Module 6: Job Development and Job Placement

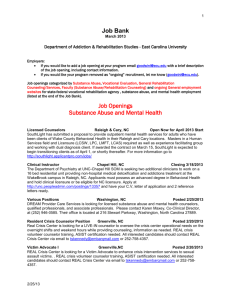

advertisement

Module 6: Job Development and Job Placement “Some people are always grumbling because roses have thorns. I am thankful that thorns have roses.” Alphonse KarrThe job development and job placement processes in vocational rehabilitation begin at the outset of the relationship between counselor and client. Thus, it is correct to say that job placement is ongoing. From this standpoint, when you are first introduced to a new client, you begin orienting them to the purpose of vocational rehabilitation and adjusting the individual to the concept of pursuing work. At this stage, you are engaging the person and they mutually engage you. There is a two-way exchange of ideas, information, emotions and behaviors. This is the adjustment phase of the job placement process that will occur over the first several meetings with a client. You, as a job placement professional, will begin assessing the individual through your observations and record gathering. You may start to notice that the client has a poor handshake, vocal tics or mannerisms that will instantly be off-putting to a prospective employer. At the same time, the individual will be assessing you as a counselor, finding a trust level and impression of vocational rehabilitation services. As the aphorism goes, “first impressions count.” This is not merely a maxim we try to instill in job seekers but in counselors as well, for we are the first impressions clients have to vocational rehabilitation services. Remember, just as an employer scrutinizes an employee for hire, a client is free to scrutinize a public service such as vocational rehabilitation. Once the job development process is under way, a third and possibly fourth party may be engaged in the job placement process, a job developer and, the employer. Based on the considerations that have already been set forth, we must be aware that these new parties will be bringing their own perceptions, work styles and attitudes to the process, creating a new group dynamic. As you become seasoned as a counselor, you will find that specific personality types will be more amenable to one another in pairing clients with both service professionals and employers. Vocational rehabilitation counselors are influenced by personal experiences and their own theoretical stances to the job placement process for an individual with a disability. Though it is not always essential to understand the process of job development to engage and guide a person through employment, it is sometimes helpful to be reminded of the underlying philosophy as to why individuals seek jobs, how they find a job match and how they maintain their careers. Some of the earliest work in this field was done by Frank Parsons, an engineer from Cornell University. Parsons developed the trait and factor theory at the outset of the twentieth century, espousing that an individual brings certain traits to the workforce, and it is the job development professional’s job to survey the individual, survey occupations and find the best match. Though this theory is parsimonious in design, it is one of the most durable and influential career development theories. Today, if you look at most career assessment tools, the guiding principle behind it is Parson’s trait and factor theory. Contemporary job development theories have elaborated upon Parson’s initial framework to include an array of concepts. It remains uncertain if any single theory behind job development reigns supreme as multiple applications have been derived from these ideas, each contributing to some degree in explaining career selection. Some of the notable concepts to emerge in this field are: environmental match (Dawis and Lofquist’s theory of work adjustment), personality styles (Holland’s themes), social learning (Krumboltz’s learning theory, and Mitchell Levin’s and Krumboltz’s happenstance approach theory), cognitive processing (Peterson, Sampson and Reardon), socialcognitive theory (Lent, Brown and Hackett), compromise theory (Gottfredson), personin-environment theory (Bronfrenbrenner) and contextualism (Young, Valach and Collin). While most of these theories acknowledge each other’s relevance, they place a different emphasis on the approach to working with a job seeker. For instance, while Parson’s model lends itself to the use of assessment and diagnosis data in career counseling, social learning models lend themselves to counseling approaches that use coaching, mentoring and cognitive restructuring techniques. It is not to say that one career development model is better than another, or that they are mutually exclusive. Many of these theories remain untested in practice, not to mention that even fewer have been validated for individuals with disabilities and for minority populations. However, it is important to know that there are a variety of approaches and frameworks from which any one counselor and client pair can operate. Over time it is becoming more evident that a flexible, eclectic approach is necessary to work with the diversified population seeking vocational rehabilitation services. One notable theory that encompasses a holistic perspective, and that continues to be developed with empirical support is Donald Super’s theory of career development. Super’s theory is developmentally grounded, insofar that he posited a person moves through specific stages in the evolution of their work identity across the entire lifespan. In Super’s original description of this process, he sequenced five stages individuals move through as they develop a work self-concept. The first stage is crystallization occurring between the ages of 14 and 18. It is within this period that a person begins to form a basic vocational goal for him or herself, typically based upon what they have been exposed to. From ages 18-21 individuals move into the specification phase with their vocational goals shifting from being exploratory and uncertain to concrete and specific. The implementation phase follows generally between the ages of 21 and 24. Within this stage, a person often completes training and is entering employment. The two stages that follow, stabilization and consolidation, occur from the mid twenties on, with individuals confirming their chosen professions or changing positions based upon their goals or advancing within their chosen field. In the early formulation of this theory, Super’s stages were sequential and linear. Over the past twenty years, this formula has been researched and modified based upon the discoveries that people rarely move through these stages sequentially, often recycling and skipping stages. This is true especially with individuals with disabilities, some of whom may not have experienced traditional developmental milestones, thus being delayed or possessing deficits in their understanding of themselves in relation to vocational prospects. The most advanced vocational model that Super and his colleagues have proposed is the archway model. This theory was proposed as a life-span-life-space approach to career development as it incorporates individual factors (self concepts, developmental stages), biological factors (needs, values, personality, interests), psychological factors (intelligence, aptitudes, achievement), geographical factors (school, family peer groups, community) and societal factors (economy, labor market, employment practices, social policy). Super further proposed that each of these factors had varying interaction effects with every other factor, which in turn facilitated interactive learning. As you can see, this theory touches on most of the holistic factors we are dealing with in career counseling, though we will best serve our purposes by focusing on the most salient aspects when working with each client. For example, Super’s theory can be utilized in practice by ensuring that intake and assessment documentation covers most of the personal, psychological, biological and social factors previously described. In addition, work values have been determined to be an integral part of successful job placement. Thus, work values inventories are an effective adjunct tool in career counseling. Most importantly, once data and assessment data is compiled and summarized, Super emphasized that the information be interpreted with the client. This provides the client with the assurance that the counselor understands their life story and perspective on employment, serving as the basis for a healthy, productive counseling relationship. Once the theoretical base has been established for job development, practical considerations are primary. This entails a move from the data gathering and assessment phases to the planning and implementation phases toward job attainment. Some of the essential components of this phase are: translating the individual’s story into a strengths based proposal for employment, analyzing the local job market for opportunities, teaching the person to job develop themselves (interviewing skills, modeling, rehearsing, resume development, job club), and preparing for employer concerns and considerations. This again, is a difficult and complex process. However, with a sound therapeutic alliance with the client and some practiced methods, one can easily become a successful job developer and promoter of their clients. For example, you may consider drafting an employment proposal template such as this: Hello, My name is Gregor Samsa and I am a career counselor at the Delaware Department of Labor. I work with young adults exiting high school, and with those who have recently exited that are pursuing training or college in assisting them in obtaining jobs. I noticed your job posting at Delaware Technical and Community College for servers and back house staff and was wondering if you had positions still available? If so, I'd be happy to provide you with some additional information and resumes on several prescreened/qualified candidates. Regards, Gregor Samsa Career Counselor For other concrete suggestions, it is recommended that you use a copy of Denise Bissonette’s textbook Beyond Traditional Job Development. Bisonnette outlines specific approaches to job development, responding to employer concerns, identifying new market opportunities and understanding different employer personalities, in addition to other highly effective resources. It is essential to keep in mind that the greatest obstacles in employing an individual with a disability are the attitudes of employers and environmental barriers. When it comes to these matters, rehabilitation professionals need to be aware of the facts related to employment of persons with disabilities. The truth is that studies on this subject find that persons with disabilities rate equal or better in terms of safety, productivity and overall performance when compared to individuals without disabilities in their jobs (Dupont, 1981, 1990). A study by Noel (1990) indicated that businesses that employed persons with disabilities, when compared to businesses that did not, had no differences in terms of their workers compensation rate premiums and no difference in their safety records. An additional concern that many employers have is the expense of accommodations. When it comes to this matter, studies have shown that less than 25% of employees with disabilities require an accommodation on the job. Within the group that does require accommodations, many cost nothing (extra breaks, reorganization of job tasks). Further, a survey of U.S. employers indicated that 50% of workplace modifications cost less than $50; 20% cost $51-$500; 17% cost $501-$1000; and a mere 13% cost more than $1000 (Jones, 1993). It is clear that there is little risk in employing an individual with a disability. George Eastman the founder of Kodak, stated, “Kodak doesn’t sell pictures, we sell memories.” We must remember we are not selling a commodity. We do not sell custodians, engineers, nurses or restaurant workers to employers. We do not sell cogs for machines. We are selling opportunities and dealing with the value of human lives. It is an exchange with vast opportunity. There is an opportunity of improving an employer’s human resource capital and of diversifying their workforce. There are the employee’s opportunities of achieving greater meaning and value in their lives, of self-sufficiency and freedom, of equality. Last but not least, there is the opportunity for the job development professional, to be part of an important social movement, to develop their own meaning through work and to be valued through their company and by the people they represent. Select Reading: Counseling American Minorities by Donald R. Atkinson Beyond Traditional Job Development by Denise Bissonnette