Chapter 1: Setting the scene - IOE EPrints

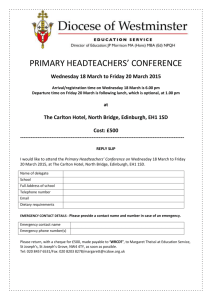

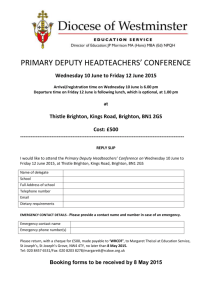

advertisement