Online Orientation Programs for New Students

Online Orientation Programs for New Students

For submission to PACRAO April 2006

By Kristen Labrecque

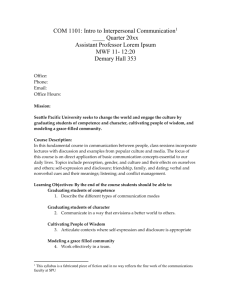

The SPU Vision

“At Seattle Pacific University (SPU), we are committed to engage the culture and change the world through Christian higher education. This is our institutional vision and our promise. We do this by graduating people of competence and character, by becoming people of wisdom who can speak to the culture, and by modeling grace-filled community.” (Gilnett, 2006). In

Student Academic Services, we strive for excellence in the services we provide to the community of students, faculty, and staff who benefit from our work. With the emergence of online learning, we sought to develop an online orientation program for new students. By doing so, we were able to:

Increase student awareness of higher education vocabulary and our institution’s lingo;

Prepare students for their advising appointments, allowing for in-depth conversation, and reducing the amount of time needed for each advising session;

Prepare students for their initial registration by having them take placement tests beforehand, allowing them to register for the appropriate level of classes;

Familiarize students with the online learning environment utilized at SPU.

These preparatory measures ultimately help ease the student’s transition from high school to college, giving them vital information and tools to increase the possibility for success after college entrance. Thanks in part to online learning, we are enrolling some of the most academically prepared students in SPU history.

The emergence of online learning

Growth and change are signs of life—people grow, plants grow, ideas grow—and education is certainly alive and kicking!

But just as people, plants, and ideas need to be nurtured and fostered to grow and change for the better, educational activities and the learning process need attention also. The very nature of human growth and development suggests that learning is constant, and as such, the ways in which educators encourage learning need to grow and change along with the needs of learners. When one commits to the education profession, one has decided to constantly subject one’s self to change. Educators need to be constantly aware of the changes taking place and to develop programming that meets the

needs of those who are teaching as well as those who are learning. An area moving steadily to the forefront of professional development for educators is educational technology.

It should come as no surprise that education has been affected by the rapid development of technology, since the growth of technology has impacted society as a whole. With the introduction of online learning, it would be short-sighted to assume that traditional methodologies will match their previous effectiveness in this new, non-traditional format. According to Hiltz and Turoff (2005), “Online learning is the latest in a long list of social technologies that have been introduced to improve distance learning by adding various augmentations, substitutions, or blending of new pedagogical approaches...” (p. 59).

These augmentations, substitutions, and additions require extra work from the educator, so to invest the time needed in this new format, educators need to see the benefits of online learning in order to make the investment worthwhile.

Aside from the geographical benefit of being able to reach students regardless of time and space, there is the economic factor, which implies that adaptation is not a luxury to consider, but a requirement for survival. “Once most courses are available in digital formats as well as on campuses, geographic monopolies and barriers that have sustained thousands of different colleges and universities in the U.S. and around the world will weaken” (Hiltz and Turoff, 2005, p. 62). Students who, in the past, have made college decisions based on geography will have the freedom to choose the best course or curriculum—not just the best of what is offered in their desired location. Aside from physical geography, students can, regardless of time and space constraints, choose courses whose flexibility caters to them (Hiltz and Turoff, 2005). Online learning combines the needs of the distant learner with the dynamics of traditional face-to-face instruction. As educators adapt and discover successful delivery methods for online instruction, we are able to reach a broader audience.

Online delivery of concepts essential to students’ success

Teachers in various disciplines have already found success using online learning as an instructional delivery method. At

Seattle Pacific University, students can earn credit for courses taken completely online or via classes that are a blend of both face-to-face instruction and online course components. Since students are earning credits and learning subject material by means of this new educational technology, it is not too far reaching to attempt delivery of administrative and process-related instruction as well. In an article titled “Your College Checklist” students are encouraged to “attend freshman orientation to learn about registration, how to get the most from your advisor and professors, and where to go for help” as part of being academically prepared (Mudore, 1999, p. 21). These concepts, essential to students’ success, along with policies and procedural information concerning degree requirements can be delivered via an online learning format to reach students before they even reach your door.

A student’s academic preparedness affects his or her college success, and college success is not just about what is learned in the classroom. Success is also about the development of life skills such as the knowledge of requirements, policies, and procedures, and seeking out of available resources. In addition to the educator’s innate desire to see students succeed,

Parker (1997) claims that we can positively affect retention rates by implementing orientations to help make students aware of what will be required of them and of the support services available to help them through those requirements. Awareness is freedom. By giving students the knowledge they need to succeed, we free them to become responsible for their education and to take ownership of their college experience. The earlier we foster this awareness, the more successful students become. And students who are successful rarely drop out.

As advisors, the benefits of using online instruction as an administrative tool are more immediate. For example, when a student is prepared for an advising appointment, the appointment tends to run more efficiently. In 2004, we tried using an online orientation to degree requirements for students whose initial advising and registration appointments took place over the phone. The time spent on those appointments was cut in half. Conversations that had previously lasted forty-five minutes to an hour now took twenty to thirty minutes. The bottom line was that students who received the information in advance were ready to jump into the scheduling portion of advising and registration—they could almost advise themselves.

Developing the online orientation program

Creating an online orientation program does not have to be a daunting task. By utilizing the online learning environment

SPU uses for regular courses, we were not only able to benefit from the help of our colleagues in Instructional Technology

Services, but we also, as a result of using the pre-existing online tools, were able to prepare our students for the online learning environment they would face as regular SPU students. Because SPU uses Blackboard, we were able to look at existing courses and then determine which tools would be helpful for our purposes. Choosing the tools we would use and modifying them for our purposes, we built our own “course”—the online orientation program we introduced to new students as a required tutorial for their advising and registration appointments.

Requiring students to complete tasks before enrolling them could have been problematic. But because students at SPU are assigned e-mail addresses and Blackboard usernames upon admission, the process of enrolling students in the tutorial was made simple. Communicating with students via their existing e-mail addresses, phone, and mail, we made completion of the tutorial a prerequisite for the upcoming quarter’s registration. This way we could control a student’s awareness of their degree requirements and their readiness for in-depth advising instead of having to start from scratch. We found that students who completed the tutorial successfully were ready to talk about the nuances of their degree requirements (i.e., which major courses also fulfill general requirements) and were more familiar with terminology that is both general (higher education vocabulary) and specific (SPU vocabulary). In addition, we added placement tests for courses in Chemistry and the Foreign Languages so that students would be ready to register for the appropriate class during their initial advising and registration appointment. This helped the students to iron out the details of their schedule, and also helped our enrollment management staff to determine where the most faculty and course offerings were needed. The benefits far outweighed the time required to create and implement the online orientation program for these new students.

New students received communication in the mail and over the Web in order to ensure that they had all the tools necessary to complete the tutorial. Upon successfully logging in to the SPU online learning environment (Blackboard), they saw that they were enrolled in the course “Earning Your Undergraduate Degree at Seattle Pacific University.” Once they selected the course to enter its site, students were welcomed with the following message:

Having the SPU Undergraduate Catalog online was also quite helpful. Students had access to literally everything they needed from our web site.

After reading the announcement (welcome message), students were instructed to navigate through the menu on the left side bar. By clicking on “Course Information” students found a syllabus which outlined the steps necessary for completing the tutorial.

By clicking “Staff Information” students could access contact information for the Undergraduate Academic Counselors at

SPU and get to know the person they would be working with once they reached campus.

The “Course Documents” section is where the instructional materials for students are found. Students access a presentation on SPU’s degree requirements, a test which checks how well they retained the information from the presentation, and the placement tests for Chemistry and Foreign Language which help the students plan their first quarter schedule. In addition, we were faced with new legislation that required all students offered campus housing to acknowledge receiving information regarding meningococcal meningitis. By building those documents into the tutorial we created a verification site where students were required to acknowledge that they had received the information. All test scores were entered into the database and the placement test scores were used as prerequisites for the respective courses. Students who did not complete the section regarding the meningitis information, had a registration hold put on their account. In addition, counselors and advisors could access a student’s results on their degree requirements concept assessment to offer more help and further advising to ensure that the concepts would be learned and retained.

Our online learning environment also provided us with a Discussion Board which we found quite helpful since students frequently had the same questions By answering one person’s question we could answer others’ as well. Staff took turns monitoring the Discussion Board which helped provide a fast turn-around time that students appreciated. In addition, it was helpful for these first-time students to know that they were not alone—many others had similar questions and concerns— and the anonymity allowed by an online post to the Bulletin Board seemed to have encouraged more questions.

By providing this online orientation, we helped new students with their transition process. When students enter college, whether as a first-time freshman or as a college transfer student, they are bombarded with information and could easily feel overwhelmed. Carpenter, Brown, and Hickman (2004) identify the provision of and access to online learning opportunities

as essential to student success because they will prepare students for their academic experience. The more prepared a student is for what they are facing, the less anxious they should be. By providing online learning opportunities in an orientation program, we can help alleviate anxieties related to both the new school’s learning environment and its policies and procedures.

Online learning is catching on across disciplines, and we can use it in advising as well. After all, advising is part of the educative process. But what does this mean for educators and advisors? Are we becoming obsolete? I mentioned earlier that students who had completed the tutorial could practically advise themselves—but that does not mean they should.

Technology should not replace educators, but educators can use technology to supplement and enhance what is being taught. Young (2005) says that technology is “not quite ready to replace” educators (p. A31), but I would argue that technology will never be ready for this kind of supplanting. Technology is an aid—it can help us reach a larger audience across time and geographical constraints. Educators need to adapt and grow to use this new learning tool. The very nature of learning dictates that we must keep up with new developments, and this new technology will benefit us by allowing access to students everywhere. Young (2005) says, “This is the future” (p. A31), and with that statement he says it all— technology is here and the future is now.

Resources

Carpenter, T. G., Brown, W. L., & Hickman, R. C. (2004). Influences of online delivery on developmental writing outcomes.

Journal of Developmental Education, 28(1), 14-35.

Gilnett, J. (2006). Seattle Pacific University Visual Identification System. Retrieved February 22, 2006, from http://www.spu.edu/depts/uc/VIS/visual.asp.

Hiltz, S. R., & Turoff, M. (2005). Education goes digital: the evolution of online learning and the revolution in higher education. Communications of the ACM, 48(10), 59-64.

Mudore, C. F. (1999). Your college checklist. Career World, 27(6), 20-22.

Parker, C. E. (1997). Making retention work. Black Issues in Higher Education, 13(26), 120.

Young, J. R. (2005). Virtual tutors guide students but are not quite ready to replace professors. Chronicle of Higher

Education, 52(15), A31.

Special thanks for research and editorial assistance to Mark Hendrickson, Nicholas Jacobson, and Katie Van Loo.

About the Author

Kristen Labrecque is an Undergraduate Academic Counselor at Seattle Pacific University, where she held positions in the

School of Education and in the Admissions Office since 1998 before joining the Student Academic Services team in 2003.

Kristen has been a member of PACRAO since 2004 when she presented information about SPU’s Degree Audit System at the regional conference in Tucson, and has facilitated sessions at the regional conferences in Tucson and Sacramento.

Questions or comments are welcome via e-mail at kristenl@spu.edu.