that student will approach such instructors for help and guidance. If minority students perceive White/Caucasian professors to be less verbally immediate, they may be less likely to seek their assistance than a professor from the same racial/ethnic background. Such avoidance could have a critical influence on underrepresented students’ levels of achievement, since research on instructor immediacy has shown that perceived immediacy is related to greater motivation and learning from students (Christophel, 1990). This issue is especially vital in educational settings where minority students are exposed almost exclusively to White/Caucasian instructors, because such students may not have access to same race instructors with whom they may feel more comfortable seeking guidance from. Methods Participants The present study consisted of 278 participants who were divided into groups on the basis of racial/ethnic background (159 Caucasian, 24 African American, and 39 Latino). These groups were then separated into subgroups based which tutorial they would be exposed to. Data from 56 participants was dropped from analysis because such individuals did not match the targeted racial/ethnic background, leaving a total of 222 participants whose data was analyzed. Individuals were selected from 3 institutions of higher education in the western United States (one small liberal arts college, one large research-focused university, and one large community Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 17 college) and were recruited both informally on each campus and through flyer distribution. Students were also gathered with assistance of the Student Support Services (SSS) Programs at two of the campuses, and the Center for Ethnic Student Affairs at the large research-focused university. Individuals eligible to participate in the study were limited to college students enrolled within 12 months of administration of the tutorial and survey. Students had an age range of 18 years of age to late adulthood. Individuals were offered incentives (gift certificates) for participating in the study. Materials Three versions of an online tutorial were created for the current study. All tutorials were identical in content, vocal delivery (professor’s voice), structure, and tone, and each tutorial was created and administered through the same online WebCT course created for the study. WebCT is educational software designed to provide course content to students through an online collaborative environment. Students in WebCT courses are able to access educational materials posted through the login on their educational institution’s website. This software was chosen as a mode of administering the tutorial because it could be easily accessed on different college campuses. Versions of the tutorial differed only by the photograph of the fictitious professor (displayed on every slide) and the professor’s name (displayed on the first slide only). Each of the tutorials contained a photograph of a professor (shown in the upper right hand corner) of a specified ethnic/racial background (Hispanic/Latino for Tutorial 1, Caucasian for Tutorial 2, and Black/African American for Tutorial 3). The tutorials also differed by the name displayed on the first slide; names were chosen that emphasized the professor’s ethnic/racial background. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 18 Each tutorial was titled “The Time Value of Money,” and the information presented explained the concept and application of compound interest on personal finance. Content material of the tutorial was developed through investigators’ collaboration with the director of the Center for Financial Analysis at the small liberal arts college. Information about the topic was adapted from material presented in Keown, Gardner, Torahzadeh, and Dixon (1995-2004). The topic was selected because it is relatively neutral and had the greatest application for students from different areas of study. The script for the tutorial was modified by investigators after pilot testing to ensure that the tutorial would be engaging enough to withhold participants’ attention. Each tutorial was created from a Microsoft Powerpoint Presentation, which was then converted into a Quicktime movie and imported into the WebCT course. The information presented on the slides of the tutorial reinforced and expressed visually (through graphs and figures) auditory information. Several different narrations (one of which was used for all three versions of the tutorial) were recorded through Audacity (an audio recording and editing program) to represent the voice of fictitious professor displayed each version of the tutorial. Such narrations were piloted, and the most neutral voice was selected for use in the study. Efforts were made to obtain a voice that sounded congruent with the racial background of all three of the professors depicted. Pictures similar in background, size, and detail were obtained to represent professors in each version of the tutorial. Procedures The present study was designed and conducted as part of another study performed by Chavez and Ferrin (2005), examining the influence of race on students’ perceptions of professor credibility. Individuals asked to participate in the research were told that the study was Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 19 evaluating “the effectiveness of classroom instruction.” Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Individuals were alternately assigned to view one of the three tutorials by the researcher, based on the researchers own perception of the student’s racial background. Based on this assignment, participants’ racial background was considered to be either congruent or incongruent with the racial background of the professor displayed in each tutorial. Caucasian participants viewed either tutorial 1(depicting a Hispanic/Latino professor), tutorial 2 (depicting a White/Caucasian professor), or tutorial 3 (depicting a Black/African-American professor). Hispanic/Latino participants watched either tutorial 1 or 2, and Black/African American participants viewed either tutorial 2 or 3. Participants were given identical instructions about how the tutorial would be administered. After the researcher logged them into the WebCT course and set up the tutorial and evaluation in separate windows, students viewed the tutorial. The tutorials were set up on designated computers at the libraries of all 3 institutions, the student union of 2 of the institutions, and the SSS building of the large community college. Participants heard the audio through a set of headphones connected to each computer. After viewing the tutorial, researchers instructed participants to navigate to a questionnaire intended to gauge students’ perceptions of the tutorial. Measures Participants completed a two-part, 39 item questionnaire (including questions from the other study being conducted) through a link in the online WebCT login. The first part of the questionnaire contained background information, including questions regarding age, gender, class standing, grade point average, racial/ethnic background, English proficiency, length of United States residency, and preferred mode of contacting professors (by email, phone, or in person). The second section of the survey, which consisted of five questions (excluding Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 20 questions used for the other study; see Appendix A), measured students’ evaluations of the fictitious professor’s verbal immediacy based on their impressions from the tutorial. Verbal immediacy questions were formulated and modeled after measures used in Christophel (1990), Gorham (1988), and Christophel and Gorham (1995). Questions were presented as statements, to which students would respond on a likert scale, ranging from (1) Strongly Disagree to (5) Strongly Agree. Results Independent samples t-tests were performed and revealed no significant main effect of race congruence on combined target groups’ ratings of congruent and incongruent professors’ verbal immediacy. When analyzed separately however, independent samples t-tests revealed an effect of race (t(24)=1.752, p=.093) for the Black/African- American group, such that Black/African-American participants were likely to rate the professor of an incongruent race to be less verbally immediate than a professor of a congruent race. This difference approached significance at trend level. In addition, no significant differences were found for Hispanic/Latino and White/Caucasian groups’ ratings of congruent and incongruent professors on perceptions of verbal immediacy. These results are represented graphically in figure 1. Insert Figure 1 here Discussion The purpose of the present study was to expand upon research about teacher immediacy by evaluating whether students’ perceptions of professors’ verbal immediacy are impacted by the racial background of both the student and college professor. It was hypothesized that students Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 21 would evaluate a professor of an incongruent racial background to be less verbally immediate than a professor whose racial background was congruent to that of the student. Results of the study partially supported the initial hypothesis, as there was a trend toward significant differences for the Black/African-American target group in their ratings of verbal immediacy for professors of a congruent versus an incongruent race. The study indicated that race (of both student and professor) may have some impact on students’ perceptions of a professor’s verbal immediacy. The Black/African-American students in the study were found to evaluate the Black/African-American professor to be more verbally immediate than the White/Caucasian professor. While these results were not statistically significant, the findings did constitute a trend toward significant differences. It is possible that with an increased sample size of Black/African-American participants, differences may be more substantial. Results of the study did not indicate significant differences for the White/Caucasian and Hispanic/Latino students’ ratings of professors of a congruent and incongruent racial background. Thus, it cannot be inferred from this research that a race differential between student and professor impacts students’ perceptions of professors’ immediacy for all racial groups. Findings from the present study partially support results of Neuliep (1995) and Rucker and Gendrin (2003) regarding students’ perceptions of verbal immediacy of professors of a congruent and incongruent race. Confirming previous research, Black/African-American students had a tendency to rate Black/African-American professors to be more verbally immediate than White/Caucasian professors. However, it was not found that Black/AfricanAmerican professors were rated to be more verbally immediate by Black/African-American students than White/Caucasian professors when rated by White/Caucasian students, as was indicated in Neuliep (1995). Further, the study supports the findings from Rucker and Gendrin Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 22 (2003) that Black/African-American students identify more with instructors from the same racial background. The results of the present study also confirm previous research indicating that students perceive professors differently based on racial background (Marcus et al., 1991). As previous research indicated, Black/African-American students’ perceptions of professors of an incongruent race seem to be colored by their own cultural background, in that such students felt less comfortable approaching a professor of a White/Caucasian background. This notion was not confirmed for the Hispanic/Latino and White/Caucasian groups with respect to instructors’ verbal immediacy, however, so it cannot be assumed that cultural or racial background influences the perceptions of all students. The present study has many valuable implications for current research on the influence of teacher immediacy, as it examines this construct in relation to both students’ and professors’ racial background. One of the most powerful inferences that can be drawn from this research is that the racial background of a professor may impact Black/African-American students’ perceptions of that professor’s verbal immediacy. An instructor that is, in reality, very approachable and verbally immediate, may be perceived to be less verbally immediate by students from an incongruent racial background. Further, the study indicates that race may be barrier to the development of a collaborative and constructive teacher-student relationship. If students perceive a professor to be less approachable, it is unlikely that such students will seek guidance and support from that professor. This reluctance hinders the development of critical connections with instructors that could help a student attain success in an academic milieu. There are many important limitations to note when considering application of the findings of the present study. While the sample size was relatively large for the White/Caucasian subgroup, the sample sizes for the Hispanic/Latino and Black/African-American subgroups were Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 23 relatively small, which may have limited the statistical power of the data set. The sample was also taken from a relatively non-diverse area (as compared to other regions of the country). Thus, results cannot necessarily be generalized to populations in other geographical areas. Further, because this study was conducted on the computer and not in an actual classroom environment, it cannot be assumed that student evaluations of verbal immediacy of the professor in the computer experiment would be the same if students were in an interactive class. Future research should focus on replication of the present study, in which the sample size for the Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino target groups should be increased. Studies could also examine students’ perceptions of professors’ verbal immediacy in relation to other racial/ethnic groups (e.g. Asian, Pacific Islander), not examined in this research. Expansion in such directions would be valuable because different racial/ethnic groups have diverse experiences and perceptions; it can not be assumed from the current study that all races perceive professors’ verbal immediacy similarly. Further, it may be valuable to examine students from mixed racial/ethnic backgrounds, as it is likely that these individuals will not identify solely with one particular racial category. Studies could also focus on students’ from other geographical regions, in which there are different concentrations of racial populations than examined in the present study. It would be valuable to compare samples from different areas of the country (e.g. northeast vs. southwest), because doing so would provide a more comprehensive examination of how perceptions of verbal immediacy vary from region to region. Further, it may also be beneficial to measure the level at which students’ from certain racial/ethnic groups identify with their cultural background, to see if that level of identification affects students perceptions of verbal immediacy. Other valuable expansions of this study could focus on gender, and whether the interaction of race and Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 24 gender affects students’ perceptions. It may also be interesting to explore whether professors and students from varied academic backgrounds (e.g. natural sciences, business, social sciences) hold different perceptions of verbal immediacy, to determine whether type of educational background impacts perceptions of verbal immediacy. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 25 References Casteel, C. A. (2000). African American students' perceptions of their treatment by Caucasian teachers. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 27(3), 143. Christophel, D. M. (1990). The relationships among teacher immediacy behaviors, student motivation, and learning. Communication Education, 39(4), 323. Christophel, D. M., & Gorham, J. (1995). A test-retext analysis of student motivation, teacher immediacy, and perceived sources of motivation and demotivation in college classes. Communication Education, 44(4), 292. Blackwell, J. E. (1989). Mentoring: An action strategy for increasing minority faculty. Academe, 75(5), 8-14. Davidson, M. N., & Foster-Johnson, L. (2001). Mentoring in the preparation of graduate researchers of color. Review of Educational Research, 71(4), 549-574. Frymier, A. B. (1994). The use of affinity-seeking in producing liking and learning in the classroom. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 22(2), 87. Gorham, J. (1988). The relationship between verbal teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning. Communication Education, 37(1), 40. Griffin, B. W. (2002). Academic disidentification, race, and high school dropouts. High School Journal, 85(4), 71. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 26 Harter, S., Whitesell, N. R., & Kowalski, P. S. (1992). Individual differences in the effects of educational transitions on young adolescents' perceptions of competence and motivational orientation. American Educational Research Journal, 29(4), 777-807. Hendrix, K. G., Jackson II, R. L., & Warren, J. R. (2003). Shifting academic landscapes: Exploring co-identities, identity negotiation, and critical progressive pedagogy. Communication Education, 52(3/4), 177-190. Hispanics enroll in college at high rates, but many fail to graduate.(2002). Black Issues in Higher Education, 19(16), 9. Jaasma, M. A., & Koper, R. J. (1999). The relationship of student-faculty out-of-class communication to instructor immediacy and.. Communication Education, 48(1), 41. Marcus, G., Gross, S., & Seefeldt, C. (1991). Black and white students' perceptions of teacher treatment. Journal of Educational Research, 84(6), 363-367. Mehrabian, A. (1967). Attitudes inferred from non-immediacy of verbal communications. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 6(2), 294-295. Neuliep, J. W. (1995). A comparison of teacher immediacy in african-american and euroamerican college classrooms. Communication Education, 44(3), 267. Osborne, J. W. (1997). Race and academic disidentification. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 728-735. Redmond, S. P. (1990). Mentoring and cultural diversity in academic settings. American Behavioral Scientist, 34(2), 188-200. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 27 Richmond, V. P. (1990). Communication in the classroom: Power and motivation. Communication Education, 39(3), 181. Rodriguez, J. I., & Plax, T. G. (1996). Clarifying the relationship between teacher nonverbal immediacy and student cognitive learning: Affective learning as the central causal mediator. Communication Education, 45(4), 293. Rucker, M. L., & Gendrin, D. M. (2003). The impact of ethnic identification on student learning in the HBCU classroom. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 30(3), 207-215. Rumberger, R. W. (1995). Dropping out of middle school: A multilevel analysis of students and schools. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 583-625. Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613-629. Trujillo, C. M. (1986). A comparative examination of classroom interactions between professors and minority and non-minority college students. American Educational Research Journal, 23(4), 629-642. Vartanian, T. P., & Gleason, P. M. (1999). Do neighborhood conditions affect high school dropout and college graduation rates? Journal of Socio-Economics, 28(1), 21-41. Wentzel, K. R. (2002). Are effective teachers like good parents? teaching styles and student adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 73(1), 287. Wentzel, K. R. (1997). Student motivation in middle school: The role of perceived pedagogical caring. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 411-419. Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 28 FIGURE CAPTION Figure 1. Mean student ratings of congruent/incongruent professor immediacy by racial/ethnic group Perceived Professor Verbal Immediacy and Race 29 Mean Student Perceptions of Professor Immediacy FIGURE 1 Race Congruence between Professor and Student 5.00 Congruent Incongruent 4.00 3.00 2.00 1.00 0.00 White/Caucasian Black/African American Hispanic/Latino Racial/Ethnic Background