here - BCIT Commons

advertisement

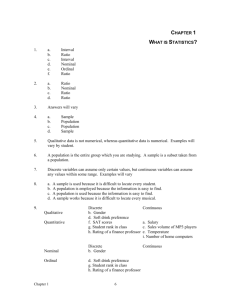

MATH 2441 Probability and Statistics for Biological Sciences Types of Data Statistics deals with the organization, summarization, and analysis of the implications of experimental observations or measurements. How these operations are carried out, and what sort of mathematical methods are appropriate depends on the nature of the observations. Although most of what is mentioned in this document is "common sense", it is important to be aware of the issue. Whenever we make a measurement or an observation, we are measuring or observing something. In statistics, that "something" is called a variable, because different measurements or observations of its "value" may be different -- they may vary over a set or range of possibilities. There are at least three important ways to classify different types of data in statistics. First, there is the distinction between qualitative data and quantitative data: the term qualitative comes from the word "quality", indicating a property, characteristic, feature or attribute. Qualitative data is always a list of words or names of a characteristic. Examples of qualitative variables (which have qualitative "values") are the flavor of ice cream, the color of a person's eyes or hair, the species of a selected life form, the brand of potato chip selected by a customer, the presence or absence of a particular genetic feature, etc. the term quantitative comes from the word "quantity", indicating amount, measure, number, size, etc. Quantitative data is always a list of numerical values where the numbers are more than just names, but actually represent measured numerical values. Examples of quantitative variables that might be considered in studying the population of BCIT students are the height of a student, the age of a student, the number of apples the student ate in the past week. However, the student ID number is a qualitative variable rather than a quantitative variable, since it is in some way equivalent to a name for that student. The numerical digits in a student number are not intended to indicate the measure or size or amount of something that that student has. Sometimes numerical digits are used to represent qualitative values. Thus, the players on a sports team often have numbers on their shirts, but these numbers are qualitative labels, not quantitative values. Similarly, statisticians sometimes code qualitative values with numerical digits -- for example, letting the numerical digits 0 and 1 stand for the qualities "male" and "female", respectively. Grey areas can arise. For example when we use a scale of 1 - 5 to represent the range of responses to questions from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree" on survey-type questionnaires, one could regard the result as qualitative (ie., one of the list of "strongly disagree", "disagree", "no opinion", "agree" or "strongly agree") or as qualitative (the values 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 measuring the degree of agreement with the statement given). Arithmetic operations often make sense with qualitative data, but do not make sense with qualitative data. Secondly there is the notion of scale, of which statisticians distinguish four kinds: nominal scales: the observation of the variable results in one of a set of characteristics or attributes, rather than a numerical value. The word "nominal" comes from the word "name", meaning that the observations will be names rather than numerical values. Nominal scales result in qualitative data. Examples of nominal scales are: flavor (for example, the choice of ice cream purchased by a randomly selected customer might be chocolate, vanilla, strawberry, etc. There is no numerical or quantitative relationship between these flavors: we can't say that vanilla is twice as much as chocolate or that vanilla is five more than chocolate, etc.) gender (possibilities usually are just "male" or "female") David W. Sabo (1999) Types of Data Page 1 of 3 species or variety (if we're talking about, say, lettuce plants, the observed variety might be romaine, buttercrunch, iceberg, leaf, etc.) genetic phenotypes Although people sometimes use numerical codes to label such attributes (for example, we might record ice cream flavors as 1 = chocolate, 2 = vanilla, 3 = strawberry, etc.), these numerical codes are still just names, not values. We know this is so, because in this particular example, it makes no sense to talk about flavor 2.5 being halfway between vanilla and strawberry, for instance. Nominal scales have no natural ordering from least to greatest, or smallest to biggest, or even some intrinsic notion of first to last. ordinal scales: the possible observations of the variable form a set which has a natural order -- the observations can be ranked in some order. Ordinal scales can result in either qualitative or quantitative data. Purely ordinal scales are not as common in technical applications as the other three because usually, the natural order is a result of numerical value, and so the data really belongs to the last two types described below. However, a couple of simple examples of an ordinal scale are: alphabetic order sets of levels (for example, a school student is classified as being in grade 1, or grade 2, or grade 3, etc. There's no implication that a student in grade 2 knows twice as much stuff as a student in grade 1 (though it is true that a student completing grade 2 has completed one grade more than a person completing grade 1, and so in this sense, the grade level completed can be regarded as an interval scale). However, there is a notion of increasing knowledge and skill as one progresses from one grade to the next through the system.) numerical categories (for example, rather than record the actual weight gain of mice on a particular diet -- which would result in a ration scale, see below -- we might simply categorize the observations as weight loss, no change, small gain, moderate gain, and large gain. These five possibilities represent an increase amount of weight gain, but only indicate relative ranking, not precise relative size.) rating scales (you see these in surveys where you are asked to select responses to a sentence from the set of strongly disagree, disagree, no opinion, agree, strongly agree, etc.) Ordinal scales are most often used in biological applications when it is not possible or feasible to work with either an interval or a ratio scale, but the data reflects some sort of ordering or size property. interval scales form the first of two distinctly numerical or quantitative scales. In an interval scale, differences between observed values have significance, but their ratio does not. Another way of saying this is that interval scales do not have a true zero. Examples of interval scales are: the celsius (or fahrenheit) temperature scales. A temperature difference between 40 0 and 200 is the same as the temperature difference between 700 and 500 (for example, it would take as much heat to raise the temperature of some water from 20 0 to 400 as it would to raise the temperature of that water from 50 0 to 700). However, it does not make sense to speak of 400C as being twice as hot as 200C. Nor does it make sense to talk of a temperature of 00C indicating the absence of temperature or the absence of heat. time scales are interval scales. ratio scales are interval scales that also have a natural zero, so that ratios of values (and not just differences between values) are meaningful. Examples are: concentrations (a 2 M solution is twice as concentrated as a 1 M solution. A 0 M solution indicates a solution containing no solute.) measurements of size relative to some standard (for example, measurements of length in meters. A plant 1.5 m tall is twice as tall as a plant which is 0.75 m tall. A mouse which weighs 36 g is twice as heavy as a mouse which weighs just 18 g.) Like interval scales, ratio scales are always numerical. In brief summary, we can say: Page 2 of 3 Types of Data David W. Sabo (1999) a nominal scale consists of an unordered set of qualitative "values" an ordinal scales looks like a nominal scale, but with the possible "values" having a meaningful or natural ordering from first to last, or least to greatest, etc. an interval scale looks like an ordinal scale (has ordering), but with the differences between possible values also being meaningful a ratio scale looks like an interval scale, but with the ratios of possible values also being meaningful. Thirdly, when dealing with quantitative data or variables, it will be necessary to distinguish between discrete and continuous data, and their corresponding variables. the possible values of discrete variables form a set of distinct, isolated quantities. Observations that result from counting objects or items give discrete data, since only whole number values can arise. Thus, the number of "heads" observed when a coin is flipped four times is a discrete quantity, because the only possible values that can arise are 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4. The number of mice in a sample of six which have a certain genetic mutation will be a discrete value, since the only values that can arise are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. the possible values of a continuous variable form an unbroken set of decimal values, with at most a finite number of distinct gaps. Continuous variables usually result from measurements made relative to a standard scale of size: for example, length, mass, time, temperature, etc. Thus, the mass of a mouse selected at random is a value from a continuous scale, since in principle, any value between 0 g (a very light mouse!) and some maximum value could occur. The distinction between discrete and continuous variables is quite important from a methodological point of view. Methods for solving problems involving continuous variables almost always are based on concepts from calculus, whereas methods for solving problems involving discrete variables often just involve simple arithmetic or algebra. Both discrete and continuous variables arise in biological sciences applications, though continuous variables are quite a bit more common. David W. Sabo (1999) Types of Data Page 3 of 3