Capital Budgeting Models

advertisement

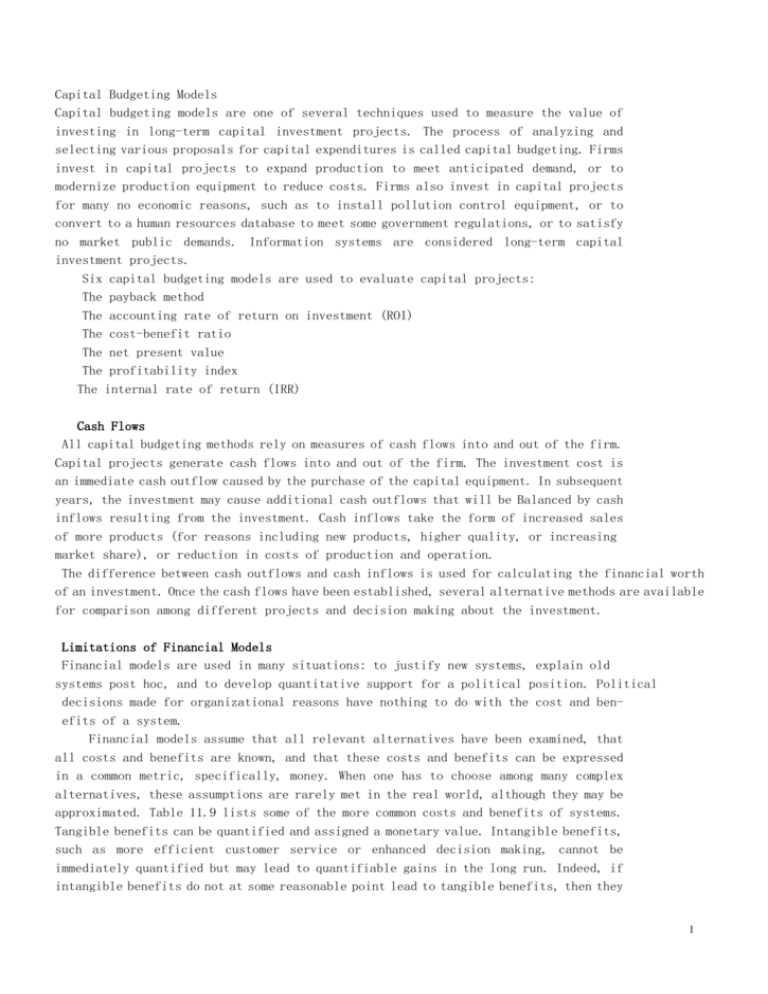

Capital Budgeting Models Capital budgeting models are one of several techniques used to measure the value of investing in long-term capital investment projects. The process of analyzing and selecting various proposals for capital expenditures is called capital budgeting. Firms invest in capital projects to expand production to meet anticipated demand, or to modernize production equipment to reduce costs. Firms also invest in capital projects for many no economic reasons, such as to install pollution control equipment, or to convert to a human resources database to meet some government regulations, or to satisfy no market public demands. Information systems are considered long-term capital investment projects. Six capital budgeting models are used to evaluate capital projects: The payback method The accounting rate of return on investment (ROI) The cost-benefit ratio The net present value The profitability index The internal rate of return (IRR) Cash Flows All capital budgeting methods rely on measures of cash flows into and out of the firm. Capital projects generate cash flows into and out of the firm. The investment cost is an immediate cash outflow caused by the purchase of the capital equipment. In subsequent years, the investment may cause additional cash outflows that will be Balanced by cash inflows resulting from the investment. Cash inflows take the form of increased sales of more products (for reasons including new products, higher quality, or increasing market share), or reduction in costs of production and operation. The difference between cash outflows and cash inflows is used for calculating the financial worth of an investment. Once the cash flows have been established, several alternative methods are available for comparison among different projects and decision making about the investment. Limitations of Financial Models Financial models are used in many situations: to justify new systems, explain old systems post hoc, and to develop quantitative support for a political position. Political decisions made for organizational reasons have nothing to do with the cost and benefits of a system. Financial models assume that all relevant alternatives have been examined, that all costs and benefits are known, and that these costs and benefits can be expressed in a common metric, specifically, money. When one has to choose among many complex alternatives, these assumptions are rarely met in the real world, although they may be approximated. Table 11.9 lists some of the more common costs and benefits of systems. Tangible benefits can be quantified and assigned a monetary value. Intangible benefits, such as more efficient customer service or enhanced decision making, cannot be immediately quantified but may lead to quantifiable gains in the long run. Indeed, if intangible benefits do not at some reasonable point lead to tangible benefits, then they 1 may not be "worth" much. Information Systems as a Capital Project Many well-known problems emerge when financial analysis is applied to information systems (Dos Santos, 1991). Financial models do not express the risks and un- certainty of their own cost and benefits estimates. Costs and benefits do not occur in the same time frame---costs tend to be upfront and tangible, whereas benefits tend to be back loaded and intangible. Inflation may affect costs and benefits differently. Technology--especially information technology---can change during the course of the project, causing estimates to vary greatly. Intangible benefits are difficult to quantify. These factors play havoc with financial models. The difficulties of measuring intangible benefits give financial models an application bias: Transaction and clerical systems that displace labor and save space always produce more measurable, tangible benefits than management information systems, decision-support systems, or computer-supported collaborative work systems Table 11.9 Cost and Benefits of Information System Costs Hardware Benefits Tangible: Cost savings Telecommunications Increased productivity Low operational costs Software Reduced work force Lower computer expenses Services Lower outside vendor costs Lower clerical and professional costs Personnel Reduced rate of growth in expenses Reduced facility costs Intangible: Improved asset utilization Improved resource control Improved organizational planning Increased organizational flexibility More timely information More information increased organizational learning Legal requirements attained Enhanced employee goodwill Increased job satisfaction Improved decision making Improved operations Higher client satisfaction Better corporate image There is some reason to believe that investment in information technology requires special consideration in financial modeling. Capital budgeting historically concerned itself with manufacturing equipment and other long-term investments such as electrical 2 generating facilities and telephone networks. These investments had expected lives of more than one year and up to twenty-five years. Computer-based information systems are similar to other capital investments in that they produce an immediate investment cost, and are expected to produce cash benefits over a term greater than one year. Information systems differ from manufacturing systems in that their expected life is shorter. The very high rate of technological change in computer-based information systems means that most systems are seriously out of date in five to eight years. Although parts of old systems survive as code segments in large programs-- some programs have code that is fifteen to twenty years old--most large-scale systems after five years require significant investment to redesign or rebuild them. The high rate of technological obsolescence in budgeting for systems means simply that the payback period must be shorter, and the rates of return higher than typical capital projects with much longer useful lives. The bottom line with financial models is to use them cautiously and to put the results into a broader context of business analysis. Let us look at an example to see how these problems arise and can be handled. The following case study is based on a real-world scenario, but the names have been changed. Case Example: Primrose, Mendelson, and Hansen Primrose, Mendelson, and Hansen is a 250-person law partnership on Manhattan's West Side. Founded in 1923, Primrose has excelled in corporate, taxation, environmental, and health law. Its litigation department is also well known. The Problem Spread out over three floors of a new building, each of the hundred partners has a secretary. Many partners still have 486 PCs on their desktops but rarely use them except to read the e-mail. Virtually all business is conducted face-to-face in the office, or when partners meet directly with clients on the clients' premises. Most of the law business involves marking up (editing), creating, filing, storing, and sending documents. In addition, the tax, pension, and real estate groups do a considerable amount of spreadsheet work. With overall business off 10 percent since 1995, the chairman, Edward W. Hansen III, is hoping to use information systems to cut costs, enhance service to clients, and bring partner profits back up. First, the firm's income depends on billable hours, and every lawyer is supposed to keep a diary of his or her work for specific clients in 30-minute intervals. Generally, senior lawyers at this firm charge about $500 an hour for their time. Unfortunately, lawyers are not good record keepers; they often forget what they have been working on, and must go back to reconstruct their time diaries. The firm hopes that there will be some automated way of tracking billable hours. Second, much time is spent communicating with clients around the world, with other law firms both in the United States and overseas, and especially with Primrose's branches in Los Angeles, Tokyo, London, and Paris. The fax machine has become the communication medium of choice, generating huge bills and developing lengthy queues. The firm looks forward to using some sort of secure e-mail, perhaps Lotus 3 Notes or even the Internet. Law firms are wary of breaches in the security of confidential client information. Third, Primrose has no client database! A law firm is a collection of fiefdoms each lawyer has his or her own clients and keeps the information about them private. This, however, makes it impossible for management to find out who is a client of the firm, who is working on a deal with whom, and so forth. The firm maintains a billing system, but the information is too difficult to search. What Primrose needs is an integrated client management system that would take care of billing, hourly charges, and making client information available to others in the firm. Even overseas offices want to have information on who is taking care of a particular client in the United States. Fourth, there is no system to track costs. The head of the firm and the department heads who compose the executive committee cannot identify what the costs are, where the money is being spent, who is spending it, and how the firm's resources are being allocated. Perhaps, for instance, health law is declining and the firm should trim associates (nonpartnered lawyers). A decent accounting system that could identifity the cash flows and the costs a bit more clearly than the existing journal would be a big help. The Solution There are many problems at Primrose; information systems could obviously have some survival value and perhaps could grant a strategic advantage to Primrose if a system were correctly built and implemented. We will not go through a detailed systems analysis and design here. Instead, we will sketch the solution that in fact was adopted, showing the detailed costs and estimated benefits. These will prove useful for estimating the overall business value of the new system--both financial and nonfinancial. The technical solution adopted was to create a local area network composed of 100 fully configured Pentium multimedia desktop PCs, three Windows NT file servers, and an Ethernet 10 MBS (megabit per second) local area network on a coaxial cable. Multimedia computers are required because lawyers access a fair amount of information stored on CD-ROM. The network connects all the lawyers and their secretaries into a single integrated system, yet permits each lawyer to configure his or her' desktop with specialized software and hardware. The older 486 machines were given away to charity. All desktop machines were configured with Windows 95 and Office 97 application software, while the file servers ran Windows NT. A networked relational database was installed to handle client accounting and mailing functions. Lotus Notes was chosen as the internal mail system because it provided an easy-to-use interface and good links to external networks (including the internet) and mail systems. Frequently the partners send documents to Paris and San Francisco where the firm maintains satellite offices. The Internet was specifically rejected as an e-mail technology because of its uncertain security. Lotus Notes is still much more versatile than the Web at groupware functions and accounting functions such as simple client management and billing applications. Notes can also incorporate spreadsheets. The Primrose local area network is linked to external networks so that the firm can obtain information on- line from 4 Lexis (a legal database) and several financial database services. The new system required Primrose to hire a chief information officer and director of systems--a new position for most law firms. Four systems personnel were required to operate the system and train lawyers. Outside trainers were also hired for a short period. Figure 11.7 shows the estimated costs and benefits of the system. The system had an actual investment cost of $1,210,500 in the first year (Year 0) and total cost over six years of $3,683,000.'The estimated benefits total $6,075,000 after six years. Was the investment worthwhile? If so, in what sense? There are financial and nonfinancial answers to this question. Let us look at the financial models first. They are depicted in Figure 11.8. The Payback Method The payback method is quite simple: It is a measure of time required to pay back the initial investment of a project. The payback period is computed as Original investment = Number of years to pay back Annual net cash inflow In the case of Primrose, it will take about 2.3 years to pay back the initial investment. (Since cash flows are uneven, annual cash inflows are summed until they equal the original investment in order to arrive at this number.) The payback method is a popular method because of its simplicity and power as an initial screening method. It is especially good for high-risk projects in which the useful life is difficult to know. If a project pays for itself in two years, then it matters less how long after two years the system lasts. The weakness of this measure is its virtues: The method ignores the time value of money, the amount of cash flow after the payback period, the disposal value (usually zero with computer systems), and the profitability of the investment. Accounting Rate of Return on Investment (ROI) Firms make capital investments to earn a satisfactory rate of return. Determining a satisfactory rate of return depends on the cost of borrowing money, but other factors can enter into the equation. Such factors include the historic rates of return expected by the firm. In the long run, the desired rate of return must equal or exceed the cost of capital in the marketplace. Otherwise, no one will lend the firm money. The accounting rate of return on investment (ROI) calculates the-rate of return from an investment by adjusting the cash inflows produced by the investment for depreciation. It gives an approximation of the accounting income earned by the project. To find the ROI, first calculate the average net benefit. The formula for the average net benefit is as follows: (Total benefits-Total cost-Depreciation) = Net benefit Useful life This net benefit is divided by the total initial investment to arrive at ROI(Rate of Return on Investment). The formula is 5 Net benefit = ROI Total initial investment Year 0 1998 1 1999 2 2000 3 2001 4 2002 5 2003 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 3,000.00 500.00 500.00 500.00 500.00 500.00 15,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 1,000.00 150,000.00 50,000,00 50,000.00 50,000.00 50,000.00 50,000.00 50,000.00 15,000.00 10,000.00 50,000.00 15,000.00 15,000.00 2,000.00 3,000.00 15,000.00 2,000.00 3,000.00 15,000.00 15,000.00 2,000.00 2,000.00 3,000.00 3,000.00 15,000.00 15,000.00 2,000.00 3,000.00 50,000.00 22,500.00 50,000.00 10,000.00 50,000.00 10,000.00 50,000.00 50,000.00 10,000.00 10,000.00 50,000.00 10,000.00 100,000.00 240,000.00 100,000.00 100,000.00 100,000.00 100,000.00 100,000.00 240,000.00 240,000.00 240,000.00 240,000.00 240,000.00 120,000.00 1,210,500 491,500.00 491,500.00 506,500.00 491,500.00 491,500.00 Billing enhancements Reduced paralegals Reduced clerical Reduced messenger Reduced telecommunications 350,000.00 50,000.00 50,000.00 15,000.00 10,000.00 400,000.00 100,000.00 100,000.00 30,000.00 10,000.00 Lawyer efficiencies Total Benefits 120,000.00 595000.00 240,000.00 360,000.00 360,000.00 360,000.00 360,000.00 880000.00 1150000.00 1150000.00 1150000.00 1150000.00 Costs: Hardware: File Servers3@20000 60,000.00 PCs 100@3000 300,000.00 Networkcards 10,000.00 100@100 Scanners 6@500 Telecommunications Gateways(网关) 3@5000 Cabling 150000 Telephone connect Costs Software: Database 50000 Network 10000 Groupware 100@500 Windows 100@150 Services: Nexus(连结?) 50,000 Training 300hrs@75/hro CIO 100000 Systems Personnel 4@60000 Trainers 2@60000 Total Costs Benefits: 500,000.00 150,000.00 100,000.00 30,000.00 10,000.00 500,000.00 150,000.00 100,000.00 30,000.00 10,000.00 500,000.00 150,000.00 100,000.00 30,000.00 10,000.00 500,000.00 150,000.00 100,000.00 30,000.00 10,000.00 要求: 1.计算回收期(年) 。 2.计算 ROI 。 全部收益合计 6 3.计算本利率(= ) 全部成本合计 4.用 EXCEL 计算:(贴现率取 5%) (1)净现值 NPV。 (2)获利能力指数(=NPV/投资) 。 (3)内含报酬率 IRR。 7