The Virtual Knowledge Studio for the Humanities and Social

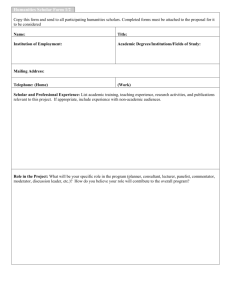

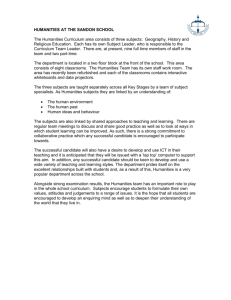

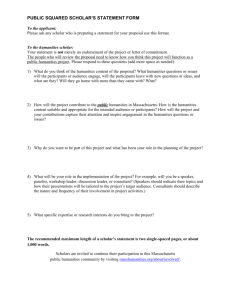

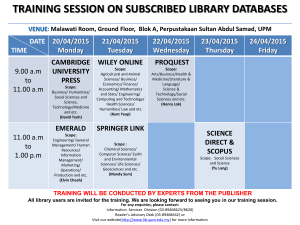

advertisement